BACKGROUND

The expectations of employees toward their employers are undergoing a transformation. Currently, especially younger employees entering the labor market anticipate actions aimed at fostering a workplace climate conducive to equality, diversity, and a sense of belonging. Values such as partnership and respectful treatment have become fundamental to employee satisfaction and engagement (ManpowerGroup, 2023, 2024). Furthermore, nearly half of the workforce reports engaging in overwork almost daily, attributing stress and fatigue to negative perceptions of organizational pressures and the reinforcement of overperformance norms. This often involves working beyond regular hours and sacrificing personal plans or activities to achieve higher professional outcomes (ManpowerGroup, 2023).

Despite employees more openly communicating their needs – particularly with a focus on social relationships within organizations – there is a scarcity of research examining how meeting these expectations correlates with key job attitudes and organizational behaviors. This study addresses this gap by introducing and empirically testing the concepts of communal and agentic workplace climates. A communal workplace climate (CWC) refers to an environment in which organizational and managerial priorities center on fostering positive, respectful relationships among employees. In contrast, an agentic workplace climate (AWC) emphasizes individual performance, productivity, and the achievement of ambitious goals (Jurek & Olech, 2024).

The unique contribution of this study lies in its integration of theoretical models from social, organizational, and motivational psychology (i.e., the Stereotype Content Model, Self-Determination Theory, the Job Demands-Resources model, and Affective Events Theory), with an empirical exploration of both the “bright” and “dark” sides of workplace climates. While previous research has demonstrated the general impact of workplace climate on employee organizational behavior (Ashkanasy & Härtel, 2014; Ehrhart & Raver, 2014), the current study advances the literature in three important ways: (1) differentiation between communal and agentic workplace climates. Although conceptually related to constructs such as relational or performance-oriented climate, we empirically distinguish these two climate types and explore their differential associations with both positive (work engagement) and negative (burnout) outcomes; (2) emotion-based mediation mechanisms. Drawing on Affective Events Theory, we investigate how employees’ emotional attitudes toward the organization mediate the relationship between perceived workplace climate and job attitudes – offering a process-based explanation of these effects; (3) contextual contribution. By focusing on employees from various industries in Poland, this study provides culturally contextualized evidence that enriches the broader literature, which has often been dominated by Anglo-American samples.

COMMUNAL AND AGENTIC WORKPLACE CLIMATES

People need to make sense of the complex environments they live in by trying to understand and anticipate the behavior of others. According to the Dual Perspective Model (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014), most human actions can be perceived from two distinct perspectives – that of the agent and that of the recipient. The agent perspective focuses on agentic content such as goal completion, while the recipient’s point of view is dominated by communal aspects like social relationships. Agency (competence) and communion (warmth) are two fundamental dimensions of social cognition that influence how we perceive other individuals and social groups (Cuddy et al., 2007).

These two types of attributes ascribed to leaders and coworkers determine their acceptance (Chemers, 2001). Similarly, the perception of teams and organizations may be influenced by these dimensions. Groups characterized by high agency are often seen as competitive, individualistic, and goal-oriented. Conversely, communion refers to perceiving a group as warm, supportive, and cooperative, reflecting interdependence and concern for others’ welfare. Associating a group with high agency and low communion often triggers negative stereotypes associated with power and selfishness. Conversely, viewing a group as high in communion and low in agency is associated with positive stereotypes, reflecting care and support (Cuddy et al., 2007). Abele and Wojciszke (2019) point out that agency benefits the agent themselves, as it indicates effectiveness in pursuing one’s own interests and achieving set goals, whereas communion benefits others, as it focuses on caring for others’ well-being and fostering social relationships.

In various theoretical models, agency-related contents can be found in dimensions such as individualism, task orientation, and competence, while communion is associated with collectivism, relationship orientation, and warmth (Abele & Wojciszke, 2019). In the organizational context, these two dimensions are primarily evident in leadership behaviors within organizations. Fiedler’s Contingency Model (Fiedler, 1967) is one framework that describes task-oriented and relationship-oriented leadership styles, significantly impacting workplace climate and employee attitudes and behaviors (Behrendt et al., 2017; Yukl, 2012). Task-oriented leaders prioritize task completion, while relationship-oriented leaders emphasize interpersonal connections.

Organizations are complex systems in which having ambitious individual goals and building satisfying interpersonal relationships are equally relevant. These two aspects have proven to be relevant for many work processes (Gartzia, 2022). Effective job performance is therefore based on two fundamental modalities: agency and communion. Agency in this context refers to an individual’s attempts to master the environment and experience competence, while communion refers to a person’s need to closely relate to and cooperate with others (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014).

Organizational climate refers to employees’ shared perceptions of their work environment, encompassing the norms, values, and behaviors encouraged and rewarded within the organization (Schneider & Barbera, 2014). By definition, it is a group-level phenomenon, represented by aggregated views that embody a team’s or an entire organization’s shared sentiments (Yammarino & Dansereau, 2011). However, researchers often analyze workplace climate through the lens of individual-level perceptions, shaped by personal experiences. James et al. (1988) defined individual-level workplace climate as psychological climate – an individual’s perception of their work environment, emphasizing the subjective evaluation of organizational features and their relevance to personal well-being and functioning. Specifically, they conceptualized it as the meaning individuals attach to their work environment based on how they perceive and interpret organizational structures, processes, and policies, particularly concerning their own goals, values, and needs. Given that the same measures can, depending on study design, collect data for multilevel analyses as well as individual-level evaluations, we propose using the more universal term workplace climate to encompass both levels of analysis.

Observable organizational practices, including evaluation criteria, promotion structures, job expectations, and decision-making processes, serve as manifestations of both dimensions of workplace climate. A communal workplace climate reflects employees’ perceptions of policies and practices that nurture interpersonal relationships and foster a sense of community within their work. A communal climate typically emphasizes caring for people and cultivating long-term, positive relationships; encourages people-oriented leadership; values harmony and mutual agreement among team members; and promotes values such as loyalty and trust. In such settings, employees are appreciated for their involvement in internal organizational matters, and the organization’s success is measured by employee development and the strengthening of commitment. In contrast, agentic workplace climate pertains to employees’ perceptions of policies and practices aimed at optimizing efficiency and performance. Such a climate prioritizes job results and individual achievement; promotes performance-oriented leadership; sets ambitious goals and challenges; and values competition and winning. Employees are primarily appreciated for goal achievement, and success is defined as outperforming competitors and attaining market leadership.

In terms of organizational perception, attention has been drawn to these two dimensions in the GLOBE cultural framework (House et al., 2004). Performance orientation and relational orientation are dimensions that reflect an organization’s emphasis on valuing and rewarding performance and achievement (performance orientation) or prioritizing positive relationships with organization members (relational orientation). Highly performance-oriented organizations often set ambitious goals, prioritize competition, recognize outstanding results, and emphasize individual accountability. While fostering high productivity and a competitive edge, overemphasis on performance may lead to overload. Conversely, highly relational-oriented organizations engage employees, encourage open communication, and nurture a positive work climate. This emphasis fosters employee attachment, loyalty, and engagement.

The impact of employees’ perception of workplace climate is significant, influencing their well-being, job satisfaction, and overall behaviors, whether productive or counterproductive (Ashkanasy & Härtel, 2014; Ehrhart & Raver, 2014). Previous studies have suggested that the relational climate, conceptually linked to the communal workplace climate, exhibits positive correlations with procedural justice, perceived organizational support, and affective organizational commitment (Boyatzis & Rochford, 2020). In contrast, a highly performance-oriented climate (House et al., 2004), which aligns with an organization’s emphasis on valuing and rewarding performance and achievement (conceptually associated with an agentic workplace climate), is characterized by the setting of ambitious goals, prioritizing competition, recognizing outstanding results, and emphasizing individual accountability. This orientation may foster heightened motivation, increased productivity, and a competitive edge.

However, an extreme agentic workplace climate may lead to adverse consequences for attitudes and behaviors within an organization. For example, Berdahl et al. (2018) introduced the concept of a masculinity contest culture, characterized by dominance, avoidance of vulnerability, and the promotion of ruthless competition. This culture, conceptually linked to an agentic workplace climate, correlates with detrimental outcomes such as toxic leadership, dominant coworker behaviors, burnout, turnover intentions, and reduced personal well-being.

WORK ENGAGEMENT AND OCCUPATIONAL BURNOUT

Work engagement and occupational burnout are two opposing yet independent states that individuals may experience in the workplace. Work engagement is defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2010). It involves exerting effort and striving for optimal job performance (Saks, 2006). On the other hand, job burnout is marked by feelings of energy depletion, exhaustion, and increased mental distance from one’s job (World Health Organization, 2022). The independence of these two states lies in the fact that a low level of work engagement does not necessarily imply burnout, and the absence of occupational burnout does not indicate engagement. For decades, both phenomena have been extensively studied by work and organizational psychologists, earning recognition as perhaps the most crucial constructs describing employees’ attitudes and behaviors in organizations.

Work engagement is a positively desirable state associated with job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and the intention to stay within the organization (Christian et al., 2011). It develops through positive workplace experiences and satisfying working conditions that include autonomy, opportunities for professional development, supportive social relationships, recognition and reward, as well as interesting and meaningful tasks (Mazzetti et al., 2023). Employees are more likely to engage and generate positive outcomes in a supportive environment, as a positive organizational climate sustains employee motivation. It can be achieved through creating a work environment that’s psychologically safe, where employees can be themselves and speak openly also by being involved in the process of designing their own roles and meeting the company goals (Rogg et al., 2001).

In contrast to work engagement, job burnout is an undesirable state negatively associated with job performance (Corbeanu et al., 2023) and detrimental to employees’ health (World Health Organization, 2022). It results from chronic workplace stress that has not been effectively managed (Maslach et al., 2001). The primary foundation for the development of occupational burnout syndrome is the employee’s confrontation with job duties and broader work demands that they cannot meet. This occurs, for instance, when there is an excessive workload or when the tasks are too challenging, and the pressure to achieve results is immense (de Beer et al., 2016). Poorly designed work, characterized by unclear role expectations, team conflicts, ineffective leadership, and ultimately a negative workplace climate, is also a contributing factor to job burnout (Leiter & Maslach, 2003). Leiter and Maslach (2003) introduced the Six Areas of Worklife Model which suggests that burnout may stem from a chronic mismatch between employee’s expectations and their actual work setting as far as the following six areas are concerned: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values. This approach highlights the importance of looking at workers in a broader context, rather than just looking at individual or situational conditions (Maslach et al., 2001).

The commonly used theory to explain the causes and consequences of burnout is the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), which proposes that working conditions can be divided into two broad categories: job demands and job resources. This perspective assumes that burnout occurs as a consequence of imbalance between the demands and resources derived from work. It is plausible that perceiving the workplace as communal serves as a source of resources, addresses fundamental psychological needs, provides support, and fosters a positive attitude towards work and the organization. On the other hand, an agentic workplace climate is designed to be cultivated in organizations to either sustain or increase productivity. Its objective is to enhance employee engagement by recognizing efficient task execution, reinforcing exceptional achievements, and focusing on established goals.

CURRENT STUDIES: HYPOTHESIS FORMULATION

Considering the factors mentioned above, we hypothesized that both communal and agentic workplace climates are related to employee work engagement and job burnout. Drawing from the Stereotype Content Model (Cuddy et al., 2007), one can anticipate that perceiving the organization in terms of communality (warmth) and agency (competence) categories elicits emotional and behavioral consequences. Employees who perceive their workplace as communal identify it with a group that acts in their interest, is friendly and trustworthy, and where they expect to be treated with respect. Consequently, such organizations evoke positive emotions among their members and motivate them to act in favor of the organization. Taking these considerations into account, we formulated the hypothesis that the more employees perceive their workplace as communal, the more they engage in work (hypothesis 1).

A communal workplace climate is considered a resource within the framework of the JD-R model, according to which resources are factors that reduce the costs associated with coping with work demands and, by meeting employees’ needs, support development and help achieve professional goals (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). A communal workplace climate, due to its association with trust among coworkers, experiencing support, and being treated well by the organization, may satisfy the need for relatedness, which is not only one of the foundations of employees’ intrinsic motivation development but also serves as a buffer in coping with difficulties (Ryan & Deci, 2018). Taking these considerations into account, we expected that the more employees perceive their workplace as communal, the less they experience burnout (hypothesis 2).

Referring to the Stereotype Content Model (Cuddy et al., 2007), perceiving the organization as agentic (competent) may evoke admiration among employees and motivate them to act in its favor, provided that this perception is accompanied by recognition of the organization as communal, meaning that it cares about employees’ interests. However, when assessing the organization as non-communal, its agentic nature may evoke negative emotions, which in turn may incline employees towards passive actions detrimental to the organization. Referring to the Self-Determination Theory, the need for competence is one of the three basic psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, 2018). Identifying with a highly agentic organization may serve to satisfy this need among employees. Accordingly, we formulated the hypothesis that the more employees perceive their workplace as agentic, the more they engage in work (hypothesis 3).

However, given that a highly performance-oriented climate may be associated with work overload and outcome pressure exerted on employees, we also hypothesized that the more employees perceive their workplace as agentic, the more likely they are to report experiencing burnout (hypothesis 4). In this context, the agentic nature of the organization may serve as a source of adverse working conditions, which, according to the JD-R model, are associated with effort and psychophysiological costs incurred by the employee. Therefore, we expect that employees who perceive their workplace as highly agentic may be more susceptible to experiencing burnout due to the demanding nature of the work environment.

In our adopted theoretical framework, we also posit that experiencing communal and agentic workplace climates influences both positive and negative emotions. These emotions, in turn, affect the development of work engagement and the occurrence of burnout syndrome. Our mediating hypotheses are based on Affective Events Theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996), which explains how emotions impact job attitudes and organizational behaviors. Research indicates that positive events can buffer the effects of negative or stressful situations, particularly when the nature of these events is similar (Ohly & Schmitt, 2015). For instance, positive events that build communion values might enhance resources that protect against the effects of negative situations threatening these same values. Therefore, distinguishing between communion-oriented and agency-oriented positive events is crucial for understanding the conditions under which positive events enhance well-being and prevent fatigue. Within this framework, we hypothesize that the relationship between communal workplace climate and work engagement is mediated by a positive emotional attitude toward the organization (hypothesis 5). This is based on the premise that employees who perceive their organization as caring for people, creating conditions for developing a sense of belonging, and satisfying basic psychological needs (i.e., relatedness) are more likely to be engaged in their work, as they feel valued, supported, and beneficiaries of organizational success. Moreover, the negative association between communal workplace climate and job burnout is postulated to be mediated by a negative emotional attitude toward the organization, given its negative correlation with communal workplace climate (hypothesis 6). In this case, employees who hold negative perceptions of their organization, viewing it as less supportive, ignoring people’s needs, and treating employees disrespectfully in an instrumental manner, may experience feelings of cynicism, frustration, and detachment towards the organization, contributing to burnout.

We also propose that the relationship between an agentic workplace climate and work engagement is mediated by a positive attitude toward the organization (hypothesis 7), based on the premise that employees who perceive their organization as competent, efficient, well-organized, and highly successful in achieving goals are more likely to be engaged in their work, as they feel proud and motivated to contribute to organizational goals. Conversely, the link between an agentic workplace climate and job burnout is hypothesized to be mediated by negative attitudes toward the organization (hypothesis 8). In this case, the dark side of an agentic workplace climate is considered, which may be associated with pressure to achieve results and enforcing discrepancies between plans and outcomes, undoubtedly leading to negative experiences for employees. In this context, an agentic workplace climate may lead to a negative attitude towards the organization, and further, to burnout.

By exploring these mediating pathways, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of how workplace climates affect employees’ emotional experiences, attitudes toward the organization, and ultimately, their work-related attitudes. These hypotheses provide a theoretical framework for examining the complex interplay between workplace climates, attitudes, and employee well-being, which has practical implications for organizational interventions aimed at promoting positive work environments and reducing burnout.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

To test the hypotheses, we conducted two cross-sectional studies comprising a total sample of 910 participants. Each study utilized distinct methods for measuring burnout and work engagement. In Study 1, involving 336 employees from various organizations, we investigated the association between the perception of the workplace as communal and agentic and four core symptoms of occupational burnout –exhaustion, cognitive impairment, emotional impairment, and mental distance – alongside work engagement. Study 2, with the participation of 574 employees, replicated Study 1 but employed different measurement tools to assess job burnout and work engagement. Furthermore, we explored the role of positive and negative attitudes toward the organization as potential mediators in the relationships between workplace climate and job burnout/work engagement.

PROCEDURE

The studies were conducted using a research platform that allowed participants to complete the survey on both computers and mobile devices (smartphones, tablets). Participants received an electronic survey link directly from the research assistants. The study protocol was designed in accordance with the American Psychological Association’s ethical guidelines for scientific research. The research was conducted following ethical approval from the Ethics Committee at the University of Gdansk (Approval No. 07/2024/WNS). Participants were informed about the full anonymity and voluntary nature of their participation, assuring them that they could withdraw at any point, with even partial responses being removed from the database. Only adult individuals actively employed in their current position and within their current organization for a minimum of six months were eligible to participate in the studies. Table 1 provides a characterization of participants in the two conducted studies.

Table 1

Demographic composition of participants in Study 1 and Study 2

MEASURES

In both studies, standardized psychometric tools were utilized to assess the main variables. Additionally, the survey included demographic questions related to age, gender, education, work tenure, current position, job area, and organization size.

The Communal and Agentic Workplace Climate Scale (Jurek & Olech, 2024) was used in Study 1 and Study 2. This tool consists of 12 statements (6 for each dimension) describing practices and principles prevailing in the organization concerning communal (e.g., “In the organization where I work, caring for people and maintaining lasting and good relationships are paramount”) or agentic (e.g., “In the organization where I work, results and the best task performance are the most important”) workplace climates. Respondents are required to rate each statement on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The 9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9; Schaufeli et al., 2006), implemented in Study 1, is a widely used instrument designed to assess work engagement among individuals. It focuses on three key dimensions: vigor (e.g., “At my work, I feel bursting with energy”), dedication (e.g., “I am enthusiastic about my job”), and absorption (e.g., “I am immersed in my work”). Respondents rate their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always/every day). The scale is employed to measure the positive, fulfilling aspects of work experiences, reflecting an individual’s energy, dedication, and immersion in their tasks.

The Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT; Schaufeli et al., 2019) was used in Study 1. This tool, in its abbreviated form (Hadžibajramović et al., 2022), consists of three items assessing each burnout core symptom: exhaustion (e.g., “At work, I feel mentally exhausted”), cognitive impairment (e.g., “At work, I have trouble staying focused”), emotional impairment (e.g., “At work, I feel unable to control my emotions”), and mental distance (e.g., “I feel a strong aversion towards my job”).

The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti & Bakker, 2008) was implemented in Study 2. Originally consisting of 16 items with a 4-point response scale, a modified version with a 5-point response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was employed in the research. The questionnaire was designed to measure two subscales: burnout and lack of work engagement. However, subsequent research findings justified distinguishing four factors: the first two (exhaustion, e.g., “There are days when I feel tired before I arrive at work”, and distancing from work, e.g., “Lately, I tend to think less at work and do my job almost mechanically”) were treated as measures of job burnout, while the latter two (vigor, e.g., “When I work, I usually feel energized”, and interest in work, e.g., “I always find new and interesting aspects in my work”) served as measures of work engagement.

The PNE Scale, implemented in Study 2, measures positive and negative emotional affective attitudes towards organization, consisting of 12 statements (Jurek & Olech, 2019). For each statement (e.g., “I feel proud to work for my organization” – positive attitude; “When I’m at my workplace, I only dream of leaving it” – negative attitude), respondents are required to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale (1 – strongly disagree; 5 – strongly agree) the extent to which they agree with the given statement.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

In Study 1, the collected data underwent multiple regression models, using communal workplace climate and agentic workplace climate as predictors and measuring work engagement and occupational burnout as dependent variables. Essential demographic variables, including gender, age, managerial vs. non-managerial position, and tenure in the current position, were treated as controlled variables in these models.

Study 2 employed a path model to assess the formulated hypotheses, concurrently investigating the associations between communal and agentic workplace climates with work engagement and job burnout. The analysis also took into account the mediating role of positive and negative attitudes toward the organization. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R environment (R Core Team, 2024).

RESULTS

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for the variables measured in Study 1, along with reliability estimates computed using Cronbach’s α coefficients (all coefficients indicate good reliability; α < .70). As shown in Table 2, employees’ perception of the workplace as communal significantly and positively correlates with their engagement and negatively with job burnout. Additionally, it is demonstrated that an agentic workplace climate significantly, albeit weakly, correlates positively with work engagement but not with job burnout.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, and Cronbach’s α coefficients for examined variables in Study 1

To examine the extent to which communal and agentic workplace climates predict work engagement and job burnout while controlling for basic socio-demographic variables (gender, age, managerial role, and tenure in the current position), two multiple regression models were fitted (one for each dependent variable). The results of fitting these models are presented in Table 3. As shown, the results indicate that higher engagement is reported by older employees working in managerial positions. In line with expectations, employees who perceive their workplace as more communal reported higher levels of work engagement. Additionally, in line with expectations, communal workplace climates proved to be robust negative predictors of job burnout—the more communal the workplace is perceived, the lower the intensity of burnout symptoms. These findings supported hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2. An agentic workplace climate did not emerge as a significant predictor of work engagement when socio-demographic variables were included in the model (hypothesis 3 was not supported). Only a weak positive correlation with job burnout was observed, providing support for hypothesis 4.

Table 3

Regression results investigating how communal and agentic workplace climates predict work engagement and job burnout in Study 1

In Table 4, descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the main variables measured in Study 2 are presented. The table also incorporates internal consistency coefficients as reliability indicators. As observed, a communal workplace climate positively and strongly correlates with work engagement (supporting hypothesis 1) and a positive attitude toward the organization. In contrast, it moderately negatively correlates with job burnout (supporting hypothesis 2) and a negative attitude toward the organization. Agentic workplace climate significantly correlates positively, albeit weakly, with job burnout (supporting hypothesis 4). However, no significant association was found between this climate and positive organizational attitudes or work engagement; thus, hypothesis 3 was not supported. Regarding organizational attitudes, work engagement, and job burnout, strong correlations, consistent with the expected direction, were obtained, similar to previous studies.

Table 4

Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, and Cronbach’s α coefficients for examined variables in Study 2

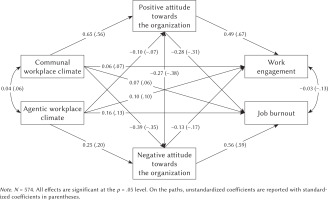

To capture more nuanced relationships between the variables under investigation, a path model was fitted demonstrating how communal and agentic workplace climates predict work engagement and burnout. In this model, it was assumed that positive and negative attitudes toward the organization mediate these relationships in such a way that the experience of communal workplace climate is associated with a positive attitude toward the organization, which in turn positively relates to work engagement and negatively to job burnout. The model also tested the path from agentic workplace climate through negative attitude toward the organization to job burnout. Figure 1 illustrates the outcomes of the path analysis. As interpreted from the figure, communal workplace climate indirectly enhances work engagement (indirect effect = 0.32, β = .38, p < .001) through a positive attitude toward the organization and, indirectly, mitigates burnout (indirect effect = –0.22, β = –.20, p < .001) by reducing a negative attitude toward the organization. Hence, the results obtained from Study 2 corroborated hypotheses 5 and 6.

Figure 1

Path model testing how communal and agentic workplace climates predict burnout and work engagement based on Study 2 data

A precisely opposite mechanism can be observed for agentic workplace climate: since it positively correlates with negative attitude toward the organization, it indirectly increases the risk of burnout (indirect effect = 0.13, β = .11, p < .001), thus supporting hypothesis 8. Conversely, as it negatively correlates with positive organizational attitude, it indirectly diminishes work engagement (indirect effect = –0.05, β = –.05, p = .044), indicating a result contrary to what was assumed in hypothesis 7. It is noteworthy that the tested mediation effects for communal workplace climate were considerably stronger compared to the effects observed for agentic workplace climate.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the two studies was to investigate the predictive role of communal workplace climate and agentic workplace climate in relation to work engagement and occupational burnout. Employing distinct measures for work engagement and job burnout, along with diverse statistical approaches, it was observed that the more employees perceive their workplace as communal, the more they report higher work engagement and a lower level of job burnout. This relationship is attributed to the fact that a communal workplace climate is associated with a stronger experience of positive attitudes toward the organization and a weaker experience of negative attitudes.

The findings concerning agentic workplace climate were considerably weaker and more complex. On one hand, agentic workplace climate indirectly heightens the risk of job burnout and decreases work engagement by impacting employees’ emotional attitudes toward the organization – positively correlating with negative attitudes and negatively correlating with positive attitudes. However, the association between agentic workplace climate and job burnout was marginal in Study 1. Furthermore, although agentic workplace climate showed a weak positive correlation with work engagement, this relationship did not remain significant when controlling for key socio-demographic variables.

THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS

The findings underscore the role of a communal workplace climate in fostering work engagement through a positive attitude toward the organization, while simultaneously acting as a protective factor against job burnout by mitigating negative attitudes. A communal workplace climate, characterized by its emphasis on community, collaboration, and shared values among employees, manifests in interactions, support, and collective contributions, creating a positive and cohesive work environment. Open communication, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to common goals foster a sense of belonging, trust, and cooperation among team members. This atmosphere supports employee well-being, promoting strong engagement and reducing burnout, highlighting its significance for individual and organizational productivity.

The study aligns with the concept of relational climate proposed by Mossholder and colleagues, emphasizing the critical role of employees’ subjective experiences with human resource (HR) policies and practices that impact interpersonal relationships within individuals, teams, or organizations (Mossholder et al., 2011). Boyatzis and Rochford’s (2020) research further supports these findings, indicating that a workplace climate focused on high-quality relationships positively correlates with affective organizational commitment. Additionally, a relational climate protects against group ostracism (Christensen-Salem et al., 2021), and team members in a high communal sharing climate are less likely to conceal knowledge (Banagou et al., 2021; Batistič & Poell, 2022).

The present study also aligns with the concept of positive workplace relational systems introduced by Kahn (1998). Relational systems provide a theoretical perspective emphasizing workplace relationships as a fundamental factor in organizational life. These relationships play a crucial role in shaping employees’ work-related behaviors and attitudes. Researchers concur that fostering positive relationships in the workplace enhances employees’ work engagement, improves psychological health, enhances team coordination, and helps organizations navigate crises (Byrne et al., 2017; Ehrhardt & Ragins, 2018; Fiaz & Muhammad Fahim, 2023).

In summary, the current study contributes to the broader understanding that a work environment prioritizing valuable social relationships and employee well-being plays a significant role in building engagement and achieving common goals. The communal workplace climate emerges as a key factor in shaping positive work-related attitudes and behaviors.

In contrast to the communal workplace climate, the agentic workplace climate shows weaker but noteworthy associations. It demonstrates limited or no direct connections with a positive attitude toward the organization or with work engagement and exhibits only a marginal positive correlation with negative job attitudes. Specifically, the agentic workplace climate indirectly increases the risk of burnout and decreases work engagement by affecting emotional attitudes – strengthening negative and weakening positive emotional responses toward the organization. These results are partially consistent with the concept of a “masculinity contest culture” introduced by Berdahl et al. (2018). This extreme form of competitive culture is characterized by dominance, suppression of vulnerability, and ruthless internal competition, and is associated with toxic leadership, burnout, and reduced well-being.

It is crucial to emphasize, however, that the construct of agentic workplace climate – as used in this study – does not reflect these extreme characteristics. Rather, it refers to an environment in which individual achievement, goal-orientation, and personal initiative are emphasized. In such contexts, healthy competition for recognition and promotions is encouraged, and employees are expected to take ownership of their responsibilities while demonstrating problem-solving skills. Thus, while the masculinity contest culture can be viewed as a distorted and extreme form of agency, the agentic workplace climate as defined here may have both constructive and detrimental implications depending on contextual factors.

This nuanced pattern of findings is consistent with theoretical models such as the Stereotype Content Model (Cuddy et al., 2007), which suggests that perceiving an organization as competent (agentic) can lead to admiration and motivation to contribute – but only when it is also perceived as communal. Without communality, competence may evoke distrust or aversion. Moreover, according to Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2018), agency can fulfill employees’ need for competence, enhancing motivation and engagement. However, when agency is accompanied by performance pressure and lack of interpersonal support, it may create strain, leading to burnout. This duality may explain why the indirect paths from agentic climate to engagement and burnout in this study are weaker and more conditional than those for the communal climate. The results of the path analysis from Study 2 support this interpretation. Communal workplace climate indirectly enhanced work engagement through a positive attitude toward the organization and indirectly mitigated burnout via a reduction in negative attitudes. Conversely, agentic workplace climate was found to indirectly increase the risk of burnout and to slightly diminish work engagement.

This pattern underscores the importance of balancing agentic elements with communal values in workplace climate. When employees can pursue goals while also feeling respected, supported, and socially connected, the organization reaps the benefits of both motivation and well-being. As Ryan and Deci (2018) argue, people thrive when both competence and relatedness needs are met. Similarly, Bakker and Oerlemans (2019) note that work engagement is most strongly experienced when individuals achieve personal goals in environments enriched by close interpersonal relationships. Therefore, organizations should aim to create structural opportunities to support both agency and communion in daily work life to protect engagement and sustain high performance.

LIMITATIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH

This cross-sectional study comes with several limitations that should be considered in interpreting the findings and outlining directions for future research. First and foremost, the nature of this research design restricts our ability to establish causal relationships. Although this study provides valuable insights into the associations between communal and agentic workplace climates, longitudinal and experimental designs, including interventions in randomized samples, would be advantageous for drawing more robust causal inferences.

Additionally, the data in this study are based on a single-level structure, capturing only the individual perspective in perceiving the workplace climate. Future research would benefit from adopting a multilevel approach to capture the significance of shared experiences within teams or organizations concerning communality and agency. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how these climates impact group dynamics and organizational outcomes.

Another limitation lies in the absence of individual-level variables, such as social relationship needs. Incorporating these variables as potential moderators in future studies could shed light on the nuanced ways in which communal and agentic workplace climates influence individual well-being and engagement.

Furthermore, future research endeavors should explore additional attitudes and behaviors of employees within organizations as potential consequences of communal and agentic workplace climates. Examining a broader spectrum of outcomes will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of these workplace climates on various facets of organizational life.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting the findings of this article are available in the OSF repository, accessible via an anonymized link: https://osf.io/4vwz6/?view_only=1a481c457049444da8a7c91b4053a8cb