BACKGROUND

WORK ENGAGEMENT AND EMOTIONAL ATTITUDE TO WORK

Work engagement is a construct raising multiple interpretation doubts. Some (cf. Maslach, 2011) identify it with professional burnout, positioning both constructs on a single continuum. Initial studies on engagement put it at the opposite extreme of professional burnout, as a status opposite to emotional exhaustion or lack of accomplishments or cynicism (Maslach et al., 2001). By juxtaposing work engagement and professional burnout, its three components were indicated, i.e. the level of energy (opposite of exhaustion), devotion to work (as an antagonism of cynicism) and feeling of efficiency (opposition of reduced self-esteem). In turn, other researchers (cf. Bakker & Demerouti, 2008) note that the lack of engagement does not have to lead to professional burnout, as it may be a type of a strategy used for saving personal emotional or cognitive resources. Work engagement is seen as a sphere of personality conditioning work efficiency (Otrębski, 2023; Ronginska & Gaida, 2003). It comprises five dimensions: subjective significance of work in personal life, striving for professional promotion, readiness to make energy expenses for the sake of the performed work, striving for perfection and reliability during performance of obligations and ability to distance oneself and to take mental rest from work. Their intensification and constellation reflect the employee’s attitude to the fulfilment of professional obligations (Basińska & Andruszkiewicz, 2010). They result from expectations with respect to the work environment, as well as earlier experiences of the individual as far as coping with stress and determinants of successes and failures are concerned. Work engagement understood as a personal resource makes the individual accept an active role in the formation of conditions thanks to the access to the recognition of possible threats and preventing them (Schaarschmidt, 2006). The emotional attitude to work may, in turn, be understood as a subjective experience of professional success, satisfaction with life and sensation of social support (Rogińska & Gaida, 2003). The intensity of these variables is significantly conditioned by effective struggles with professional problems and the individual mode of coping with work requirements by creating a specific defence factor in critical and difficult situations.

Four models of behaviour with respect to the requirements at work may be differentiated. The healthiest model of behaviour indicating a healthy attitude to work (type G) assumes that the level of engagement is clear, yet not exaggerated, with a simultaneously moderate level of subjective significance of work (Schaarschmidt, 2006). Ambition is perceived most strongly, while the subjective significance of work, a tendency for energy expenses and striving for perfection have average or slightly higher values. However, the ability to keep distance with respect to work is important. The unambitious type (S) has the lowest results in the area of work engagement characterised by a very low level of work significance, professional ambitions, the desire to expend energy and striving for perfection. In turn, it has the clearest capacity for distancing, as compared to any other models. The risk type (A) is characterised by excessive engagement – it is manifested most strongly in the context of subjective significance of work, the desire to expend energy and striving for perfection. Meanwhile, the ability to distance oneself from work and tasks has the lowest values. This model of behaviour is related to health problems and occurrence of negative emotions. In turn, the exhausted type (B) is distinguished by a very low level of engagement and reduced capacity to distance oneself, and a low level of subjective significance of professional work and ambitions.

There is no doubt that work engagement, as well as the emotional attitude to work, creates a positive frame of mind related to work (Schaufeli et al., 2002; Walczak & Vallejo-Martín, 2021). They are accompanied by enthusiasm and energy. Additionally, they are related to such personal resources as optimism, self-efficiency, self-assessment, resistance and use of active coping strategies with difficulties (Luthans et al., 2008). An engaged employee is characterised by vigour, devotion and engagement (Schaufeli et al., 2002). The level of work engagement may affect the self-esteem of individuals by providing the employee’s life with purpose and sense (Peplińska et al., 2017). An individual is successful because he/she efficiently influences the environment by adjusting it to the requirements (Luthans et al., 2008). The studies show that a dependency exists between engagement and emotional attitude to work and the employee’s efficiency (Demerouti & Cropanzano, 2010). This is related to positive emotions (cf. Bakker & Demerouti, 2008), health (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) and the ability to mobilise resources (Fredrickson, 2001). Hence, engagement and satisfaction, next to mental immunity, are the external resources of an individual, warding off the risk of occurrence of professional burnout (Rongińska & Doliński, 2019). Apart from the indisputable impact of engagement on the results of an individual, it is possible to see a transfer of engagement to others (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008).

WORK-FAMILY RELATION

Work and personal life are the most important areas of man’s activity where significant needs are satisfied, affecting the overall level of satisfaction with life (Barnett, 2008; Oskarsson et al., 2021). However, they are also related to special tasks and duties, which often determine strong flows between them. Edwards and Rothbard (2000) describe six mechanisms that are quoted in the reference books with respect to the work-family relation. These are: spillover, compensation, segmentation, resource drain, congruence and work-family conflict. These mechanisms clarify the relationship between family and professional life, while the resource drain and the work-family conflict encompass the effects of such a relationship. An exchange or interaction assumes that experiences derived from one area affect other areas (Rothbard & Dumas, 2006). It may happen on account of similarities between the performed roles or on account of transfer of experiences from one area to another (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000). Congruence is related to a positive relationship between professional and non-professional experiences, yet it is caused by a third factor (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000). Compensation in the work-family area consists in the fact that a person compensates for the lack of satisfaction in one field with greater engagement in the other role (Oyewobi et al., 2022). The studies of Rothbard (2001, according to: Rothbard & Dumas, 2006) show that women who experience a negative relationship in the non-professional area become more engaged in work. Segmentation refers to a situation when work and family life do not have any impact on each other – the individual establishes a clear border between the performed roles (Rothbard & Dumas, 2006).

Simultaneous performance of two roles, in the family and the professional one, may exert a negative or positive impact (in both directions). It may lead to a conflict caused by stress and tensions resulting from the necessity of sharing and proper organisation of work (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). In turn, so-called facilitation means positive effects of performing these roles, e.g. development or better functioning. The work-family conflict touches on three different aspects of life and demands with respect to the roles performed by the individual (O’Driscoll et al., 2006). They are related to the time that has to be distributed among activities, tension and stress transferred from one area to the other and behaviour required during the performance of the individual roles. The conflict may be a result of internal (resulting from psychological work engagement or family) or external interference (resulting from behavioural work engagement or family) (Carlson & Frone, 2003, according to: O’Driscoll et al., 2006). The work-home facilitation may result from specific personality traits, e.g. conscientiousness, agreeableness and openness (Wayne et al., 2004, according to: O’Driscoll et al., 2006). Facilitation is also conditioned by the selective boundary permeability, which means use of certain skills and knowledge from one area in another area (Grzywacz, 2002, according to: O’Driscoll et al., 2006). In turn, facilitation results in better functioning in two areas, increases engagement, satisfaction and quality of interpersonal interactions, and has a positive impact on efficiency (O’Driscoll et al., 2006).

DUAL CAREER COUPLES

Cultural, social and economic transformations also affect the marriages that are solemnised and the families that are set up (Rostowski, 2009). With respect to the observed models of relations/marriages, three are nowadays dominant: traditional, egalitarian/partner and dual career (Dakowicz, 2014). It is necessary to make a distinction between the classic two-salary marriages (egalitarian/partner) and dual career marriages (Janicka, 2014, 2017). It is not easy given the growing requirements and labour market competition. In both types of marriages, a growing level of engagement in the performance of professional obligations is observed, with simultaneous reduction or abandonment of family obligations. However, the differentiating factor is the individual’s level of engagement in the process of adjusting personal professional competence and aiming for a better professional position, e.g. via promotion. In other words, it is the professional position of the partners that determines such differences. Work engagement is related to such variables as responsibility, liability, loyalty, devotion and investment of time and energy (Janicka, 2014; Schoebi et al., 2012). Reference books also indicate the quantity and quality dimension of a career (Crossfoeld et al., 2005), as well as the vertical and horizontal dimension (Paszkowska-Rogacz & Dudek, 2012). The quantity dimension takes into account the number of hours spent at work and working, the position in the organisation’s hierarchy and the number of performed tasks and positions held (Janicka, 2014). The quality dimension of the career most often refers to the degree of work engagement and satisfaction with work. The horizontal dimension of a career is understood as a competence extension process, development or building the career capital (Bańka, 2006), while the vertical one is understood as movement within the structure of the organisation to the top, i.e. vertical promotion (Janicka, 2014; Paszkowska-Rogacz & Dudek, 2012).

According to Markman et al. (2006; Janicka, 2014), dual career couples can be divided according to the stage of the professional career at the moment of marriage solemnisation. Here, early and late career relations are distinguished. The first category includes marriages where both partners at the moment of marriage solemnisation manifested high engagement in their careers. A similar level of aspiration, ambition or professional goal characterised both partners. Markman et al. (2006) call these persons ‘wed to work’ on account of marrying a partner with his/her work. The second group comprises partners in egalitarian/partner relations (two salary), in whom the high level of work engagement emerged after the solemnisation of marriage.

As compared to the traditional and egalitarian/partner (two salary) model of marriage, the relationship of two careers entails more sacrifices and threats, but may also be related to diverse benefits (Abele & Volmer, 2011). These primarily include higher family income, formation of a pro-active stance in children by showing them positive models, greater opportunities for success, increase of social and professional competence, a broader range of sources of support, the possibility of transferring positive experiences or change of style of spending leisure time, entertainment or recreation (Anderson & Spruill, 1993). Mutual positive flows may occur between the areas of professional and personal life, determining the mutual level of experienced satisfaction (Compos et al., 2013). These dependencies may be circular in character, i.e. the satisfaction experienced in one area, e.g. professional, positively affects the increase of satisfaction in another one, e.g. family, manifested via close relations and causing, indirectly, an even greater increase of satisfaction with personal professional activity. However, it is noticeable in the reference books that the multitude of benefits resulting from the multiple roles, in particular reconciliation of family and professional roles, is not unconditional. The quality of relations between partners affecting the level of support, love, understanding and the quality of communication between partners are reported as the most significant determinants in this area (Skowroński et al., 2014). Additionally, the determining variables for these relations include, among others, the fact of having children and the number of children, personal resources of partners, socio-economic status of the couple, as well as external factors, for example the system of family support offered by the state.

Many studies draw attention to the negative consequences resulting from the specific nature of dual career relationships, i.e. physical and emotional burdens, pressure of time, high number of tasks resulting from the diversity of roles, lack of free time or the necessity of continuous negotiation and renegotiation of obligations in a family (Abele & Volmer, 2011; Mäkälä et al., 2011; Rostowski, 2009). Additionally, negative nutrition changes are listed, as well as discontinuation of entertainment and recreation by the partners, insufficient amount of sleep, neglect of important development tasks, lowering of the subjective quality of life, and – to a greater degree – growth of stress, occurrence of health problems, and problems related to depression (Janicka, 2008). The partners in dual career relationships manifest the highest stress sensation indicators, along with tiredness and tension. They experience conflicts of roles much more often, along with the lowest indicators of affirmation of life and satisfaction with the forms of leisure time as compared to the other models of relationships (i.e. traditional and egalitarian/partner) (Peplińska et al., 2014). Simultaneously, the aforementioned partners show the highest indicators of satisfaction with personal accomplishments and satisfaction with the economic situation of the family, which may reduce the negative impact of the experienced stress and conflicts.

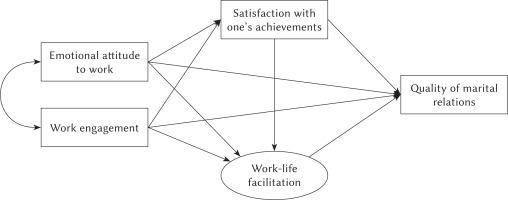

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the dependencies between the level of professional and emotional work engagement and the quality of the marital relationships of partners in a dual career relationship and search for additional mediating factors in this relationship – mediators, i.e. satisfaction with one’s accomplishments and facilitation of roles and moderators of the observed dependencies – type of relationship.

Bearing in mind the studies previously carried out in this area (Carlson & Frone, 2003; Janicka, 2017; Peplińska et al., 2014), an assumption was made that the level of work engagement and emotional attitude to work would be negatively related to the quality of marital relationship. A high level of engagement in professional roles and emotional attachment to work may lead to a conflict of roles experienced significantly more frequently and unfortunately to neglect in the area of relations between partners (Chen & Ellis, 2021; O’Driscoll et al., 2006; Yoo, 2022). Nevertheless, it should be remembered that a high level of engagement in and attachment to work may also be a source of positive experiences and satisfaction with one’s achievements, which may positively affect the other areas of the individual’s functioning (Gahlawat et al., 2019; O’Driscoll et al., 2006; Peplińska et al., 2018). Hence, it was additionally assumed that satisfaction with one’s achievements and work-family facilitation would be a significant mediating factor in the aforementioned relationship, moderating the association outlined above. It was also assumed that the relationship of two careers (early career vs. late career) would be a significant moderator of the analysed dependencies (Janicka, 2014; Markman et al., 2006). Bearing in mind the specifics of both groups, it was assumed that the positive flows which may moderate the negative consequences of work burdens and excessive work engagement would be characteristic for the early career relationships. An outline of the theoretical model subjected to verification is presented in Figure 1.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study included 184 dual career couples (368 persons), among which over 63% were formalised relationships – marriages. The age of the respondents ranged from 28 to 43 years of age. A definite majority of the respondents (89.7%) had higher education. All the couples had at least one child. With respect to the type of relationship, 69 pairs were so-called ‘early career’ relationships and 115 pairs were so-called ‘late career’ relationships. The majority of the respondents (over 74%) worked in the private sector, in corporations and organisations of various industries. The remaining part of the respondents worked in the public sector.

MEASURES

The following research methods were applied:

The AVEM (Arbeitsbesorgenes Verhaltens- und Erlebenmuster) test created by Schaarschmidt and Fischer (Schaarschmidt, 2006) in the Polish adaptation of Rongińska and Gaida (2003), comprising 66 statements assessed by the respondents on a 5-point scale with respect to accuracy in relation to their own feelings and experiences. The purpose of the test is to define individual resources of respondents in the context of coping with the demands of a professional situation. The structure of the test accounts for the measurement of three basic spheres of personality: work engagement (perceived significance of work, career ambitions, readiness to expend energy, striving for perfection, emotional distancing); resistance to stress; and emotional or subjective well-being (work satisfaction, life satisfaction, perceived social support). The evaluation of reliability of scales for the Polish version showed satisfactory results (Cronbach’s α between .71 and .84) and thus the possibility of applying the test in the studies of the Polish population. The described study also accounted for the scale of work engagement and emotional well-being. Sample items of the questionnaire: “The basic content of my life is work”; “When I’m working, I don’t spare myself”; “My professional successes are evident”.

The Work-Family Fit Questionnaire prepared for a research project carried out in the USA (Grzywacz & Bass, 2003) and adapted for the Polish conditions by Lachowska (2008). It comprises 16 questions evaluating the degree of experiencing a conflict of roles (negative impact of work on the family or the family on work) and facilitation of roles (positive impact of work on the family and the family on work). The Cronbach’s α coefficient values for individual scales range from .72 to .81. Sample items of the questionnaire: “Stress at work makes you nervous at home”; “A successful day at work makes you more social when you get home”; “Talking to someone at home helps you deal with problems at work”.

The Well-Matched Marriage Questionnaire (KDM-2) of Rostowski and Plopa (2005) for describing the quality of a marital relationship in the perception of each of the partners. As part of the tool, a general measurement of the level of quality of a marital relationship can be made, along with the level of detailed factors, such as intimacy, self-fulfilment, similarity and disappointment. The reliability coefficient values for individual scales range from .82 to .90. Sample items of the questionnaire: “In our free time we try to stay together”; “We agree with each other when it comes to how we spend our free time”; “I feel more comfortable in the workplace than at home”.

Feeling of Happiness Questionnaire based on Czapiński’s (1994) concept of happiness examining the level of satisfaction of the respondents in various areas of their life (such as relations with the family, financial situation of the family, situation in the country, health condition, but also life/professional accomplishments). Furthermore, it allows one to assess the level of satisfaction with life so far and the desire to live (Peplińska, 2011). Its structure resembles a questionnaire. For the purpose of this study, the measure of satisfaction with one’s accomplishments was used. The reliability level of the dimension measured with Cronbach’s α in the present study was .76. Sample items of the questionnaire: “How satisfied are you with your achievements in life?”; “How satisfied are you with your family’s financial situation?”; “How satisfied are you with your future prospects?”.

PROCEDURE

The study was carried out between 2013 and 2018 by contacting the respondents directly. The sampling was purposive. The qualification criterion for the dual career relationship category was the model of professional functioning of both partners based on the following parameters: high level of qualifications held – higher, specialist education, high specialist professional qualifications, work at a managerial/decision-making position; specific character of work requiring flexibility and high involvement in work (over 40 hours per week, work for more than 5 days a week, bringing some of the work home – reports, etc.); specific character of work related to significant liability, over-burdening with the role, pressure of time and stress. All of these parameters were included in the survey that respondents received with questionnaires. The qualifications for both groups were made by examiners on the basis of the described criteria. The partners were contacted directly using the ‘snowball’ method and via social networking media. Some studies were performed by the students from the Institute of Psychology of the University of Gdansk as part of a course and a master’s degree seminar. Each of the partners in the relationship received a set of questionnaires in a paper form. They were returned, on average, within 3-7 days in sealed envelopes. The respondents were informed about the purpose of the performed study, as well as about the possibility of receiving individual feedback after the end of the study.

RESULTS

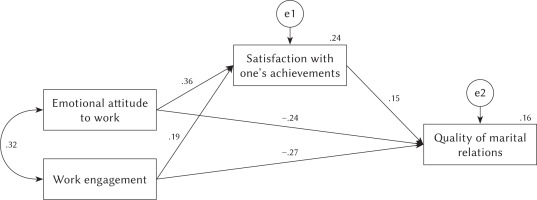

To verify the assumptions about a significant relation of emotional attitude to the performed work, the level of work engagement, the satisfaction of one’s achievements and experienced facilitation and the quality of relationship in marriages of the employees covered by the study, modelling of structural equations using Amos24 was applied. The analyses indicated that the facilitation of roles does not form a significant intervening variable of the observed dependencies. Furthermore, it transpired as part of the analysed moderations that the presented model of dependencies fulfilled the requirements of adjustment to the data exclusively for the group of ‘late career’ couples (Tables 1-2).

Table 1

Model fit parameters for the ‘late career’ couples (N = 230)

| χ2(3) = 8.52, | RMSEA = .071 | GFI = .992 | CFI = .985 |

|---|---|---|---|

| p= .036 |

Table 2

Model fit parameters for the ‘early career’ couples (N = 138)

| χ2 (3) = 14.23, | RMSEA = .011 | GFI = .892 | CFI = .884 |

|---|---|---|---|

| p= .002 |

The parameters obtained for the model (Table 1) as a result of the performed analyses show that the model is interpretable and acceptable. They indicate (Figure 2) that there is a statistically significant, negative (β = –.24, p = .013) relationship between the emotional attitude to work and work engagement (β = –.27, p = .011) and the assessment of quality of marital relations. Furthermore, significant, positive relations of these variables with satisfaction with one’s achievements were also found (respectively: β = .36 and β = .19; p = .014), as well as between these accomplishments (β = .15, p < .05) and the quality of the marital relationship.

The analysis of direct and indirect effects in the model showed the mediating role of emotional attitude to work and the level of work engagement performance and the quality of marital relationship on the side of satisfaction with one’s achievements (Table 3). It was found that in both cases, they are a total mediator, moderating the significant relationship of the above variables and working as a buffer for this negative relationship.

Table 3

Mediating parameters on the side of professional achievements for ‘late career’ couples

DISCUSSION

The study showed that work engagement, which is accompanied by a strong positive emotional attitude to work, is negatively related to the quality of partner relations. The high level of engagement in the professional role and devotion to work may be a conflict-generating factor with respect to engagement in intimate roles. The authors of reference books (Frone et al., 1997; Janicka, 2008) indicate several basic dimensions of negative consequences of excessively high engagement in the professional roles and thus failure to keep a healthy balance between the professional life and personal life, i.e. the behavioural dimension (difficulties with time management, pressure); psychological (mental health, well-being, experienced stress), health (physical health, exhaustion) and social (engagement in social roles). In this area, the risk of non-fulfilment of non-professional tasks in the area of personal life, i.e. not solemnising a marriage and establishing a family (Duxbury & Higgins, 2001), but also consequences within the scope of the subjective quality of life, satisfaction and relationship with close persons are indicated. The experienced costs resulting from excessive engagement in professional work may thus reflect on the quality of a marital relationship and affect conflicts between the partners, weaken emotional ties and lead to the disappearance of intimacy and passion in a relationship (Frone et al., 1997; Rostowska, 2009). The category of relationships especially exposed to the threats above is the dual career marriage, where the level of engagement in professional roles of both partners is very high, while the potential risk of work-family conflicts is considerable. As already mentioned in the introduction to this paper, with respect to the scope of negative consequences resulting from the specific functioning of dual career partners, physical and emotional burdens, pressure of time, overburdening with tasks, obligations – including at home (Abele & Volmer, 2011), high level of experienced stress, tiredness or tension (Peplińska et al., 2014) are listed, which are in a negative relationship with the experienced sense of life. The studies quoted above form a basis for the formulated and confirmed hypothesis about the negative relationship between work engagement, emotional attitude to work and the quality of partner relations in dual career relationships. On the other hand, one should not forget about the positive aspects related to the high level of engagement in professional roles – not only in the aspect of the material status, but also benefits related to the possibility of self-fulfilment and satisfaction transferred to other areas of life, e.g. personal. Mutual positive flows may occur between the areas of professional and personal life, determining the mutual level of satisfaction experienced by the partners (Compos et al., 2013), including in the case of dual career marriages (Peplińska et al., 2018), especially due to the fact that work engagement, as well as the emotional attitude to work, makes up a positive frame of mind related to work (Schaufeli et al., 2002). However, it is important that it is not too high or too intense, so that we can speak about a pro-healthy attitude to work (Schaarschmidt, 2006). Nevertheless, it should be stressed that the dependencies noted in the present study refer exclusively to the so-called ‘late career’ relations. In the case of the ‘early career’ relations, no significant dependency between the analysed variables was observed. A probable factor influencing the dependencies noted in this way may be a form of a ‘contract’ between the partners, as opposed to the mere lasting of a relationship, which in the case of the ‘late career’ relationships is changed and may negatively affect the relations. This may also be related to the feeling of disappointment with the solemnised marriage (Godlewska-Werner, 2011). Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that in the case of an ‘early career’ relationship, the high level of personal work engagement characterised the partners already at the stage of entering into an intimate relationship. Thus maybe the passion for work and devotion to it were the factors uniting the partners and tightening their emotional bond. In the case of the ‘late career’ relations, the high level of emotional engagement in the professional role may have been an effect of the passion of self-fulfilment discovered later, but it also could have stemmed from dissatisfaction in other areas of personal life and constituted certain compensation with respect to it.

In line with the hypotheses made, satisfaction with one’s achievements was an important mediating factor in the analysed dependency. The performed statistical analysis showed that the satisfaction with one’s achievements moderates the relation between the emotional attitude to work and the level of engagement in its performance and the quality of marital relations. This means that a strong subjective significance of work related to readiness to expend energy lowers the quality of relationship in a marriage, yet the feeling of satisfaction with one’s achievements diminishes this relation. This is consistent with the observations indicating that the higher the satisfaction with work is, the greater is the satisfaction with personal life (cf. Sinacore & Özge Akçali, 2000). It may thus be concluded that if a high level of engagement and devotion to work is accompanied by a high level of satisfaction with one’s achievements, the negative flows in the area of partner relations are not so intense and significant. As observed in previous studies (Peplińska et al., 2014) satisfaction with the accomplishments of partners in dual career marriages was also an important moderating factor in the relation between the experienced professional stress and conflicts of roles and the quality of partner relations. Thus, one may venture to say that in the case of the examined group of partners in ‘late career’ marriages, the high level of emotional work engagement is not related to strongly experienced tensions and stress, which negatively affect the relations between the partners, but are levelled by the benefits resulting from such engagement, namely personal accomplishments.

CONCLUSIONS

Permanent mutual flows exist among individual areas of man’s functioning, which may significantly affect the quality of a person’s functioning in individual roles in life. These flows may both be positive (determining the level of experienced satisfaction and competence acquired), but also negative (transition of tensions, frustrations, overburdening with roles and tasks). Especially the negative aspects of these relations have long been a concern for the psychologists addressing the issues of work and family psychology. They are related to diverse high costs for the individual, but also costs for his/her environment, friends and family. As shown in the results of the studies above, a high level of engagement in the professional role may negatively affect the quality of partners’ emotional ties. However, the present study additionally shows that other variables are also involved in the mutual relations between professional work and personal life, which may significantly change this relationship. Hence, a conclusion is made pertaining, on the one hand, to the complexity of the analysed dependencies but also the necessity of continuing studies in this respect. The sole type of a relationship may be a significant moderating factor in the analysed relations. The present study indicates significant potential differences between the types of the so-called ‘early’ and ‘late’ career. In future studies, it is also necessary to take into account demographic variables, e.g. sex, as prior findings highlighted the differences between women and men within the scope of the work-home relations and variables related to this construct (e.g. Godlewska-Werner, 2011; Rothbard & Dumas, 2006).

LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

The present study allows for a broader look at the specifics of dual career relationships and the impact of work on the quality of relations. In spite of publications indicating that dual career relations are not homogeneous, there are relatively few studies presenting the differences between the ‘early’ and ‘late’ career relationships, in particular in the area of Polish studies. Unfortunately, the present study also has some limitations. One of the basic problems is the classification of couples in the category of dual career marriages. In spite of the adopted premises and criteria for this classification, there is always a risk of a certain lack of precision, as well as reliance on the subjective data received from the respondents. Additional limitations include the number of respondents – it would be advisable to increase the studied sample size, which would not only offer a basis for more justified generalisation of results, but also give greater possibilities of introducing additional intervening variables within the scope of the analysed dependencies. Based on the obtained results it was noted that there may be significantly more variables that may constitute an important intervening factor between the level of work engagement and the quality of partner relations, apart from sole satisfaction with accomplishments. Also of value would be comparative analyses taking into account additional moderating variables, such as the partners’ sex or the number of children. Finally, in-depth interviews (in the form of an extensive survey) with the possibility of individual statements (while maintaining anonymity) could be very valuable.