BACKGROUND

The feeling of interpersonal hurt and harm is a common phenomenon and often occurs after the experience of conflict, rejection, social pressure, and so on (Krug et al., 2002). These feelings can develop into chronic emotions (e.g., anger and hostility), which in turn can result in deterioration of psychophysiological health and the onset of distress (Akhtar et al., 2017; Goldman & Wade, 2012; Skalski-Bednarz & Toussaint, 2024). One method of dealing with the consequences of being wronged is forgiveness, which leads to a reduction in negative affect, thoughts, and behaviours toward the offender (Davis et al., 2015; Skalski-Bednarz, 2024), and the positive impact of such a practice on well-being has been confirmed by numerous meta-analyses (Akhtar & Barlow, 2018; Baskin & Enright, 2004; Fehr et al., 2010).

Most often, forgiveness is described as a process that one must go through to obtain a pardon so that the feeling of resentment toward the offender can end (Worthington et al., 2007). This stream points to intellectual forgiveness, which results in a decision to forgive (Davis et al., 2015), and the next step is followed by an emotional feeling that an act of forgiveness has taken place (Hook et al., 2012). Subkoviak et al. (1995) noted that in the process of forgiveness, the individual overcomes resentment toward the offender and seeks to adopt a new attitude of benevolent compassion or love toward them, “even though the latter has no moral right to such a merciful response” (p. 642). These words prompted Rye et al. (2001) to formulate the hypothesis that the forgiveness process consists of two types of independent responses by the victim toward the perpetrator; that is, it can involve both the absence of negative responses and the presence of positive responses toward the perpetrator. According to Rye et al. (2001), there are dispositional factors that predispose someone to forgiveness, such as an inclination to forgive (Brown, 2016) or a lack of vindictiveness (Stuckless & Goranson, 1992).

Forgiveness is widely regarded as a form of emotion-focused coping in response to stress. The construct is sometimes cast in the context of the transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and the stress-and-coping theory of forgiveness of others (Strelan, 2020; Worthington, 2006). Unique to this approach is the emphasis on transgressions (i.e., experienced hurt and harm) as life stressors and the role of forgiveness in coping with the resulting threats, judgements of injustice, and stress reactions (Worthington et al., 2019). For example, Toussaint et al. (2016a) noted that experiencing life events (often associated with a lack of forgiveness) is stressful and that forgiveness can initiate an adaptive coping response. At the same time, it should be noted that, in light of most available stress theories, active and adaptive coping reduces the impact of the aggravating stimulus and leads to a reduction in distress (e.g., according to Lazarus and Folkman [1984] under the so-called “reappraisal” of the situation). The existence of a negative association between forgiveness and stress is also consistently reported in scientific studies (Harris et al., 2006; Oman et al., 2010; Toussaint et al., 2016b).

In view of the promising literature, clinicians and policymakers interested in promoting well-being are increasingly interested in the health benefits of forgiveness (Akhtar & Barlow, 2018; Macaskill, 2005). On the other hand, researchers have pointed to the complex nature of forgiveness in terms of its impact on distress reduction and the existence of various mechanisms that underlie this relationship. For example, research has shown that forgiveness can have a direct impact on mental health but can also involve indirect pathways through such mechanisms as hopelessness and rumination (Cheng et al., 2021; Toussaint et al., 2008, 2023). Toussaint et al. (2008) also noted that both forgiveness and hope involve deciding that one wants to achieve a goal (e.g., resolve a conflict) and then working together with the offender to identify pathways to that commitment, despite the existence of potential obstacles. Seybold et al. (2001), on the basis of the premise that forgiveness reduces hostility (which is considered alongside anger as a dimension of aggression and is one of the main correlates of type A behaviour; Billing & Steverson, 2013), proposed various pathways linking forgiveness to health, including healthier behaviour and transcendent or religious factors. The latter include a range of cognitive and behavioural techniques that help individuals cope with or adapt to difficult life situations (Denney & Aten, 2020). Ysseldyk et al. (2009) noted that the link between forgiveness and less suffering is the reduction of cognitive processes that could result in the escalation of negative emotional aspects of the situation. Some theorists and researchers believe that forgiving individuals are more likely to perceive and receive social support effectively, whereby they experience higher levels of well-being (Worthington & Scherer, 2007; Ye et al., 2022). These assumptions were also confirmed by Zhu (2015), who demonstrated the mediating role of social support in the relationship between forgiveness and life satisfaction. Finally, the set of potential mediators in the relationship between forgiveness and distress should include perceptions of health itself because, according to Skalski (2018), a feature in the cognitive assessment of health complaints is the impact of distress on functioning in many areas of life, including determining emotional responses. On the other hand, according to Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) theory, forgiveness can be an effective technique for dealing with the negative evaluation of health in terms of obstacles/loss, which consequently reduces distress.

The existence of a multidimensional relationship between forgiveness and distress can also be described on the basis of the biopsychosocial-spiritual model (Hatala, 2013; Sulmasy, 2002), which assumes that feeling burdened is determined by a number of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual factors, whereas the level of health is determined by generalised immune resources. Significant stressors in the context of this model include struggling with a difficult situation, vulnerability to depression, feelings of hopelessness, social isolation, or a lack of adequate support in coping with stress. According to Saad et al. (2017), biopsychosocial theories have particular practical implications in health care systems, where the importance of the complexity of health problems is increasingly recognised.

Because previous reports have identified many factors that influence perceptions of trauma and distress (e.g., Henselmans et al., 2010; Kagee et al., 2018), and at the same time many studies have identified forgiveness as a critical resilience resource (e.g., Akhtar & Barlow, 2018; Lee & Enright, 2019), in this study we set out to assess the association of forgiveness and distress through five different pathways. On the basis of the previous literature review, we formulated a working hypothesis according to which the negative relationship between forgiveness and distress is multidimensionally mediated by five pathways: (a) health (involving vitality and symptoms of illness), (b) negative outlook on the situation (pessimism and hopelessness), (c) religious-spiritual resources, (d) aggressiveness (anger and type A personality traits), and (e) social support (from friends, family, and significant others). Given that, according to Toussaint et al. (2001), forgiveness may have a greater impact on the health of older adults, in this study we attempted to examine the relationship between this forgiveness and distress among young adults. Our aims were to determine whether forgiveness of others was associated with distress in adolescents and young adults and to identify sociopsychological factors that may enhance the benefits of forgiveness for mental well-being in this age group.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

The study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of Economics and Human Sciences in Warsaw (#04/06/2022). Before taking part, each participant gave informed consent. Data from anonymous online surveys were collected. Apart from the age criterion (18-29 years), no additional recruitment conditions were required. Incomplete data were excluded from the analyses (i.e., eight surveys).

PARTICIPANTS

The final sample consisted of 436 participants (Mage = 25.39 ± 6.10), 62% of whom were women. The study procedure consisted of completing questionnaires assessing forgiveness, distress, health, negative perceptions of the situation, religious-spiritual resources, aggressiveness, and social support. The average time to participate in the survey was 20 min.

MEASURES

The Rye Forgiveness Scale. To measure episodic forgiveness, alternatively referred to as state forgiveness, we used the Rye Forgiveness Scale (RFS; Rye et al., 2001). The RFS consists of 15 statements assessing affective, cognitive, and behavioural forgiveness toward a particular perpetrator. The respondent expresses their attitude toward each statement on a scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Although the RFS measures both absence of negative and presence of positive forgiving responses to wrongdoing, in this study we reported only the total forgiveness score (α = .87). In the validation study, the RFS score was significantly positively correlated with other measures of forgiveness, religiosity, hope, religious and existential well-being, and social desirability, and negatively correlated with anger. Sample items are “I can’t stop thinking about how I was wronged by this person” and “I have compassion for the person who wronged me”.

The Vitality Plus Scale. We used the Vitality Plus Scale (VPS; Myers et al., 1999) to measure health through potential physical health benefits. The VPS consists of 10 items that load onto a single factor (α = .83) that describes various elements of physical health (including pep and energy, ability to fall asleep quickly, aches and pains, feeling rested, and appetite). The respondent expresses their attitude toward each statement on a scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items are “I sleep well” and “I am full of pep and energy”.

The Physical Health Questionnaire. In contrast, we used the Physical Health Questionnaire (PHQ; Schat et al., 2005) to measure health through symptoms of illness. The PHQ consists of 14 statements covering four dimensions of somatic symptoms: (a) gastrointestinal problems, (b) headaches, (c) sleep disturbances, and (d) respiratory illnesses. The respondent expresses their attitude toward each statement on a scale that ranges from 1 (not at all) to 7 (all of the time). In the validation study, the PHQ score was related to measures of negative affect and mental health. For the purposes of our project, we used the total scale score (α = .84). Sample items are “How often did you feel nauseated (‘sick to your stomach’)?” and “How often have you had difficulty getting to sleep at night?”

The Life Orientation Test. To measure negative outlook through pessimism, we used the pessimism subscale of the Life Orientation Test (LOT; Scheier et al., 1994). The pessimism scale consists of three items assessing generalised expectations of negative outcomes. The respondent expresses their attitude toward each statement on a scale that ranges from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). A sample item is “I hardly ever expect things to go my way”. We also used a two-item hopelessness scale developed to measure negative views of oneself and the future (Everson et al., 1996; Fraser et al., 2014). This two-item scale is internally reliable and stable over time and has excellent concurrent validity with the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Beck et al., 1974) and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale. Items are responded to on a five-point 0 (disagree) to 4 (agree) scale where higher scores indicate greater hopelessness. The two items are: “I feel that it is impossible to reach the goals I would like to strive for”, and “The future seems to me to be hopeless, and I can’t believe that things are changing for the better”.

The Duke Religion Index (DRI; Storch et al., 2004) was used to measure religiosity. The DRI consists of five items that load onto a single factor (α = .91) that measures dimensions of religiosity through organisational (worship attendance), nonorganisational (prayer or religious instruction), and intrinsic (three items; e.g., experience of God’s presence) components. Responses to the organisational and nonorganisational subscale items are rated on a frequency scale that ranges from 1 (never) to 6 (several times a week). For the intrinsic subscale, the respondent expresses their attitude toward each statement on a scale that ranges from 1 (definitely not true) to 7 (definitely true). In our analyses, we used only data from the intrinsic religiosity subscale.

The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale. To measure spirituality, we used the brief version of the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES; Underwood & Teresi, 2002). This single-factor (α = .91) tool includes six statements that assess ordinary spiritual experiences, such as awe and joy, that lift us out of everyday life and impart a sense of deep inner peace. The respondent indicates the frequency of each experience on a scale that ranges from 1 (never or almost never) to 6 (many times a day). Sample items are “I feel God’s presence” and “I experience a connection to all life”.

The State-Trait Anger Inventory. To measure aggressiveness through the trait of anger, we used the State-Trait Anger Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1983), with 10 statements that load onto a single factor (α = .84). Participants are asked to rate how they generally feel when they are angry or upset on a scale that ranges from 0 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Sample items are “I get angry when I am slowed down by others’ mistakes” and “I feel annoyed when I am not given recognition for doing good work”. We used the Framingham Type A Behavior Pattern Scale (MacDougall et al., 1979) to measure aggressiveness through the severity of type A personality traits. The questionnaire consists of 10 self-report items that load onto a single factor (α = .81). For the first five statements, the respondent expresses their attitude on a scale that ranges from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very well). The next five items require a yes/no response (recoding: 1 for indicating a trait and 0 for no trait). Sample items are “Traits and qualities which describe you… ‘Being hard-driving and competitive’ and ‘Usually pressed for time”.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. To measure social support, we used the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., 2010). The scale includes 12 statements that address three different types of social support: (a) family (α = .91), (b) friends (α = .87), and (c) significant others (α = .85). In the validation study, high levels of perceived social support were associated with low levels of depression and anxiety symptomatology. During the survey, the respondents expressed their attitude toward each statement on a scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items are “There is a special person who is around when I am in need” and “There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows”.

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6; Kessler et al., 2002) was used to measure psychological distress. The scale consists of six statements that load onto a single factor (α = .89). In validation studies, the K6 showed high convergence with the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (First, 1997). This tool is widely used in health measurements in the United States and Canada, as well as in the World Health Organisation’s World Mental Health Surveys. During the survey, participants indicate how often they have had six different feelings or experiences – (a) nervous, (b) hopeless, (c) restless or fidgety, (d) so depressed that nothing could cheer you up, (e) that everything was an effort, and (f) worthless – in the past 30 days on a scale that ranges from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). Sample items are “There is a special person who is around when I am in need” and “There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows”. In addition, we used the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Lee, 2012) to measure stress. The tool consists of 10 statements that load onto a single factor (α = .78). In validation studies, the overall perceived stress factor was positively related to depression, anxiety, and anger scores. On the PSS, the respondent indicates the frequency of various behaviours or experiences during the past month on a scale that ranges from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Sample items include: “During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel... ‘nervous?’ and ‘so depressed that nothing could cheer you up?”.

STATISTICAL DATA ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis of the data was carried out using SPSS Statistics version 28 and Amos version 28. We verified the normality of the variable distributions using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and verified the homogeneity of the variance using Levene’s test (the results allowed the use of parametric tests). A Pearson correlation analysis and structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis using maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation were used to determine relationships between variables. The following indices were used to assess the fit of the model to the data in SEM: relative chi-square (χ2/df), comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardised root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Values of χ2/df < 2 suggest a good fit of the model to the data. Similarly, a CFI > .9 indicates a good and adequate fit of the model to the data. Finally, RMSEA and SRMR values < .08 should also be interpreted as an acceptable fit to the data (Kline, 2015).

RESULTS

A correlation analysis revealed statistically significant relationships: state forgiveness showed a large negative correlation with pessimism; a medium positive correlation with family and friend support; a medium negative correlation with illness symptoms, trait anger, perceived stress, and psychological distress; a small positive correlation with vitality, intrinsic religiosity, daily spirituality, and significant other support; and a small negative correlation with hopelessness and type A personality. Perceived stress and psychological distress were strongly positively intercorrelated; each showed a large positive correlation with illness symptoms and pessimism; a large negative correlation with vitality; a medium positive correlation with hopelessness, trait anger, and type A personality; a medium negative correlation with family support; and a small negative correlation with friend and significant other support. Other correlation effects (between variables that will be assumed as potential mediators in the next step), means, and standard deviations are shown in Table 1. Gender (0 – woman, 1 – man) was weakly positively associated with family, friend, and significant other support; perceived stress; and psychological distress. Age was not correlated at a statistically significant level with the results.

Table 1

Means and correlations

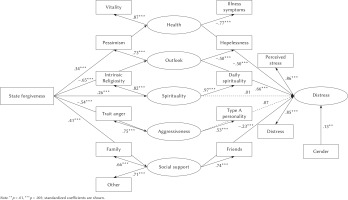

We then used SEM with latent mediators and a latent distress outcome variable to test the hypotheses. We examined the extent to which the association between state forgiveness and the latent distress variable (including perceived stress and psychological distress) was mediated by health (vitality and illness symptoms), outlook (pessimism and hopelessness), spirituality (intrinsic religiosity and daily spirituality), aggressiveness (trait anger and type A personality), and social support (family, friend, and significant other support). The model was found to be a reasonable fit to the data: χ2(71) = 133.75, p < .001, χ2/df = 1.88, CFI = .971, SRMR = .042, RMSEA = .055, 90% CI [.043; .067]. Figure 1 depicts the standardised path coefficients. The model allowed correlation of residual values between all latent mediators (see Table 2); however, for better clarity, we have not marked these covariance estimates in the figure. State forgiveness and the latent mediators explained 65% of the variance concerning distress.

Figure 1

Study model: Relationships between state forgiveness, health, spirituality, aggressiveness, social support, and distress (N = 436)

Table 2

Correlations of residual values between all latent mediators (N = 436)

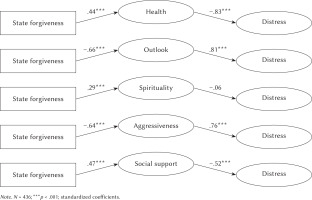

The hypothesised model showed a statistically significant total indirect effect (β = .48, p < .001) through the five latent mediators. Because no test of individual mediators currently exists for multiple-mediator SEMs (in Amos), we tested the individual latent mediators in separate models. Fit indices and indirect effects are given in Table 3. Models and path coefficients are presented in Figure 2. Moreover, the following total effect not included in the model was observed: state forgiveness (β = –.48) was a statistically significant predictor of the latent distress variable (p < .001).

Table 3

Structural equation model estimation and indirect effect in simple mediator models (N = 436)

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to assess the relationship between forgiveness status and distress by analysing the pathways of health, negative outlook, religious-spiritual resources, aggressiveness, and social support. The multiple-mediator model provided information on the mediating effects of sets of different variables and the relative size of each mediator, and further analysis allowed us to assess the mediating effect of each mediator compared to other proposed variables.

The significant relevant indirect effects in this study suggest that various sociopsychological variables may underlie the relationship between forgiveness and distress. The data obtained also suggest, to some extent, that the reduction of perceived stress occurs through complex coping mechanisms; that is, different attitudes, experiences, and behaviours may influence each other and jointly contribute to the reduction of distress in young adults. On the other hand, the results for specific indirect effects revealed that the high validity of variables such as health, negative outlook (the largest effect), aggressiveness, and social support play a special role in adaptation to stressful life events in forgiving individuals, which in turn indirectly corresponds to the existing literature on predictors of stress and health (Cheng et al., 2021; Seybold et al., 2001; Toussaint et al., 2008; Zhu, 2015). According to the hypothesis we formulated, these various sociopsychological variables appeared to explain the negative association between forgiveness of others and distress. Thus, our observations provide empirical support for the biopsychosocial model (Hatala, 2013; Sulmasy, 2002), according to which distress depends on the interaction of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual factors.

The results on the relationship between forgiveness and distress are consistent with the consensus in the literature that a lack of forgiveness is stressful and can initiate an adaptive coping response through forgiveness (Worthington et al., 2019). At the same time, our findings support the idea that forgiveness helps individuals reduce or manage their negative affect (Marks et al., 2013; Worthington & Scherer, 2007), thus helping them remain more directly involved in coping with intra- or interpersonal stress. Similarly, in a recent study, Gall and Bilodeau (2020) noted that engaging in forgiveness is associated with experiencing emotional and psychological well-being. In their study, rates of forgiveness were associated with better adjustment, higher self-esteem, and a greater sense of hope. The same authors also noted that forgiveness can enhance the effects of other coping techniques – for example, emotional and benevolent forms of forgiveness fully mediated the relationship between positive reframing and cooperative spiritual coping and the experience of positive affect (Gall & Bilodeau, 2020).

Despite expectations, we did not observe a mediating effect of religious-spiritual resources in the relationship between forgiveness of others and distress (there was a nonsignificant path in the multiple-mediator model and nonsignificant statistics for specific indirect effects). Although, according to several studies (Lampton et al., 2018; Stratton et al., 2008), religious-spiritual resources may provide motivation for forgiveness through devotion to faith or personal spirituality, according to Rye (2007), secular forgiveness techniques are as effective as their religious counterparts, which in turn may explain the nonsignificant effect in our study. Rye’s findings were supported by a later meta-analysis by Worthington et al. (2011), according to which religious-spiritual adaptations of accommodative interventions generally have no additional mental health benefits over traditional secular programmes (only that they may increase indicators of spiritual well-being). Regardless of the lack of mediating effect, in our study religious-spiritual resources did not correlate significantly with either forgiveness or health, which remains contrary to the consensus in the literature (Maier et al., 2022; Skalski-Bednarz et al., 2022; Skalski et al., 2024). An explanation for this situation may be the decline in religious identity in the under-30 population (Huskinson, 2020). Perhaps secularised young adults are using other techniques and value systems than religion to make meanings for coping with adversity. However, further research in different age groups is needed to verify this hypothesis.

Another interesting observation concerns aggressiveness (which includes measures of anger and type A personality traits). For this variable, on the one hand, we found a nonsignificant path in the multiple-mediator model and, at the same time, a significant statistic in the analysis of specific indirect effects. This may be due to the associations of aggressiveness with health and social support and negative perceptions of the situation. Together, these three covariables explain the same proportion of the variance in the endogenous variable as aggressiveness. At the theoretical level, this can be explained by the General Aggression Model (DeWall & Anderson, 2010), according to which the adoption of aggressive behaviour is influenced by situational variables, available affect, and cognitive content, which ultimately lead to thoughtful or impulsive behaviour – in this case, one should consider that positive evaluations in health, social support and outlook can reduce the severity of aggressiveness.

Finally, it is important to note the gender differences in distress, social support, and aggressiveness. Young men were more likely to report higher rates of distress than young women (because of this, we included gender as a covariate in the model). An explanation for this observation may be Möller-Leimkühler’s (2002) hypothesis related to help-seeking in stressful situations, according to which young men experiencing high levels of distress do not ask for help either on their social networks or from professionals, making it difficult to reduce perceived tension. In addition, men in our study reported higher rates of social support, which corresponds with some research (e.g., Kutner & Brogan, 1980; Xu & Burleson, 2001). These observations are often explained by gender differences in socialisation experiences and gender-related social roles (Matud et al., 2003). On the other hand, recent reports suggested that low perceived social support in women may also be associated with poor self-ratings in specific factors of health ([see Caetano et al., 2013; Pettus-Davis et al., 2018]; but in our study, we did not observe a gender effect on health).

LIMITATIONS

This study makes a significant contribution to the literature on the relationship between forgiveness and distress. Before generalising the findings more broadly, however, several limitations should be noted. First, the study was conducted among young adults. The severity of phenomena and effects in older populations may differ from those obtained in the study. For the same reason (the age homogeneity of the participants), it was not possible to include age as a moderator in the model. In our study, however, we wanted to look at the role of forgiveness in this narrow age group because previous studies have emphasised the benefits of forgiveness primarily in older adults (see Toussaint et al., 2001). Second, the study is correlational in nature. As such, it is impossible to make definite judgements about the causes and effects of the phenomena. Despite the grounding of our data in theories and empirical data, experimental techniques and longitudinal studies are necessary to unambiguously assess the impact. Finally, the stress data were collected in the general population. Thus, it should be assumed that the vast majority of participants were not exposed to chronic stress, and the data obtained should be viewed as an analysis of sociopsychological resources that may protect against distress. Because we examined only a general indicator of forgiveness of others, it would be interesting in future studies to include specific dimensions of forgiveness (e.g., forgiveness of self, forgiveness of others, forgiveness by God) to assess which specific aspects of the phenomenon are critical in coping with stress in young adults.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS: TOWARDS EDUCATION FOR FORGIVENESS

The subject of forgiveness specifically touches the sphere of feelings, attitudes, and values involved in and determining human development. Its positive effects on coping with stress highlight the need for stimulating, directing, and supporting forgiveness. Thus, in the teaching of the forgiveness process we should focus on educational action on those factors that have a direct impact on the process of forgiveness, that is, strengthening attitudes and beliefs that favour this process and, conversely, weakening those associated with a state of unforgiveness. Among the factors conducive to forgiveness are a proper understanding of forgiveness; the ability to see positive qualities in the offender; or, finally, the ability to communicate one’s own emotional states to others (Davis et al., 2015). In light of the data we obtained, one should assume that a developed attitude of forgiveness can be a key resource of resilience among people entering adulthood, which will translate not only into lower levels of perceived burden but also more frequent health-promoting behaviours, positive perceptions of the environment, lower aggressiveness and more use of social support. Among the methods for developing forgiveness, psychoeducation and therapy are most often indicated. For example, REACH Forgiveness training (see https://www.evworthington-forgiveness.com) provides an understanding of the phenomenon of forgiveness and identifies its benefits while promoting the decision to forgive and thus leading to emotional forgiveness. In contrast, numerous studies have indicated that immediate forgiveness training of even a few hours may be sufficient to develop a greater tendency to forgive in participants and experience some of the positive health effects of this technique (Akhtar & Barlow, 2018; Lin et al., 2014; Toussaint et al., 2020).

CONCLUSIONS

Our study strengthens the existing literature by providing a more detailed explanation of the links between forgiveness and distress. The relationships clarified illustrate how perceptions of burden are generated by the interaction of multiple factors. We have shown that the relationship between forgiveness and distress can be explained through complex sociopsychological mechanisms, including feelings of health, outlook, or social support, and attitudes, experiences, and behaviours related to these mechanisms can influence each other and collectively contribute to preventing or reducing perceived burden in young American adults. Thus, it is important to recognise that the relationship between forgiveness and distress is much more complex than the existing literature may suggest.