BACKGROUND

Trust is understood in a broad and multidimensional way, which is why it is difficult to define it in a way that could be accepted by all researchers. Positive expectations towards a person or group that the individual trusts and his or her vulnerability are the elements of many descriptions of trust (Simpson, 2007; Wade & Robinson, 2012). Trust – considering it in the context of organizations, social networks, groups, or nations – is a factor that strengthens their growth and established standards (Balliet & Van Lange, 2013).

Trust is important for interpersonal relationships. Simpson (2007) distinguished four basic principles of interpersonal trust. They state that: (1) observation of the partner’s behaviour in trust-diagnostic situations is used to assess the degree to which he/she can be trusted; (2) these diagnostic situations occur naturally, but can also be created by the person in order to evaluate the level of trust in the partner; (3) the increase or decrease of trust during the relationship may be influenced by differences in the partners’ attachment styles, their self-esteem or self-images; (4) without taking into account the dispositions and actions of both partners (especially in trust diagnosing situations), it is impossible to fully understand trust in a relationship.

In the context of close relationships, trust can be defined as a generalized positive expectation towards a partner (Rempel et al., 1985; Simpson, 2007; Wojciszke, 2006) and also as “confidence that [one] will find what is desired [from another] rather than what is feared” (Deutsch, 1973, p. 148, cited in: Simpson, 2007). Referring to Deutschen’s definition, Wojciszke (2006) suggests that for people in a relationship, the positive expectation of trust is related to the partner’s concern for the well-being of the trusting person and meeting their needs. The predictability of the partner’s behaviour is a prerequisite for trust, and its agreement is treated as the first stage of forming trust in a relationship.

Trust is one of the most desirable features of close interpersonal relationships (Simpson, 2007; Wojciszke, 2006). It increases the sense of security, reduces the inhibitions and defensiveness of partners, and allows them to share their feelings and dreams (after: Larzelere & Huston, 1980). It is a predictor of satisfaction with the relationship; what is more, it may be its most important element (after: Juarez & Pritchard, 2012). It is sometimes perceived as the foundation of commitment, satisfaction, cooperation, and the pace of initiating future relationships, and its loss may result in the termination of existing ones (Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Robinson, 1996, cited in: Balliet & Van Lange, 2013).

Considering the importance of trust in interpersonal relations, attempts have been made to diagnose it. One of the most popular tools used in Poland to measure trust towards a partner is the Trust Scale created by Rempel et al. (1985) and adapted to Polish conditions by Wojciszke (2006). It includes three subscales – predictability, dependability, and faith. This three-factor approach to trust assumes that the components of trust are (1) the belief in the predictability of the partner’s behaviour – a necessary condition that makes the person with whom the individual enters into a relationship not arouse fear and distrust; (2) recognition of the partner as a good and trustworthy person, and (3) faith in the attachment of a loved one – the degree of certainty that the partner’s observed behaviour will prove to be a permanent element of the relationship, including in the future.

Larzelere and Huston (1980) proposed the Dyadic Trust Scale. It is a one-dimensional tool used to measure the trust of partners in romantic relationships and marriages. Canadian researchers (Gabbay et al., 2012) adapted this tool justifying its usefulness in the study of homosexual couples. It turned out, however, that it can be adapted to study all kinds of interpersonal relationships; for example, the Turkish adaptation of the Dyadic Trust Scale by Hancer et al. (2008) was adapted to study the trust of hotel employees in relation to managers.

When operationalizing the concept of trust, Larzelere and Huston (1980) referred to two attributes that seem to be particularly important aspects of it – benevolence and honesty of a close person. The benevolence aspect refers to motivation – individualistic (oriented to the profit of one’s partner) or collectivistic (oriented to maximizing common profit). The aspect of honesty, on the other hand, concerns the extent to which a person believes their partner in declarations about future actions and intentions.

It can therefore be concluded that the degree to which a given individual believes in the benevolence and honesty of another person indicates the degree of trust in that person. Dyadic trust, as opposed to general trust, refers to the perceived benevolence and honesty of a particular person considered important (Larzelere & Huston, 1980; Rotter, 1967).

The importance of trust understood in this way for building and maintaining close emotional relationships justifies the desirability of its study also in Poland. This required adaptation of the Dyadic Trust Scale.

PROCEDURE AND PARTICIPANTS

PROCEDURE

The adaptation procedure of the Dyadic Trust Scale (Larzelere & Huston, 1980) included translating the method into Polish and checking the equivalence of both English and Polish versions, as well as verifying the factor structure and determining the psychometric properties of the Polish version of the scale. The translations of the Dyadic Trust Scale from English into Polish, and then from Polish into English, were made by two independent translators. The analysis of the similarity of the English version (the original) and the Polish version allowed both versions to be recognized as equivalent.

The Dyadic Trust Scale (Larzelere & Huston, 1980) is a self-report tool. It concerns the study of people who are in a close relationship. The study participants completed the Dyadic Trust Scale translated into Polish. They were asked to respond to eight statements by marking the selected answer on a seven-point scale (1 – definitely not; 2 – no; 3 – probably not; 4 – neutral; 5 – probably yes; 6 – yes; 7 – definitely yes). The minimum score that can be obtained is 8 points and the maximum is 56 points – the higher the overall score, the higher the trust in the dyad. The inclusion criteria for the study were: 19 years of age and remaining in a heterosexual and lasting emotional relationship for at least 1 year.

The research project received the approval of the University of Lodz Research Ethics Committee (no. 2/KEBN-UŁ/II/2022-23).

PARTICIPANTS

The study was conducted with the participation of 208 people aged 19 to 57 (M = 27.68, SD = 7.29) in close emotional relationships. Most of the respondents were women (n = 167; 80.3%). Among the participants, 20.67% stated that they were married (average relationship length in months: M = 118.21, SD = 96.73), while 79.33% reported being in a cohabitation relationship (average relationship length in months: M = 43.64, SD = 67.23). It was also verified whether the gender of the participants differentiates the level of trust in the study group. For this purpose, Student’s t-test for independent samples was performed. The obtained results are presented in Table 1.

RESULTS

VALIDITY OF THE DYADIC TRUST SCALE

The study group was randomly divided into two equal subsets. Based on the results of the first subset (n = 104), the validity and internal structure of the questionnaire were established. The results of the second subset (n = 104) were used to verify the constructed model using confirmatory factor analysis. SPSS version 28 was used for exploratory factor analysis, and SPSS Amos for confirmatory factor analysis.

STUDY 1

Determining the factor structure of the Dyadic Trust Scale in the Polish group of respondents (N = 104) required exploratory factor analysis – EFA (scree test, principal components analysis, oblimin rotation with Kaiser normalization). In accordance with the original version of the tool and the theoretical premises of the tested construct, an exploratory factor analysis was adopted in a single-factor approach. The results obtained in the EFA, due to the shape of the scree, justified the adoption of such a structure. The absolute value for the coefficients in factor analysis (EFA) was set at 0.5.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used to check the adequacy of the sample selection. The KMO measure of sample selection adequacy was satisfactory (0.86), which means that the internal structure of the analysed tool was clear and reliable (Hutcheson & Sofroniou, 1999). Based on the results of Bartlett’s sphericity test (χ2(28) = 404.70, p < .001), it was concluded that the variance-covariance matrix was not a spherical matrix (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). The values of both measures allowed us to assume that the application of factor analysis to the collected data would be fully correct. Factor loadings for individual items are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Loads of individual factors for the items of the Dyadic Trust Scale in the Polish adaptation

It turned out that the Polish version of the Dyadic Trust Scale includes 5 items (and not 8 as in the original version), which is justified by the substantive analysis of the statistical results. Three items were rejected due to the fact that the absolute value criterion of 0.5 was not met. The minimum score that can be obtained by the respondent is 5 points, the maximum is 35 points – the higher the overall score, the higher the trust in the dyad.

The conducted EFA showed that the sum of factor loadings after extraction explains a total of approximately 55.04% of the common variance.

STUDY 2

In order to verify the fit of the model to the empirical data, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) based on the structural equations model was performed (Byrne, 2010; Kaplan, 2009). The results of the second group of subjects (n = 104) were used for the analysis (using the SPSS Amos program). The model obtained in the exploratory factor analysis was checked. The fit index values for this model are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

CFA results – model fit indices

| Model fit indexes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | NFI | RFI | RMSEA | Hoelter .05 | |

| Model | 13.55 | .001 | 2.71 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.12 | 85 |

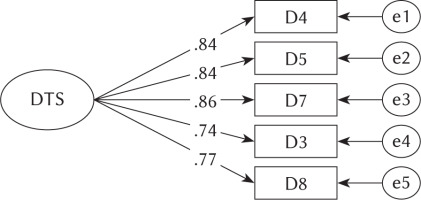

The results suggest that the model is generally an acceptable fit to the data. Despite the chi-square (χ2) test result, which turned out to be significant, and the RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) coefficient, most of the other coefficients (TLI, CFI, NFI, RFI) of the tested model indicate its good fit to the data. When most of the parameters meet the required criteria, the model can be considered acceptable (Tarka, 2017). The resulting model is shown in Figure 1.

In the model presented in the figure, the numbering of the original version was retained in order to show which items were included in the Polish Dyadic Trust Scale.

RELIABILITY OF THE DYADIC TRUST SCALE

The conducted analyses allowed us to obtain a one-dimensional tool consisting of five statements. The Dyadic Trust Scale reliability analysis was performed by assessing the internal consistency of Cronbach’s α, which turned out to be satisfactory. The value of Cronbach’s α coefficient for the entire scale was .89.

CONCLUSIONS

The subject of the article was a presentation of the procedure of Larzelere and Huston’s (1980) Dyadic Trust Scale adaptation. The Dyadic Trust Scale allows for the assessment of trust in a partner with whom the respondent is in a close emotional relationship. The adaptation confirmed the theoretical assumptions made by the authors of the original tool about its one-dimensionality. The original version included eight statements. The factor analysis, conducted based on Polish studies, allowed for the recognition of 5 items. Their interpretation authorizes the understanding of trust (after Larzelere & Huston, 1980) as experiencing benevolence and honesty in a relationship with a partner. The Polish Dyadic Trust Scale turned out to be an accurate and reliable tool. It can be used in scientific research related to diagnosing the trust of Polish partners. The usefulness of this method for the assessment of close relationships justifies the recognition of trust as the key to building and maintaining them.

The conducted research related to the DTS adaptation procedure is not without limitations. The main limitation is the significant predominance of women over men in the study sample. Although the analyses showed that gender does not differentiate trust, this requires however further verification. The model obtained in the CFA turned out to be an acceptable fit to the data, which highlights the necessity to conduct more extensive research and further work related to the adaptation of the tool. It is also important to assess its external validity. In addition, the usefulness of the DTS for diagnosing trust in couples, not just individuals in a close relationship, should be researched. Undoubtedly, the verification of the tool should include the examination of various relationships, e.g. non-heterosexual, consecutive, or long-distance relationships.