BACKGROUND

The social significance of the problem of infertility has become the inspiration to study the challenges faced by families with fertility problems. On the one hand, this is a problem that globally concerns as many as 1 in 6 people trying to conceive (WHO, 2023). Thus, infertility is a global health issue. At the same time, the problem of infertility should also be considered on a local level, as the cultural, political, and worldview determinants are specific to every culture, and coping with the challenges associated with infertility and its treatment are deeply rooted in the socio-cultural environment in which a given couple lives and functions (Malina & Pooley, 2017).

Despite the development of medically assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and their growing efficacy (Dembińska & Malina, 2019), the possibilities offered by contemporary medicine do not resolve the problem of infertility for all the couples having difficulty conceiving. In Poland, where the acceptance of ART is still on a relatively low level, undertaking treatment and sharing information about procreative problems and treatment received is not a natural choice for many couples (Dembińska & Malina, 2019).

A theoretical, empirically verified model of the social infertility cycle model was created based on the results of the author’s own research, with the purpose of analysing the significance of individual and social factors in coping with the challenges of infertility treatment using ART, and addressing the mentioned issues.

SOCIAL ASPECT OF INFERTILITY TREATMENT

SOCIAL ATTITUDES TOWARDS INFERTILITY TREATMENT

Over time, there has been an increasing number of research reports factoring in the social aspects of infertility treatment, including the attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies and their significance for the functioning of couples struggling with infertility (Bowman & Saunders, 1994; Fauser et al., 2019; Fortin & Abele, 2016; Fotopoulou et al., 2015; Genuis et al., 1993; Kovacs et al., 2003).

Attitudes, that is, positive or negative approaches to given concepts, objects or other people, are considered to be relatively fixed and stable over time. This means that attitudes can change in certain circumstances and people will not always behave in line with their original attitudes (Aronson et al., 1997; Wojciszke, 2004). Attitudes are also dependent on objective and sociographic factors, as well as psychological mechanisms.

A systematic analysis of Mendeley and PubMed full-text journal holdings for the keywords “assisted reproductive technology attitudes” revealed 391 entries from 1987 to 2021 (Mendeley) and 1658 entries from 1970 to 2022 (PubMed). The research demonstrates varied support for the utilization of assisted reproductive technologies (Rowland & Ruffin, 1983). However, although a generally high level of support for assisted reproductive technology use was found, controversies persist surrounding various aspects of ART, including donorship and the proliferation of gametes, the removal of unwanted embryos produced through assisted reproductive technologies (Bowman & Saunders, 1994; Genuis et al., 1993; Holmes & Tymstra, 1987; Kazem et al., 1995; Kovacs et al., 1985), public funding of ART, and the use of such methods in mid-adulthood, including among homosexual couples and single men and women (Krastev & Mitev, 2013; Yudin et al., 2012). What is more, the attitudes towards ART use vary depending on the sex of the respondents (men are more supportive of ART) (Schröder et al., 2004) and their age (a much higher acceptance is found among persons under 35 years of age) (Bowman & Saunders, 1994).

The acceptance rates of the assisted reproductive technologies vary depending on the country of origin of the respondents, ranging from 51% of the general population being supportive of it in Nigeria, to 86% in Australia (Kovacs et al., 2003). In Europe, very high ART acceptance rates can be found in Sweden, for example (Wennberg et al., 2016; Westlander et al., 1998). Although it seems that the attitudes towards ART may appear diverse across different countries (Fabamwo & Akinola, 2013), in reality, the control of other cultural factors allows the direct determinants of attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies to be identified. The research suggests that religious affiliation is strongly related to attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies (Bokek-Cohen & Tarabeih, 2022; Genuis et al., 1993; Lessor et al., 1990). For example, the studies indicate that Muslim women are much more willing to use assisted reproductive technologies than Christian women (Milewski & Haug, 2020). Political convictions are also important when it comes to the acceptance of medically assisted reproductive technologies (Fortin & Abele, 2016). Researchers worldwide agree that the cultural context must be taken into account when carrying out research on attitudes relating to ART. The variations between the attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies depending on the cultural context should be taken into account in scientific research, the public debate, and political discourse alike (Haug & Milewski, 2018).

The relevant literature review revealed that healthcare staff are not fully supportive of assisted reproductive technologies (Holmes & Tymstra, 1987; Khalili et al., 2008; Pawa et al., 2020; Svanberg et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the studies cited here show that the attitudes of healthcare workers towards ART use are much more positive than those reported in the general population, which indicates just how important education and knowledge are when shaping such attitudes. Similarly, the findings show that the support for the use of assisted reproductive technologies increases the longer it is used (Kovacs et al., 2003), which may underscore the importance of contact with persons using ART to treat infertility and knowledge built on the basis of contacts with such persons. The significance of knowledge in shaping attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies is particularly emphasised in the context of under-developed countries where knowledge on this topic and attitudes are considered to be directly related (Fabamwo & Akinola, 2013; Olugbenga Bello et al., 2014; Umar & Adamu, 2021).

At this point, it is important to acknowledge that research on the knowledge about assisted reproductive technologies reveals significant deficiencies in this field (Mortensen et al., 2012). For example, studies carried out on a Bulgarian group indicated that although 49% of the respondents valued their knowledge highly, most respondents gave incorrect answers to questions related to ART. Studies carried out on a Portuguese sample, for instance, also revealed poor knowledge of the topic (Macedo et al., 2015). Researchers have emphasised that the age of respondents is of significance for the represented attitudes due to the level of knowledge and contact with couples using assisted reproductive technologies (Fotopoulou et al., 2015; Torres et al., 2013). Both women and men have limited knowledge of the indicators of success of ART, the costs of treatment, and the importance of age when it comes to the possibilities of carrying out assisted reproductive treatment (Szalma & Bitó, 2021).

Another highly important aspect highlighted in the research is the significance of a person’s individual situation and experiences when it comes the formation of opinions concerning assisted reproductive technologies (Schröder et al., 2004). A study carried out in 2019 with a sample of 6,000 respondents from 6 European countries clearly illustrated that despite the high level of overall support and public funding for ART (advocated by 93% of respondents), only 48% of them would be willing to undergo treatment using assisted reproductive technologies should they have fertility-related problems. Over half of the respondents believed that ART encourages many couples to put off parenthood (Fauser et al., 2019). Among the other, clearly negative opinions on assisted reproductive technologies were views that the children conceived in this way are biologically related to only one of the parents due to the donation of gametes (studies on a US sample) (Halman et al., 1992).

According to the above-mentioned studies, the factors that shape attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies include, apart from sociodemographic factors, knowledge, contact, and experiences related with assisted reproduction. One of the studies also points to the significance of persuasive communication in shaping attitudes towards ART, as well as giving support to persons undergoing such treatment. The study of Sigillo et al. (2012) indicated that attention directed at the media can have a direct effect on shaping their attitudes towards the use of ART and may indirectly influence the knowledge of the respondents about assisted reproductive technologies: “The knowledge of the respondents shaped their attitudes and convictions related to assisted reproduction. Furthermore (…) such information can affect an individual’s knowledge and their attitudes towards being supportive of assisted reproduction”. The impact of media and authoritative figures will be discussed in more detail later in the paper.

In Poland, extensive studies on attitudes towards infertility treatment using medically assisted reproductive technologies and the importance of such attitudes when it comes to individual and social functioning of a couple undergoing such treatment are few and far between. Research on the topic is mainly commissioned by research institutes (CBOS, OBOP). It should be noted, however, that the data collection methodology itself does not allow the phenomenon to be fully and comprehensively described from a psychological perspective. Recognizing these limitations, the author of this paper sought to bridge this gap and conducted her own research to address these shortcomings. The study focused specifically on social attitudes towards the use of medically assisted reproductive technologies in Poland and utilized a questionnaire created by the author, consisting of 64 statements (Dembińska & Malina, 2019). Through this research, the author aimed to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological aspects underlying social attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies in Poland.

The mentioned questionnaire measuring attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies was based on the assumptions of the attitude theory (Mika, 1984). The behaviours, emotions, and convictions (behavioural, emotional and cognitive component) that can accompany persons while formulating judgements relating to infertility treatment using assisted reproductive technologies were identified. Then, an independent team of psychologists eliminated the statements that in their opinion were not strictly related to the studied area. The third step involved grouping them into categories by topic (threads) that illustrated the statements. Both positive and negative statements were found throughout these areas.

The identified areas and examples of statements were as follows: the general approach towards ART (The parents of a child conceived by in vitro fertilisation deserve praise for the efforts they put into conceiving a child); the development of children conceived through ART (Children born thanks to in vitro fertilisation may have emotional problems); the family situation (I think that treatment using the IVF procedure has a negative impact on the relationship between the spouses); the social aspect of the treatment (In my opinion, IVF should be available to everyone); own behaviours in the situation of infertility (If I found myself in a situation of infertility, I would have IVF).

The study covered 140 women and 101 men aged 25 to 50 years (the average age of the respondents was 36 years). The results of the study indicated a moderately positive attitude of the respondents towards infertility treatment using assisted reproductive technologies in all the mentioned areas. The most positive approach related to the general attitude to ART and family situation subscale. There was a less positive approach to the development of children conceived using ART subscale and the own behaviours in the situation of infertility subscale, as well as the social aspect of infertility treatment. The study also allowed the identification of statements where the attitude was clearly of a negative nature (I’m irritated by conversations concerning in vitro fertilisation; In my opinion, parents should keep information about their child being conceived through in vitro fertilisation to themselves; I would feel ashamed to admit that my child was conceived through in vitro fertilisation). This tendency was stronger in women than in men (Dembińska & Malina, 2019).

The mentioned results draw attention to the problem of disclosing information about the method of a child’s conception. They reveal an apparent acceptance of the method of assisted reproductive technologies accompanied by a lack of approval of openly talking about infertility treatment. This leads to conclusions concerning the differences in attitudes towards infertility treatment in Poland and throughout the world (Bertarelli Foundation Scientific Board, 2000). Despite the declared acceptance in Poland in the studies commissioned by research institutes being increasingly higher and the level of acceptance approaching world average levels, perhaps it is the social readiness to have open discussions and disclose the methods of conception of a child that constitutes the significant difference, which is difficult to quantify.

CONCEALING INFORMATION ABOUT PROCREATIVE PROBLEMS DUE TO THE CONVICTIONS ABOUT NEGATIVE SOCIAL ATTITUDES TOWARDS INFERTILITY TREATMENT

An important aspect of the social functioning of couples with infertility is the issue of disclosing information about the method of conception of a child. Disclosure is understood as the action consisting of sharing information with others about the difficulties experienced and emotional states related thereto (Dembińska & Malina, 2019; Malina et al., 2019). An essential condition for obtaining support from the broader social environment is sharing information in the sense of disclosing information about the attempts to conceive or the conception of a child using assisted reproductive technologies. Therefore, it is worth taking a closer look not only at the social attitudes that determine the willingness to share information about the method of conception but also at the readiness of Polish couples suffering from infertility problems to disclose such information. The Polish conditions form a specific backdrop for couples considering using ART and sharing such decisions with others. On the one hand, the experience of infertility itself carries with it a crisis and psychological costs of coping with it (Dembińska, 2014) while, on the other hand, it is so stigmatised in the public debate, supported by the voices of Catholic circles, that such a choice may become an additional psychological burden (Dembińska, 2018).

It turns out that both the representatives of the general population and healthcare practitioners worldwide disagree about the validity of disclosing information about the way a child is conceived. It is also pointed out that the non-disclosure of information about the method of conception of a child may limit the ability of persons with infertility to talk about their own thoughts, feelings, and experiences related to their infertility problem (Milsom & Bergman, 1982; Svanberg et al., 2008). Research conducted across the world addresses the problem of disclosure of the method of conception from the parents’ perspective. Analyses carried out in England (Peters et al., 2005) show that most of the studied parents shared information about going through in vitro fertilisation (IVF) with someone else, usually with a close friend or relative. 26% of mothers and 17% of fathers talked about it with their children, and close to 60% of parents said that they had had such a conversation in the past. The researchers also noted that the absence of initiative to disclose the method of conception is explained by a low significance of such information and the desire to “protect” the child against potentially unpleasant experiences (Ludwig et al., 2008). Other researchers (Tallandini et al., 2016) point out that some of the not-disclosing parents indicate the risk of their children being stigmatised for potential health risks (the conviction of there being a risk of genetic diseases and unintentional kinship) as a reason for this. It is also worth adding that when parents presented a restrictive approach to privacy and information sharing, a negative impact of this was found in relation to the quality of their relationship with their children (Rueter et al., 2016).

To support the thesis of a social aversion to disclosing information about the method of conception of a child among Poles, Dembińska and Malina (2019) carried out research where the representatives of the general population were asked the following question: Should parents of children conceived through in vitro fertilisation also disclose information about this fact to society? After analysing the responses of the participants who took part in the study, the author concluded that the vast majority of the respondents stated a clear aversion to disclosing information about the method of conception. Their rationale for such a decision is that it is not important, it bears no impact on society, and that these are the personal matters of the parents. An example of a statement from this category is: No, because the method of conception of offspring does not affect the child or the milieu. Apart from that, these are the intimate matters of the parents of the conceived child. Some of the respondents leave the issue of disclosing the fact that assisted reproductive technologies were used to the discretion of the parents. For example, one response was: Not necessarily, unless they want to. I think it’s irrelevant for others. The convictions of couples concerning attitudes towards infertility and its treatment are based on the observations of the social context.

The author’s own research, which involved 52 infertile couples (focus groups), indicates that there are differences between women and men concerning the willingness to disclose information about starting treatment. The findings show that women highlighted the compassion shown to them by other women. Men, on the other hand, mention the frequent belittling of the problem by other men in their social context. Out of all the respondents, only four couples out of all the respondents stated that they had no bad experiences related to disclosing information about the infertility process they underwent. However, the majority did not disclose any information about the undertaken infertility treatment due to fear of their actions being judged or of being an “unhealthy sensation” (If our parents knew, they would really start to worry and ask questions; Our family lives in the town where we go for treatment and we’re always worried about bumping into someone we know).

Based on the mentioned studies, it can be assumed that in Poland, considering the awareness of social reluctance to openly speak about infertility treatment, couples may decide to conceal information about their infertility problems and the methods used in its treatment more often. Why is it so important?

DISCLOSURE AS A POTENTIAL SOURCE OF KNOWLEDGE ABOUT INFERTILITY TREATMENT AND CONTACT. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF KNOWLEDGE AND CONTACT IN SHAPING AND SUSTAINING ATTITUDES TOWARDS MEDICALLY ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGIES

Polish society is characterised by relatively traditional values and beliefs (Evason, 2017). The main social role of a Polish woman and the most important function of a family is the bringing up of children. The Catholic Church is considered the dominant organisation influencing public opinion, including through the media (Haidt & Kesebir, 2010; Jarmakowski-Kostrzanowski & Jarmakowska-Kostrzanowska, 2016). According to sociologists, attitudes to infertility are associated with poor knowledge and moral judgements (Vogel & Wanke, 2016; Wahl et al., 2012), and therefore can be shaped be means of media messages. Earlier studies identified several predictors of attitudes towards controversial social issues and/or minority groups (e.g., sexuality or climate change), some of which include knowing a person who belongs to a minority group or has unpopular convictions (Haidt & Kesebir, 2010).

The studies of psychologists highlight the significance of moral codes and knowledge about assisted reproductive technologies in shaping attitudes towards persons using ART as a method of infertility treatment (Malina et al., 2021). In the study that was carried out, attitudes towards persons who had in vitro fertilisation were diagnosed because attitudes can predict actions towards the object of the attitude (e.g., stigmatisation and discrimination vs acceptance and caregiving). The study focused particularly on women because, in so much as infertility treatment concerns the couple as a whole, it is mainly women who are identified with infertility treatment in Poland (Dembińska, 2012, 2014; Domar et al., 1992). This is particularly so as, according to medical data (Ruchała & Sawicka-Gutaj, 2016) and public opinion, the assessment of the reproductive capacity of women is key to achieving pregnancy (Ruchała & Sawicka-Gutaj, 2016). The factors that were taken into consideration as potential predictors of shaping attitudes towards persons receiving IVF as a method of infertility treatment were: the role of contact with someone who had already undergone an in vitro fertilisation procedure (behavioural component), moral codes (emotional component), and knowledge about in vitro fertilisation (cognitive component). A total of 817 respondents (692 women and 118 men) aged between 18 and 60 years (M = 26.00, SD = 8.00) took part in the study. The attitude towards a woman receiving IVF as infertility treatment was studied using the modified social distance scale by Bogardus (1933). The results of the research indicate that knowing a person who had undergone IVF is a weak predictor of attitudes towards women who had IVF. Three moral codes were demonstrated to be important: caregiving/harm and justice/fraud as the positive predictors of attitudes towards a woman receiving IVF; and sanctity/degradation as the negative predictor. A higher result in the test on IVF knowledge was a positive predictor of attitudes towards women who had had an IVF procedure. At the same time, the respondents who knew a person who had already undergone IVF were characterised by a higher level of knowledge about the procedure. It may, therefore, be surmised that knowledge resulting from having contact with a person who had previously undergone infertility treatment is conducive to having a positive attitude to couples treated for infertility. What is more, contact with a person receiving infertility treatment and access to knowledge about the given method of infertility treatment are conditioned by the couple disclosing information about undergoing infertility treatment. It is widely recognised that such contact leads to a reduction in the level of prejudices and to an improvement of overall inter-group relationships (Hofmann & Schmitt, 2008; Weishut, 2000). For example, studies indicate that the level of personal experience (behaviour) with the object of the attitude and the significance and availability of the object of the attitude affect the development of an attitude and allow the impact of the attitude on behaviour to be predicted (Haidt, 2001). It can, therefore, be conjectured that the absence of any experience with the object of the attitude may result in negative attitudes towards persons undergoing in vitro fertilisation procedures (Malina et al., 2021).

It is worth emphasising that, in the Polish context, the absence of contact with persons suffering from infertility and limited access to knowledge go hand in hand with maintaining the false convictions presented in the media by authoritative figures. On the one hand, obedience to authority figures releases a person from responsibility for the decisions being taken, but, on the other hand, mindless submission may carry negative social consequences (Doliński, 2000; Hamer, 2005; Myers, 2003; Wojciszke, 2004). The behaviour of an individual under the influence of an authority figure is affected not so much by their personal disposition but by the situation, particularly if it is new, vague and extraordinary (Doliński & Grzyb, 2017). This is confirmed by several research studies. For example, a study conducted by the author, along with Barancewicz and Dąbrowska (Malina et al., 2022), underscored the significance of authority in shaping and maintaining attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies. The research involved the participation of 359 individuals aged between 16 and 65 years, with a mean age of 27.47. The group was dominated by women, with a total of 300 (83.57%), while men constituted the minority, totalling 59 (16.43%). The experimental method involving an independent group design was used in the study. In the control group, the respondents were presented with 15 statements concerning assisted reproductive technologies, 3 of which (non-diagnostic) were true. The remaining statements were false. The respondent was tasked with identifying which of the presented statements were, in their opinion, true, marking true or false on the sheet provided. In the experimental group, the same statements were preceded by information that they were the statements of a fictitious authority figure, for instance: “Rev. Pinkowski claims that…”; “Professor Lamparski believes that…”. The study pointed to the significance of an authoritarian message in maintaining attitudes towards assisted reproductive technologies in small towns in Poland. The residents of small towns from the experimental group were influenced by authority figures to a greater extent than the inhabitants of large cities from the control group (Malina et al., 2022). The results obtained may indicate a greater importance of authority figures in small local communities, which is in line with the reports that the smaller the social context, the greater the significance and acceptance of authority figures as these are usually individual authority figures (not institutions), who are also often known personally in such societies (Tuziak, 2010) and the inhabitants of smaller towns having limited access to knowledge. This is because they may not experience the same frequency of contacts with persons undergoing infertility treatment as those living in larger agglomerations. Considering that, according to the Central Statistical Office of Poland (GUS, 2023), almost 3/4 of the population of Poland lives in small towns and villages, it seems that increasing the awareness of the residents of these areas may be critical to shaping the general social approaches to assisted reproduction technologies.

The analyses carried out indicate that, in the Polish context, there is cyclicality of behaviours of persons with infertility using assisted reproduction technologies. On the one hand, we are objectively dealing with a population in which it can be said there is a relatively low acceptance of openly talking about infertility. On the other hand, however, the lack of open discussions may lead to limited knowledge and the reinforcement of certain views by authority figures, thereby strengthening the negative attitudes resulting from limited knowledge. However, in light of the foregoing, couples may also have limited access to social support. An analysis of this aspect is presented below.

THE INDIVIDUAL ASPECT OF INFERTILITY TREATMENT

SOCIAL SUPPORT IN INFERTILITY TREATMENT

As already mentioned above, couples are reluctant to disclose information about undergoing assisted reproduction technology treatment. This may be caused by a strong sense of social pressure and mismatch. At the same time, withholding information about the undertaken treatment blocks the possibilities of obtaining support and may exacerbate the sense of isolation. Couples feel insufficient support and if it is being provided, it is usually only from their partner. Such a situation may lead to secondary problems with fertility caused by elevated levels of procreative stress. As has been reported by researchers, seeking support is of great importance for the quality of partner relationships, as well as for the individual development of the partners. In an infertility treatment setting, the partner is often an insufficient source of support since they themselves are experiencing difficulties resulting from the procedures that are involved in medically assisted reproduction technologies (Abbey et al., 1995; Boivin et al., 1999). This implies that additional support channels and sources are necessary to establish.

Infertility may be a stressful situation for a person experiencing it, which may also take the form of a crisis (Holas et al., 2002). One of the characteristic traits of a crisis is the temporary incapacity to fight the crisis using the means that the individual has used so far in difficult situations (Hoff et al., 2009). Successful navigation through a crisis largely depends on intervening persons and social support provided by them. Social support reduces the level of experienced stress as well as the further negative effects of stress (Cobb, 1976; Dudek & Koniarek, 2003; Koss et al., 2014; McNaughton-Cassill et al., 2000; Ying et al., 2015). The conducted analyses allowed the source of support available to infertile couples to be systematised and included the following:

Partner-partner support – in a situation of infertility, support may be insufficient in many cases as both partners need support (Koss et al., 2014; Ying et al., 2015).

Institutional support (individual or couples psychotherapy) – couples benefiting from it report a higher life satisfaction, acceptance of their infertility, and lower anxiety (Eugster & Vingerhoets, 1999; Fauser et al., 2019; Keramat et al., 2014; Martins et al., 2011).

Informal support groups – couples state that they feel less stressed and highlight the importance of social bonds when they are part of an informal support group (McNaughton-Cassill et al., 2000, 2002). According to some researchers, advice and support groups seem to be the most effective psychosocial interventions in infertility (Wischmann, 2008).

The author’s own study in the form of focus groups carried out with the participation of 52 infertile persons (26 women and 26 men) confirmed that couples feel they are given insufficient support and the support provided is usually only from their partner. This can lead to secondary fertility problems caused by increased reproductive stress.

On the other hand, couples admit that once they do get to share their emotions and obtain support, this improves their mood and well-being (Malina & Szmaus-Jackowska, 2021). All the respondents, regardless of their sex, indicated their partner as the person from whom they get most support. Half of the studied couples mentioned family members (parents, siblings) among those who give them support, both emotional and financial. Two couples mentioned so-called “silent support” of their family (“they know about our problem, but thankfully they don’t ask about anything”; “they never bring it up”). Three couples spoke of significant emotional support received from close friends who often had similar experiences (“we have a couple who we’re friends with, they have two children conceived through IVF and they’re very much rooting for us”). It is also worth pointing out that many women participating in the study indicated that they found online forums dealing with the topic supportive, as there they can regularly meet other women with similar problems. To conclude, failing to disclose information about undertaken infertility treatment attempts is connected with limited access to social support. This in turn may consequently be associated with the experience of stress and the generation of secondary reproductive problems.

SIGNIFICANCE FOR SUCCESSFUL OUTCOMES OF SUPPORTIVE SOCIAL INTERACTIONS IN THE INFERTILITY TREATMENT PROCESS

Supportive social interactions (Malina et al., 2019) have been suggested as a key form of received social support, and their effectiveness in terms of the couple’s well-being and impact on the results of infertility treatment was verified in the author’s subsequent study. A supportive social interaction was defined by the author as: a group interaction involving talking or listening in an informal and non-judgemental environment which leads to the reduction of stress.

The significance of support in mitigating stress symptoms and the role of stress hormones in achieving successful reproductive outcomes underscores the relevance of a scientific and interdisciplinary approach to addressing this issue. In addition, exploring the efficacy of informal support groups in comparison to formalized psychotherapy as a means of support, and conducting analyses in this domain, represents an underexplored area within the realm of Polish infertility research.

In relation to the above, the subject of the project implemented under the “Miniatura NCN” programme (project no. 2017/01/X/HS6/01896) was the analysis of the meaning of supportive social interactions in the infertility treatment process for the effectiveness of infertility treatment. The aim was to study the impact of non-institutionalised support on the level of stress hormones. Cortisol was selected as the biomarker related to the body’s response to a stressful situation, as an elevated level of cortisol, linked to prolonged stress, may lead to erectile dysfunction or ovulation and menstrual cycle disorders. Furthermore, androgen sex hormones are produced in the same glands as cortisol; hence, the excessive production of cortisol may hinder the optimal production of these sex hormones (Weinstein, 2004). A stressful experience and elevated cortisol levels contribute to the overall deterioration of psychological functioning and may have a negative impact on somatic health (Richman, 2005), thereby reducing the chances of achieving pregnancy (Galst, 2017). This results from the fact that immunological processes are sensitive to the action of emotions (Knapp et al., 1992).

The experimental study was carried out in two independent groups. The study included 51 heterosexual couples who were candidates for the in vitro fertilisation procedure. The first stage of the research procedure, which was conducted with the participation of couples from both groups (experimental and control groups), included the collection of saliva samples to obtain information about the stress levels (cortisol concentration analysis). Information on the subjectively felt stress was also collected. At the second stage of the experiment (immediately after the collection of samples from all the participants), the couples from the control group watched a 150-minute film about human embryology (a non-emotional factor). At the same time, the persons from the experimental group took part in a supportive social interaction. The interaction was always carried out in a group of 5-6 couples. The psychologist who moderated the discussion did not get involved in the discussion itself. The participants were encouraged but not forced to engage in the communication. They spoke spontaneously, one by one. The interaction was in line with the needs of the participating group members. Once the experimental and control conditions had been introduced, another saliva sample was collected from all the respondents (stage three). Information about the infertility treatment history was obtained and questionnaires concerning the psychological characteristics of the respondents were handed out.

The obtained results revealed that the drop in cortisol levels in the saliva was higher in the experimental group than in the control group, both in women and in men. The average decline observed in women was slightly higher than in the group of men. The study proved the significance for successful outcomes of supportive social interactions in the couple infertility treatment process involving ART. The use of biomarkers ensured greater objectivity than self-descriptive questionnaires and enabled an analysis of the significance of support for the somatic health and reproductive success of the couple. The study also brought the problem of sharing reproductive struggles to the fore, which, as mentioned earlier, many Polish couples face. This is because the ability to get involved in supportive social interactions gives the couples an opportunity for broader disclosure.

SOCIAL INFERTILITY CYCLE MODEL

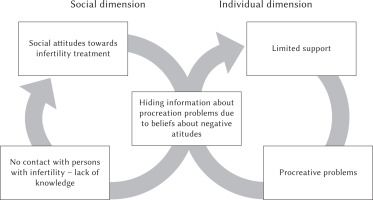

All the author’s own studies carried out and described herein contributed to the creation of the social infertility cycle model (Figure 1). The model presented hereunder may be characterised by actions (behaviours) and factors that are associated with the occurrence of these behaviours (Table 1). It takes two perspectives into account: the social and individual.

Table 1

Actions (behaviours) and factors related to the occurrence of these behaviours in the in the individual area of infertility treatment and social dimension

The social infertility cycle model assumes that persons with infertility, due to their own beliefs concerning the attitudes of the general population to infertility, are unwilling to share information about the treatment undertaken and its effects with the social environment. Thus, access to knowledge regarding the prevalence of infertility problems and the available methods of infertility treatment is crucial. In turn, the lack of knowledge reinforces the negative attitudes of the social environment towards infertility treatment (social aspect). On the other hand, the limited sharing by treated couples blocks access to information about this to their closest milieu, which is linked to limitations in terms of seeking and obtaining support. The inadequate social support leads to higher stress and anxiety, which may then have a rebound effect on the reproductive capacity of the couple (individual aspect).

CONTEXTUALITY OF INFERTILITY TREATMENT

The inspiration behind undertaking the research in the field of family development in an infertility setting was the social significance of the problem of infertility and the necessity to address the challenges and implications associated with infertility.

The observation of social life and demographic data indicate that an increasing percentage of young Poles are struggling with reproductive problems. Changes in the value system of young Poles related to the promotion of the development of independence and the liberalisation of the model of the family are leading to delaying the decision to conceive. The natural environment is also changing to the detriment of the family. Both stress related to the pace of contemporary life and the external changes accompanying it concerning the quality of the food resources, or climate change, can have a negative impact on the reproductive capacity of the partners.

The proposed social infertility cycle model was created on the basis of several studies carried out over 2015-2021. The aims of the conducted studies were: (1) systematising knowledge on the functioning of infertile persons in Poland; (2) analysing social attitudes towards persons using medically assisted reproductive technologies and attitudes towards disclosing the method of conception of a child; (3) analysing the sources of social attitudes towards methods of assisted reproductive technology; (4) analysing the mechanisms for maintaining and changing social attitudes towards the use of assisted reproductive technology methods; (5) analysing the significance and sources of support in the process of treating infertility; (6) analysing the significance of supportive social interactions in the infertility treatment process for the effectiveness of infertility treatment. The studies involving the general population and persons with infertility were mainly quantitative in nature.

The presented social infertility cycle model can be used to create social policy and support programmes intended for couples with infertility. Spreading awareness on infertility treatment with ART, combating myths and disseminating reliable knowledge should lead to an improvement in the social situation of infertile people. The model helps to understand that knowledge about infertility can be conducive to inducing positive attitudes towards infertile couples. At the same time, strengthening positive attitudes could encourage people with infertility to be ready to talk and reveal their procreative problems, which, according to the proposed model, may increase their chances of obtaining support and thus the chances of getting pregnant. Therefore, the model can be used both in individual work with a patient (psychoeducation in terms of the importance of sharing) and in creating social policy programmes (in terms of increasing knowledge). The model seems to be useful in other cultural contexts, as it points to the fundamental importance of knowledge.

In further research, it is worth looking more closely at the effect of authority on shaping public opinion on assisted reproduction. It is also worth considering the importance of the long-term impact of supportive social interactions and pointing out in which cases supportive social interactions are an insufficient source of support and the support of specialists in the field of psychological help should be sought.

Despite the growing support for medically assisted reproductive technology use, both in Poland and across the world, there is evidence that we still experience the social stigma of infertility among infertile couples (Franklin, 2013). Young people undertaking infertility treatment often keep this information to themselves, not even sharing it with their closest family. This is because infertility treatment is enmeshed in religious, political, financial, and legal contexts. For example, despite the fact that in vitro fertilisation has been available in Poland for 25 years, society is still divided in terms of the opinions about couples with infertility using medically assisted reproductive technologies due to the high socio-economic and educational diversity of the society. In Poland, the overall acceptance of society concerning the use of assisted reproductive technologies by infertile couples has increased from 60% in 2008 to 76% in 2015, and is still continuing to gain supporters (CBOS, 2015). Comparatively, social support in Western Europe for the use of assisted reproductive technologies is as high as 93% (Fauser et al., 2019). These findings indicate that, although Poland has shown a positive trend over the years, there is room for further improvement and continued efforts to raise awareness, promote understanding, and foster a more supportive environment for couples utilizing medically assisted reproductive technologies in Poland.

Infertility constitutes a serious emotional crisis that is connected with the loss of self-worth, elevated levels of experienced stress, and low mood (Dembińska, 2012; Domar et al., 1992), and often is also associated with the loss of a sense of being physically attractive, of trust towards one’s partner, of self-confidence, and of a sense of security (Łuczak-Wawrzyniak & Pisarski, 1997). Numerous studies have revealed that infertility is related to lower satisfaction with sexual life and with the relationship with one’s partner (Bączkowski et al., 2007; Ferraresi et al., 2013; Perkins, 2006). The mechanisms of psychological adjustment of couples struggling with the problem of infertility are disrupted (Łuczak-Wawrzyniak & Pisarski, 1997).

The growing scale of the phenomenon of infertility, the psychological difficulties resulting from infertility treatment, and the increasing use of medically assisted reproductive technologies indicate that there is an area where psychological knowledge seems to be particularly important. At the same time, this is a highly delicate problem; hence, it is not always easy to lead an open dialogue in this area. Thus, there is a need to find ways of supporting couples dealing with an infertility crisis. This is the source of a huge psychological burden for the whole population of young adults. In Poland, scientific research on infertility treatment focuses on the medical aspects of carrying out infertility treatment procedures. The issue of legal regulations and bioethical issues are discussed and deliberated on but the issue of the psychosocial consequences of infertility treatment is not widely taken up in Polish scientific literature. Instead, studies tend to concern the situation of infertility itself. However, there is a lack of detailed data concerning the psychological aspects related to undertaking infertility treatment attempts using medically assisted reproduction technology methods (Bielawska-Batorowicz, 2006). Infertility treatment is also impacted by the social context since the public debate is eagerly joined by politicians, with church officials additionally adding to the already highly strung atmosphere. That is why it is particularly important to have a balanced debate on infertility that is supported by scientific arguments and for government and non-government assistance programmes to be based on scientific findings.