BACKGROUND

FAMILY WITH A DISABLED CHILD

The presence of a disabled child affects the family life in many aspects. Firstly, it disrupts the existing family system, and adds new responsibilities to family members. Furthermore, it affects the living space of the family, relationships between parents and siblings, but also family routines and family socialization, expectations, plans, parents’ work-life and family finances (Aydogan & Kizildag, 2017; Buchholz, 2023; Cuzzocrea et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2016). Therefore, this disturbed family system may frustrate the needs of its individual members and limit their individual development, but also the development of the family as a system (Burke & Montgomery, 2000; Cuzzocrea et al., 2013; Marat, 2015).

However, the current studies on the functioning of families with a disabled child provide very interesting conclusions, showing that it is also associated with many positive and enriching experiences (Burke, 2004; Pisula, 2007; Yoo & Lee, 2023). The presence of the disabled family member can have a positive effect on the development of the family system by supporting the development of mutual support of all family members, family cohesion, and also a stronger bond between parent and children, and siblings as well (Durà-Vilà et al., 2010; Green, 2007; Penner, 2020; Zhang et al., 2013).

FUNCTIONING OF A HEALTHY CHILD WITH A DISABLED SIBLING

Despite some evidence in the research for general trends in relationships between a disabled child and his/her typically developing sibling, the findings are mixed (Burke, 2004; Caliendo et al., 2020; Cuskelly et al., 2023; Knecht et al., 2015; Milevsky & Singer, 2022; Perenc & Pęczkowski, 2018; Takataya et al., 2019). The experiences gained in relations with a brother or sister during everyday activities, including playing together or developing conflict solving skills, influence social relations, personality growth and coping strategies of the child (Giallo et al., 2014; Woodgate et al., 2016).

Adolescents have more cognitive capacity to understand the sibling’s disability and presented symptoms, as well as a higher ability to help parents in taking care of sick siblings (Ferraioli & Harris, 2009); thus they often may be identified as “young carers” (Burke, 2004). Taking too much time taking care of a disabled sibling and engaging in doing housework are often an additional responsibility that a healthy child must take on, which may result in emotional problems, or even maladjustment (Mandleco & Webb, 2015; Takataya et al., 2019). These expectations also make it necessary for a healthy child to mature more quickly than would be the case if they did not have a disabled sibling (Burke, 2004). Research also indicates that adolescent siblings of a disabled child exhibit higher levels of depression, anxiety, and other internalizing behaviors (Caliendo et al., 2020; Lovell & Wetherell, 2016), as well as externalizing behaviors (Burke, 2004; Stephenson et al., 2017). A growing body of research also suggests that siblings of disabled children are bullied at school and have difficulties in relations with peers (Becker & Sempik, 2019; Pit-Ten Cate & Loots, 2000).

On the other hand, previous studies have shown that having a disabled sibling may also have many positive outcomes. Siblings of children with Down syndrome present more empathy and kindness than siblings of children without any disability (Cuskelly & Gunn, 2003; Roper et al., 2014). Furthermore, an increase in self-esteem, sincerity, self-control and more helping behaviors are also reported in siblings of disabled children (Kaminsky & Dewey, 2001; Takataya et al., 2019). They also may experience positive feelings – satisfaction and pride according to helping the family to take care of a disabled sibling (Pilowsky et al., 2004), higher tolerance and understanding (Mulroy et al., 2008).

RATIONALE OF THE STUDY

Current scientific research on the functioning of families with a disabled child has focused mainly on relations with parents, parental roles, teachers, and medical staff surrounding the disabled child. The role of siblings has been limited, although there has been an increase in research in this area in the last decade (Takataya et al., 2019).

Furthermore, little is known about the functioning of adolescents with disabled children – most of the studies concern younger developmental stages than adolescence (Ünal & Baran, 2011; Vella Gera et al., 2021), and older ones – such as relationships in adulthood (Dew et al., 2014; Malviya, 2018). The adolescence period is often omitted and developmental tasks characteristic of this stage, such as undergoing an adolescent crisis, are not included in the research, focusing on variables such as empathy or coping with stress (Çelik et al., 2018; Feinberg et al., 2003).

Moreover, relatively little research concerns siblings of children with various types of disability (Roper et al., 2014). Most of them focus on study of siblings of children of one type of disability (mainly autism spectrum disorder or Down’s syndrome), compared to the sibling group of healthy children (Hodapp & Urbano, 2007; Lovell & Wetherell, 2016). Therefore, it seems important to address the issue of the functioning of siblings of disabled children in the broader context of disabilities.

OBJECTIVES

Primary objectives. The primary aim of the project is to investigate the specificity of the growing up process in adolescents having disabled siblings. The functioning of a healthy adolescent as a person growing up in three environments will be examined: family, peers and school. Thus, the following research questions were formulated:

Does having a disabled sibling influence the functioning of a healthy child in the family system?

Do siblings of disabled children show a higher level of maturity than their peers with properly developing siblings?

Does having a disabled sibling modify a child's functioning among peers?

Does having a disabled sibling modify healthy adolescent's educational experience?

Is there a greater risk of psychological disorders among siblings of disabled children than among siblings of normally developing children?

Secondary objectives. The secondary objectives of this study are analysis of the role of sibling’s disability type for the healthy child’s functioning in the family system, as well as moderation effects of gender and the level of parentification on healthy adolescents’ educational success. Furthermore, possible moderation effects of gender on the risk of psychological disorders (internalizing and externalizing) among siblings of disabled children will also be examined.

STUDY REGISTRATION

The protocol of this study has been registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/, registration number: NCT06156124.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

STUDY DESIGN

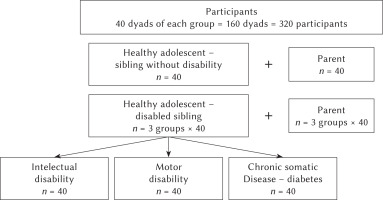

This will be a cross-sectional case-control study conducted in Poland. A total of 160 dyads (320 participants) – an adolescent and one of his/her parents – will take part in the study. Figure 1 presents the particular groups of the study participants. Half of the boys and girls should be in each group (20 girls, 20 boys) to investigate the gender differences in the occurrence of disorders according to the objectives.

STUDY SETTING

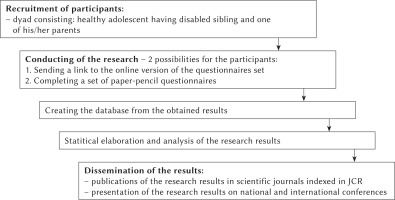

The research will be conducted in two ways: 1) by sending a link to the online version of the questionnaires to the recruited participants (dyad: healthy adolescent and parent) – participants will use their own electronic devices, e.g. mobile phones, laptops, tablets, to complete the questionnaires, or 2) by completing a set of paper-pencil questionnaires which will be provided to the participants personally by the principal investigator of the study. The use of the above two options will make it possible to reach participants from different places in the country, as well as encourage young people to take part in the project, as nowadays they are more willing to fill in online questionnaires than in the paper-pencil version. Figure 2 presents a diagram of the research plan.

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the particular study groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study groups

OUTCOMES

Information regarding functioning in the family with disabled sibling, relations with peers, functioning at school and the growing up trajectory will be collected from adolescents, while information regarding clinical problems will be provided by their parent.

Adolescent’s functioning in the family with a disabled sibling

Sibling relations. To assess the quality of the relationship between a healthy adolescent and his/hers siblings, the Questionnaire of Relationships with Siblings (Lewandowska-Walter et al., 2016) will be used. The above questionnaire consists of 20 items, composed of three subscales: 1) cohesion, 2) communication, 3) rivalry.

Parental attitudes. To measure the perception of parental attitudes among adolescents, the Parental Attitude Scale-2 (SPR-2; Plopa, 2012) will be used. The questionnaire enables the evaluation of five parental attitudes: acceptance-rejection, demanding, autonomy, inconsistency, and overprotective. The questionnaire consists of 45 items (separately for mother and father).

Relations with peers

Relationships with peers will be assessed on the basis of the answers given to the questions in the survey created for the purposes of the study. The questions will consider issues such as: amount of time spent with peers: “On average, how many hours per week do you spend with your peers (friends) outside school time?”; number of close friends: “How many close friends do you have?”; participation in joint activities with peers: “Does having disabled siblings make your friends less willing to spend time with you and exclude you from joint activities?”, “If so, how often do you experience such things?”.

Furthermore, to investigate the adolescents’ quality of life in terms of relationship with peers and support from them, the Polish adaptation of KidScreen-27 will be used (Mazur et al., 2008). This health-related quality of life questionnaire consists of 27 items and measures five dimensions of quality of life – the social support and peers dimension will be used in the research.

Functioning at school

As previously, functioning at school will be assessed on the basis of the answers given to the questions in the survey created for the purposes of the study. The questions will consider issues such as: school achievement: “What was your arithmetic mean grade obtained in all the subjects at the end of the former school year?” (the arithmetic mean grade is reported for students on the yearly certificate of class completion; in our study it will be self-reported by the adolescents); extracurricular activities: “Do you participate in any extracurricular activities (interest clubs, tutoring, sports)?”; “If so, how many extra-curricular activities do you participate in (enter the number)?”; “List what the activities are (e.g. soccer, dancing, etc.)”.

Moreover, the Polish adaptation of KidScreen-27 will be used (Mazur et al., 2008) to investigate adolescents’ quality of life in the school environment dimension.

Growing up trajectory

Parentification. To measure the level of parentification in adolescents in our research, the Parentification Questionnaire for Youth (PQY; Borchet et al., 2020) will be used. The PQY consists of 26 items. The scale is composed of four subscales: 1) emotional parentification toward parents, 2) instrumental parentification toward parents, 3) sense of injustice, and 4) satisfaction with the role; and additionally two subscales for adolescents who have siblings: 1) instrumental parentification toward siblings, and 2) emotional parentification toward siblings.

Adolescent crisis. We will use parts I and II of the Teenage Rebellion Questionnaire (Oleszkowicz, 2001, 2006) to assess one of the manifestations of the adolescent crisis – teenage rebellion. Part I describes 39 situations in which teenagers may rebel. These situations refer to three triggers (limitations, threats or discrepancies) and contain a description of a specific subject of rebellion. Part II of the questionnaire contains descriptions relating to four subject groups: 1) behaviors that are a manifestation of rebellion and the reasons for refraining from manifesting rebellion outside; 2) the judgments underlying the rebellion, which were assigned through theoretical analysis to three mechanisms of rebellion: a sense of restriction, a sense of threat and a sense of discrepancy; 3) emotions related to rebellion; and 4) indicators on the basis of which adolescents distinguish rebellion from other mental states.

Clinical problems

To assess the possible clinical problems in adolescents with disabled siblings, which may indicate a disturbed trajectory of the growing up process, the Child Behavior Checklist 6-18 (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), which will be completed by one of the parents, will be used. The CBCL is a widely known parent measure of emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents, consisting of 113 items and several scales, which are arranged hierarchically. At the top of this hierarchy are the Internalizing Domain and the Externalizing Domain. The Internalizing Domain includes three narrower scales of syndromes, 1) Anxious/Depressed, 2) Withdrawn/Depressed, and 3) Somatic Complaints, whereas the Externalizing Domain includes 1) Rule Breaking Behavior and 2) Aggressive Behavior syndrome scales.

All adolescents and their parents will respond to questions about sociodemographic variables, such as sex, age, place of residence, school, class, parents’ education level and work, as well as questions regarding the number of siblings (brothers and sisters separately), their age and the type of disability.

SAMPLE SIZE

Participants of this study will be recruited by purposive sampling. Based on a-priori power analyses using G*Power 3.1.9.4 software it was calculated that the study group should include a minimum of 35 dyads of each group, with power set to .80 and expected effect size of f = 0.25. Therefore, in order to take missing data and drop-out into account, at least 40 dyads of each group will be recruited. In order to minimize the possibility of dropping out, participants will receive a voucher of PLN 100 per dyad, after both the adolescent and his parent have completed the questionnaires.

RECRUITMENT

Study participants will be recruited in educational institutions, psychological and pedagogical counseling centers, hospitals, therapeutic centers, as well as through advertisements in social media.

DATA COLLECTION

Only new data obtained in the research process will be used. Data will be obtained from participants in two ways:

Online version of battery of questionnaires via research panel – using the participants’ own electronic devices, e.g. mobile phones, laptops.

Paper-and-pencil battery of questionnaires prepared and provided personally by project principal investigator – completed in the places of everyday functioning of the participants (e.g. schools). In the next stages, data from paper questionnaires will be digitalized.

DATA MANAGEMENT AND CONFIDENTIALITY

Each participant will be assigned a unique code. Parent and child will be assigned codes whereby it will be possible to combine their data for data analysis. All data from the questionnaires will be entered into a Microsoft Excel database and copied to a database in IBM SPSS Statistics-26 or the R environment. Copies of created databases will be stored on a password-protected laptop and external SSD disk. Paper questionnaires with original data will be stored in binders with a code and kept locked. Furthermore, Microsoft OneDrive Cloud, encrypted and licenced only for University of Gdansk students and employees, will also be used. Data copies will be created weekly on the selected devices automatically and continuously on Microsoft OneDrive Cloud. Project data will be archived at the proper time after the end of the project in accordance with the University of Gdansk guidelines.

The obtained data will be monitored and evaluated carefully by the principle investigator during the project duration. All doubts regarding the quality of the collected data will also be regularly consulted with the project supervisor. Moreover, the data will also be analyzed in case of outliers and missing data. In the online version of the questionnaires, the option of having to answer each question will be set, while in the case of a set of questionnaires completed in the paper-and-pencil version, the questionnaire will be checked by the principal investigator immediately after completion by the study participant in order to check whether any question has been omitted by the respondent.

DATA ANALYSIS

The obtained data will be analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics-26 and the R environment. In the proposed research the correlation model, regression analyses, as well as ANOVA, mediation analyses and structural modeling will be conducted, in order to verify the research questions and hypotheses. Furthermore, the measures of statistical dispersion and location will also be determined, as well as other calculations, if necessary.

ETHICS AND DISSEMINATION

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Board for Research Projects at the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Gdansk, Poland (decision no. 06/2022).

The protocol will be disseminated primarily through recruited psychology student collaborators and the principal investigator. Should universities or other facilities wish to see the protocol, collaborators may pass it to them as well. Any publications of the protocol will be advertised through social media. The results will be presented at national and international conferences by the principal investigator and supervisor. All presentations will be coordinated by the principal investigator and supervisor to avoid duplications and to ensure all conference regulations are fulfilled. In addition, the results will be disseminated via publication in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

DISCUSSION

There are many factors that could facilitate, but also hinder, a young person from experimenting with roles and going through the normative adolescent crisis (Oleszkowicz, 2006). One of the important factors limiting the “consent to growing up” may be the situation of a family struggling with a chronic disease or disability (Çelik et al., 2018; Iriarte & Ibarrola-Garcia, 2010). A teenager with a disabled sibling is faced with tasks that are unusual for adolescence. Very often, family members directly or indirectly deny him the right to “take care of himself, focus the family’s attention on himself” due to the need to deal with the challenge of raising a disabled child (Laird, 2009). Having a disabled sibling is analyzed in the literature from two main perspectives: threat and opportunity/resource for development.

Children with disabled siblings often receive less attention from their parents and other family members and friends, and consequently feel lonely, unimportant and rejected. Therefore, they often experience a sense of injustice, jealousy and anger towards sick siblings, which may then result in hyperactivity, irritation and aggression manifested in school and peer functioning (Knecht et al., 2015), as well as adaptation problems (Ferraioli & Harris, 2009). Among the siblings of disabled children, there is also a lowered self-esteem and a lack of self-confidence. They are also often referred to as “forgotten people”, whose responsibility is to care for sick siblings (Mikami & Pfiffner, 2008). In addition to mental problems, children with disabled siblings are more likely to experience various somatic complaints (headaches, general feeling of weakness) and problems with sleeping and eating (Knecht et al., 2015). Research also indicates that adolescents in this group exhibit higher levels of depression, separation anxiety, and internalizing behaviors (Lovell & Wetherell, 2016; Lovell & White, 2018).

The resource perspective, in turn, indicates a higher sense of responsibility, self-efficacy and pride in caring for sick siblings (Roper et al., 2014). Less quarrelling and competition among siblings (Kaminsky & Dewey, 2001), an increased level of empathy (Cuskelly & Gunn, 2003), and an increase in self-control (Mandleco et al., 2003), tolerance and understanding (Mulroy et al., 2008) are observed in siblings of children with disabilities.

Summarizing the above, in reference to the extensive body of literature, both favorable and unfavorable factors related to having a disabled sibling can change the development trajectory characteristic for adolescence: they may increase the risk of mental and behavioral disorders typical of adolescence, but they can also shorten the time of adolescence because the teenager has to “grow up quickly”. The proposed project may contribute a theoretical framework of the role of sibling disability as a potential opportunity or threat to development of the adolescent. The project combines research problems specific for several subdisciplines of psychology – family psychology, clinical psychology and developmental psychology – concentrating them around issues of growing up with a disabled sibling. Consequently, this project will focus on both individual and family factors and their role in going through adolescence from the healthy child’s perspective. Furthermore, the functioning of adolescents in three environments – family, peers and school – will be investigated. The above-presented comprehensive approach to the issue of disability in the family from the perspective of a healthy child will allow for a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the process of growing up with disabled siblings.