BACKGROUND

Providing quality mental health care to institutionalised older adults poses a critical challenge, given the rapidly growing ageing population for whom institutional care often becomes a necessity (Chao et al., 2006). In the fourth quarter of life, people experience the most significant increase in negative and decrease in positive emotions (Jasielska, 2011). Older adults are more likely to experience negative emotions (Ferring & Filipp, 1995). In elderly care facilities, they have to cope with emotions such as sadness, pain, fear (Sadavoy, 2007), and guilt, which are more common in older adults than in younger adults (Ready et al., 2011). Social isolation and loneliness are also among the problems of older adults (Luanaigh & Lawlor, 2008; O’Rourke et al., 2018). While loneliness is a subjective experience, social isolation is an objective condition (Barański & Poprawa, 2025). These factors affect 39-72% of older adults (Savikko et al., 2005) and seriously impact those living in care homes (Jansson et al., 2017). They contribute to negative assessments of health and well-being (Golden et al., 2009) and lower quality of life (Trybusińska & Saracen, 2019).

One way to effectively respond to these challenges is to use educational interventions that target educational, cultural and social-psychological goals (Čornaničová, 2000). This study focuses primarily on the social-psychological level of education. Within psychological therapy, Gardiner et al. (2016) highlight the considerable impact of laughter therapy (Tse et al., 2010), reminiscence therapy (Liu et al., 2007) and interventions aimed at improving cognitive abilities and social skills (Saito et al., 2012).

Laughter therapy is an effective non-pharmacological intervention that should be regularly incorporated into the daily care of older adults (Tse et al., 2010). It significantly contributes to increasing quality of life and psychological well-being, promotes well-being and mood, and facilitates the experience of positive emotions (Low et al., 2013; Martin, 2007; Yim, 2016), e.g., happiness (Low et al., 2013; Martin, 2007; Tse et al., 2010) and joy, and the reduction of negative emotions (Martin, 2007; Yim, 2016), e.g., anger, guilt (Martin, 2007), and pain (Tse et al., 2010). It enhances interpersonal interactions (Martin, 2007; Yim, 2016), facilitates social communication (Low et al., 2013; Mallett, 1995), and acts as an “ice-breaker” (Mallett, 1995). It increases the experience of life satisfaction (Tse et al., 2010) while reducing feelings of loneliness (Martin, 2007; Tse et al., 2010).

Reminiscence therapy is an effective non-pharmacological intervention to enhance the mental health of institutionalised older adults (Zhou et al., 2012). It promotes social interaction, improving relationships between staff, residents and families (Latha et al., 2014; Miller, 2009). It contributes to psychological well-being (Cotelli et al., 2012; Moral et al., 2014), improved mood (Cotelli et al., 2012) and life satisfaction (Chou et al., 2008; Moral et al., 2014). It promotes a decrease in the experience of negative emotions (Chou et al., 2008), e.g., pain (Latha et al., 2014), and an increase in the experience of positive emotions (Haight et al., 2006), e.g., happiness (Chin, 2007). It releases energy and emotions, thereby improving mood. Therapy facilitates peer communication, stimulates the development of communication skills (Miller, 2009), and reduces feelings of loneliness (Liu et al., 2007).

Interventions that stimulate cognitive abilities and social skills promote improved psychological well-being (Greene & Burleson, 2003; Mellor et al., 2008; Pitkälä et al., 2011; Saito et al., 2012), enhanced quality of life, positive emotional experience, and happiness (Greene & Burleson, 2003). They contribute to the elimination of social isolation and feelings of loneliness, and encourage higher levels of social activity and the development of social networks (O’Rourke et al., 2018; Saito et al., 2012). They positively affect optimism (Mellor et al., 2008), subjective well-being (Pitkälä et al., 2009) and cognitive health (Pitkälä et al., 2011), and strengthen social bonds (Mellor et al., 2008).

RESEARCH PROBLEM

The research problem of the study is based on the findings of the aforementioned research (e.g., Ferring & Filipp, 1995; Jansson et al., 2017; Jasielska, 2011; Luanaigh & Lawlor, 2008; Ready et al., 2011; Sadavoy, 2007; Savikko et al., 2005), expert recommendations and the observations from a particular facility. Although the physiological needs of older adults are effectively met in a particular elderly care facility, areas of social service recipients’ psychological and social survival remain largely unmet. To date, residents’ participation in the standard activities offered has been limited, with a low activation level and participation of older adults in the facility’s activities.

The Activation-Socialisation Intervention Programme (A-S IP), based on three concepts (Laughter Therapy, Reminiscence Therapy, and Cognitive Abilities and Social Skills Stimulation Intervention) of predominantly social-psychological education, has the potential to reduce the rate of experiencing negative emotions (e.g., Chou et al., 2008; Yim, 2016) and feelings of loneliness (e.g., Liu et al., 2007; Saito et al., 2012; Tse et al., 2010), and to increase the rate of experiencing positive emotions (e.g., Haight et al., 2006; Martin, 2007; Mellor et al., 2008) in older adults.

In addition to the above, we present a pilot study conducted in a specific facility, with plans to be extended to a larger population. The study draws on the recommendations of Findlay (2003), who stressed the importance of pilot projects as cost-effective steps to optimise intervention programmes. These projects allow programmes to be modified before their wider implementation and dissemination to larger research samples.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVE

The study’s main objective is to verify the short-term effectiveness of the original A-S IP for the psychosocial survival of older adults at a specific facility.

First specific aim: To reduce the frequency of negative emotional states through the A-S IP.

Second specific aim: To increase the frequency of positive emotional states through the A-S IP.

Third specific aim: To reduce the frequency of feelings of loneliness through the A-S IP.

Research Question 1 (RQ1): Are there significant differences in the rates of experiencing negative and positive emotional states and loneliness between the experimental and control groups of older adults across the measurements (pretest vs. retest)?

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

RESEARCH DESIGN

The research process was based on the rules of a quantitative applied quasi-experimental design, integrating the principles of the comparative and correlational approaches within a multivariate research analysis framework. It was complemented by qualitative feedback. The implementation of the research was carried out in five main phases:

Identification of the problem’s theoretical background and mapping of facilities, environment, services, interests and needs.

Designing a solution per the facility’s requirements and needs.

Design of the A-S IP and preparation of promotional material (posters, video).

Implementation of the intervention incorporating measurements.

Formative and summative evaluation of the intervention.

The research was conducted from 2019 to 2021. It was affected by complications caused by the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and subsequent anti-pandemic measures, including strict quarantine restrictions at the facility. Following the relevant directives and regulations of the Government of the Slovak Republic, ongoing adjustments to the activities, their content, and the scope of the research population were made.

The research was conducted with strict adherence to ethical principles following the Code of Ethics of the Slovak Psychotherapeutic Society (Slovenská psychoterapeutická spoločnosť, 2013), the Code of Ethics for Psychologists (Slovenská komora psychológov, 2016), and the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2024). An external psychologist and psychiatrist were available for the duration of the research. The study has also been approved by the Ethics Committee of Matej Bel University in Banská Bystrica (Identifier: 162/2025). This study was retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT06866015) after data collection was completed.

RESEARCH SAMPLE

The research sample was formed based on opportunity and purposive sampling, with the respondents being older adults from the Hriňovčan care facility for older adults, located in the Slovak Republic. Inclusion criteria were long-term residence in the facility, age over 62, and willingness and ability to participate (no severe cognitive or physical impairments). There were 49 individuals, while four older adults were excluded from the research for objective reasons (physical and mental health problems, unwillingness to participate). Similar to the total research sample, the allocation of participants to the experimental and control groups was done by purposive sampling combined with opportunity sampling. As shown in Table 1, the experimental group consisted of 33 physically and mentally fit individuals who voluntarily chose to participate in the research. The control group consisted of eight older adults who, due to health problems and by their own decision, chose not to participate in the intervention programme. Consequently, the unequal distribution between the experimental and control groups was due to the voluntary nature of participation, a limited number of eligible participants in the facility, the small size of the facility and ethical considerations preventing the exclusion of motivated individuals. There was no experimental mortality during the course of the study, thus ensuring the continuity of participants in the pretest and retest measurements.

The research population consisted of participants with varying demographic characteristics such as gender, age, marital status, religion, and place of origin. In terms of age, there was heterogeneity in the sample when comparing between groups (p = .007), while homogeneity was maintained within the experimental group (p = .947) as well as in the control group (p = .938). Regarding gender, the research population was homogeneous when compared between groups (p = .695). However, heterogeneity was identified within the experimental group (p < .001) as well as within the control group (p < .001).

Participants provided Informed Consent for the Processing of Social Service Recipients’ Personal Data and Informed Consent to Participate in the Project. The Affidavit of Confidentiality of Information was adhered to during and after the research.

RESEARCH TOOLS

The Scale of Emotional Habituation of Subjective Well-Being (SEHP; Džuka & Dalbert, 2002) was used to examine the short-term effectiveness of the intervention programme. The self-esteem scale maps the frequency of experiencing positive and negative emotions, totalling 10. Negative emotional experiences consist of six emotions: anger, guilt, fear, pain, sadness, and shame. Positive emotional experiences consist of pleasure, physical freshness, joy, and happiness. The participants responded on a six-point scale (6 – almost always; 1 – almost never). The total score of negative emotions is the sum of negative emotions, and the total score of positive emotions is the sum of positive emotions (Džuka et al., 2021). The levels of the mean values of the emotion measures and their comparison with another population were calculated according to the recommendations of the author of the questionnaire (Jozef Džuka, personal communication, 03.12.2024). Cronbach’s α reaches values of α = .65 for negative emotional states in the pretest measurement, α = .71 for negative emotional states in the retest measurement, α = .75 for positive emotional states in the pretest measurement, and α = .79 for positive emotional states in the retest measurement. The values exceed the minimum required reliability (α > .70), except for negative emotional states in the pretest measurement. An additional variable, loneliness, was added to the scale. It was assessed on an identical six-point scale.

Finally, the Reflection Questionnaire (Ďuricová, 2021) was administered. The questionnaire contained six statements mapping the participants’ satisfaction with the intervention programme. The respondents expressed their level of (dis)agreement on a five-point Likert scale (strongly agree – strongly disagree) in repeated participation, usefulness, pleasantness, appropriateness, disinterest, and annoyance. Three incomplete sentences are also included. The participant’s task was to complete the sentences freely. Responses reflect on what they learned/how the activities helped them, what they liked best about the activities, and which of the activities they would eliminate. Questionnaires and data collection were adapted to the abilities of the elderly. To protect the identity of older adults, unique codes were assigned.

The social workers and social rehabilitation instructor gave brief summarising comments as feedback.

DESCRIPTION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTERVENTION PROGRAMME

The proposed A-S IP (Ďuricová, 2025a, 2025b, 2025c) includes 40 activities of three domains focusing mainly on the social-psychological level of education: the Laughter Therapy Concept (13), the Reminiscence Therapy Concept (13), and the Cognitive Abilities and Social Skills Stimulation Intervention Concept (14). Serving as the methodological foundation of the A-S IP, the three concept publications provide practical guidance grounded in theory and offer actionable recommendations for staff working with older adults. They provide comprehensive descriptions of activities, developed based on the pilot implementation of the programme described in this study. Each activity is structured according to a unified format that includes key methodological parameters (such as the title, concept, implementation date, source of inspiration, objective, target group, methods, forms, duration, required materials, activity description, attachments, reflection questions, notes on the course, practical recommendations, and the authors’ implementation experience).

The implementation of the A-S IP activities was designed for a time period of four weeks during weekdays. In the Hriňovčan care facility for older adults, mainly in the common room, two activities were implemented daily during the morning and afternoon hours reserved for this purpose. Morning activities (active) were from 10:00 to 11:00 a.m., and afternoon activities (passive) were from 1:00 to 2:00 p.m. The application of the activities was strictly determined and organised according to a time-thematic schedule that applied rules taking into account the biorhythm, performance and changes of the ageing person; the original mode of the day; the diversity of the programme; the evenness of the number of activities of the concept; the time-thematic context; and the attractiveness of the activities. The participants participated in group activities, and their participation was voluntary. The activities were led by three trained social workers with university degrees and one certified social rehabilitation instructor, all employed at the Hriňovčan care facility. Prior to implementation, they completed a training session with the programme author. Due to quarantine measures, the author could not be directly involved in the implementation process; however, detailed methodological guides were provided. The staff remained in regular contact with the author for consultation to maintain fidelity and address any arising issues.

The aforementioned description of the programme and its implementation is detailed in the three publications accompanying the programme, which provide comprehensive guidelines for implementation as well as detailed descriptions of the intervention activities and overall programme structure.

DATA ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were conducted using JASP 0.18.2 and Microsoft Excel 2014. To analyse the distribution of the study population (heterogeneity/homogeneity) in comparing groups by gender and age, the chi-square test and Student’s t-test for two independent samples were used for evaluation. To assess the distribution of the population (heterogeneity/homogeneity) within the experimental group and within the control group, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used. The reliability (internal consistency) was evaluated based on Cronbach’s alpha (α). The assumptions for the mixed ANOVA, namely normality, homoskedasticity and sphericity, were assessed. Due to the number of levels (2), the assumption of sphericity was not tested. Levene’s test was used to verify the assumption of homoskedasticity. Normality was verified through the Shapiro-Wilk test and by assessing the skewness and kurtosis coefficients. If the condition of normal distribution of the data was not met, the recommendations of Blanca Mena et al. (2017, 2023) and Schmider et al. (2010) were followed, after failed attempts to transform the data (e.g., logarithmic transformation, quadratic transformation, inverse transformation, Box-Cox transformation; Osborne, 2010). These authors provide empirical evidence for the robustness of ANOVA under the assumption of a normal data distribution and thus do not preclude the use of this statistical procedure. In the case of non-compliance with the normality condition (loneliness variable), the results were supported and verified by the Wilcoxon test (for pairwise comparison) and the Mann-Whitney test (for the comparison of two independent groups). Subsequently, within-subjects and between-subjects effects tests were conducted, followed by post-hoc testing. In addition to statistical significance, descriptive statistics of the above method were presented in the form of graphs and descriptive indicators. Effect sizes (ω2; Cohen’s d;rB) were assessed following the recommendations of Goss-Sampson (2024). Differences in each emotion variable in the experimental group were analysed. Due to the unmet condition of a normal data distribution, the Wilcoxon test was applied.

RESULTS

NEGATIVE EMOTIONS

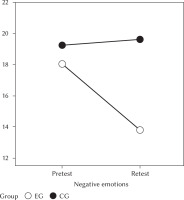

A statistically significant difference was identified between negative emotions across the measurements (pretest vs. retest) (F = 6.88; p = .012), with a small effect size (ω2 = 0.03). The results further indicated a statistically significant interaction between measurement time (pretest vs. retest) and group affiliation (F = 9.81; p = .003), suggesting a small to moderate effect (ω2 = 0.04). Group had a statistically significant effect on negative emotion measures (F = 5.37; p = .026), with the effect size (ω2 = 0.05) indicating a small to medium effect size.

Table 2 indicates a statistically significant difference (pbonf/holm < .001) in the experimental group between the rate of negative emotions before the programme (AMEG = 17.94) and after its completion (AMEG = 13.55). The Cohen’s d value (= 0.99) indicates high substantive significance. Statistically significant differences were noted for most of the individual emotions – sadness (W = 414.50; p < .001), fear (W = 382.00; p < .001), guilt (W = 218.00; p = .002), and anger (W = 202.00; p = .012) – with these differences reaching high substantive significance. The highest correlation value is attributed to the emotion of sadness (rB = .91). In contrast, differences in the values of emotions such as pain (W = 92.00; p = .194) and shame (W = 151.50; p = .075) were not statistically significant.

Analysis of the differences in the control group did not confirm statistically significant changes in the measure of negative emotions (pbonf/holm = 1.000). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the pretest measurement between the experimental and control groups (pbonf/holm = 1.000). On the other hand, in the retest measurement, significant differences were observed between the experimental and control groups (pbonf = .006; pholm = .005), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = –1.36). Figure 1 shows the level of negative emotions before the start of the intervention programme (pretest) and immediately after the intervention programme (retest) in the experimental (EG) and control group of older adults (CG).

Table 2

Post-hoc comparisons – selected interactions of negative emotions, positive emotions and loneliness across the measurements (pretest vs. retest) of the two groups (EG, CG)

POSITIVE EMOTIONS

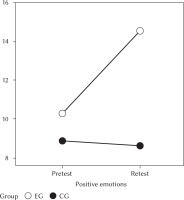

There was a statistically significant difference (F = 23.89; p < .001) with a moderate effect size (ω2 = 0.07) for positive emotions over time (pretest vs. retest). In addition, there was also a significant interaction between the time of measurement (pretest vs. retest) of positive emotions and group type (F = 30.25; p < .001), indicating a medium to strong effect (ω2 = 0.09). Between-group differences in positive emotion rates across measurements (pretest vs. retest) reached statistical significance (F = 13.24; p < .001), with a nearly strong effect (ω2 = 0.13).

As presented in Table 2, a statistically significant difference was observed in the experimental group (pbonf/holm < .001) between the measurements of positive emotions before (AMEG = 10.42) and after (AMEG = 14.12) the intervention. Again, the Cohen’s d value (–1.54) indicates high substantive significance. Most of the specific emotions showed statistically significant differences – enjoyment (W = 32.50; p < .001), physical freshness (W = 31.50; p < .001), joy (W = 19.00; p < .001), and happiness (W = 21.00; p < .001) – with sizeable substantive significance. The emotions happiness (rB = –.92) and joy (rB = –.91) have the highest correlation values.

The results of the difference-in-differences analysis in the control group indicate the absence of statistically significant changes in the level of positive emotions (pbonf = 1.000/pholm = .735). Similarly, there was no significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the pretest measurement (pbonf = 1.000/pholm = .391). On the other hand, in the retest measurement, significant differences were observed between the experimental and control groups (pbonf/holm < .001) with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 2.14). Figure 2 shows the rate of positive emotions experienced before the implementation of the intervention programme (pretest) and immediately after the intervention programme (retest) in the experimental (EG) and the control group (CG).

LONELINESS

A statistically significant difference in loneliness rates over time was identified (pretest vs. retest) (F = 13.67; p < .001), with the effect size reaching a moderate level (ω2 = 0.07). In addition, there was a statistically significant interaction between the loneliness rate across measurements (pretest vs. retest) and group type (F = 18.91; p < .001), with a moderate to strong effect size (ω2 = 0.09). The difference in loneliness rates between groups across measurements (pretest vs. retest) was statistically significant (F = 9.47; p = .004), with a medium to strong effect (ω2 = 0.10).

Table 2 shows statistically significant data in the experimental group (p/pbonf/holm < .001) between pre-intervention (AMEG = 4.12) and post-intervention (AMEG = 2.58) loneliness rates. The Cohen’s d value (= 1.51) indicates a high substantive significance of the difference.

Figure 3

Rates of loneliness over time (pretest vs. retest) in the two groups (EG, CG)

Note. Pretest – pretest measurement; Retest – retest measurement; EG – experimental group; CG – control group.

Analysis of differences in the control group showed no statistically significant differences in loneliness rates between the measurements (p/pbonf/holm = 1.000). There were also no statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups in the pretest measurement (p/pbonf/holm = 1.000; p = .646). In contrast, significant differences between the experimental and control groups were observed in the retest measurement (p/pbonf/holm < .001), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = –1.88). Figure 3 illustrates the extent of experiencing feelings of loneliness before (pretest) and after the intervention (retest) in the experimental (EG) and control group (CG).

DISCUSSION

IMPACT ON NEGATIVE EMOTIONS

The impact of the A-S IP significantly reduced negative emotional states in the older adults who participated in the programme. This supports the assumption that the A-S IP effectively intervenes in negative emotions in general, which is consistent with the results of other studies (Chou et al., 2008; Martin, 2007; Yim, 2016). The programme significantly contributed to the reduction of sadness, fear, guilt, and anger, with the emotions ranked in descending order of their reduction due to the intervention. Martin (2007) also commented on the elimination of anger and guilt.

However, a concerning finding was that pre-intervention participants showed one of the highest values in experiencing pain (in comparison to other emotions) (Mdn = 3), which was consistent with results from another study (Tse et al., 2010). Although Laughter Therapy and Reminiscence Therapy, as components of the A-S IP, are generally considered effective in reducing pain intensity (Latha et al., 2014; Tse et al., 2010), no statistically significant decrease was observed in this study. This result may be influenced by the specific conditions of the participants, who had experienced COVID-19 before the intervention, which could result in a previous occurrence of higher pain survival values. This factor is important for interpreting the results and suggests that the effects of COVID-19 may also explain higher pre-intervention pain levels. The Laughter Therapy and the Reminiscence Therapy were components of a broader intervention package within the A-S IP that included other therapeutic approaches and thus were not applied in isolation.

Although the programme had no significant effect on experiencing shame in this study, the impact of the intervention was still present. This may be because the concepts underlying the programme focus on a general reduction of negative emotions (Chou et al., 2008; Yim, 2016) rather than a targeted intervention on specific emotional states such as shame. Although the programme did lead to a reduction in the experience of shame, its effects were only evident in the broader area of reducing negative emotions.

In the control group, no statistically significant differences were found in the pretest and retest measurements of experiencing negative emotions, suggesting a lack of effect and possible improvement in this area. Although no improvement was found, we observed a slight deterioration in the experience of negative emotions, which may be due to the natural processes of ageing, the absence of intervention or the effects of COVID-19. This result supports the finding that the absence of intervention programmes, such as the A-S IP, may lead to stagnation or worsening of negative emotions among older adults.

IMPACT ON POSITIVE EMOTIONS

The A-S IP had a positive short-term effect on the participants’ experiences of positive emotions. The programme significantly increased the frequency of experiencing emotions such as enjoyment, physical freshness, joy, and happiness, with the most significant impact being the increase in experiencing joy and happiness. An increase in happiness was also reported by Chin (2007), Greene and Burleson (2003), Low et al. (2013), Martin (2007), and Tse et al. (2010). These findings are consistent with other literature (Cotelli et al., 2012; Greene & Burleson, 2003; Haight et al., 2006; Low et al., 2013; Martin, 2007; Mellor et al., 2008; Miller, 2009; Moral et al., 2014; Pitkälä et al., 2011; Saito et al., 2012; Yim, 2016), which also shows the positive influence of intervention programmes on experiencing positive emotions in older adults in general.

Before the programme, the participants experienced low levels of positive emotions (AM = 10.42), which is consistent with the findings of a study (Jasielska, 2011) that reported lower intensity and frequency of positive emotions in old age.

The control group did not improve in experiencing positive emotions, which again supports the fact that the control group, without intervention, showed no statistically significant improvements. The above suggests that positive emotions in that group remained unchanged, contrasting with the significant improvements in the experimental group. The result illustrates the potential of using intervention programmes, such as the A-S IP, to increase the intensity of positive emotions.

IMPACT ON LONELINESS

In the short term, the A-S IP had a positive effect on reducing the experience of feelings of loneliness in the older adults who participated. The results of this study show that the reduction in the intensity of loneliness was consistent with the results of other research (Liu et al., 2007; Martin, 2007; O’Rourke et al., 2018; Saito et al., 2012; Tse et al., 2010), confirming that socialisation and activation interventions can significantly contribute to improving older adults’ social well-being and reducing feelings of loneliness.

Before the intervention, high levels of loneliness (Mdn = 4) were observed in the experimental group, which is in line with the findings of other authors (Jansson et al., 2017; Savikko et al., 2005), highlighting the high rates of loneliness and their consequences among older adults in care settings. Given this, it is important to highlight that in elderly care facilities, where loneliness is a significant problem (Luanaigh & Lawlor, 2008) with serious consequences (Jansson et al., 2017), such feelings may be exacerbated by external factors such as quarantine measures. Findings suggest that quarantine measures that limited social interactions between older adults and their families may have had a negative impact on levels of loneliness, causing higher pre-intervention levels of loneliness than would have been the case under normal conditions.

The control group’s experience of loneliness remained unchanged, confirming that the absence of the intervention did not lead to an improvement in this area. In contrast, there was a statistically significant decrease in feelings of loneliness in the experimental group, demonstrating the effectiveness of the A-S IP in reducing loneliness among older adults. In the control group, high values of loneliness were observed pre-intervention, with no significant improvement noted post-intervention. This may be due to socio-environmental factors or the absence of targeted activities.

RESEARCH LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE FUTURE

Research sample size and selection:

a) Small sample size and limitations in statistical analysis. The control group was small, which limits the generalisability of the results and reduces the reliability of the statistical analyses (Button et al., 2013). Similar to Chao et al. (2006), Chin (2007) and Gardiner et al. (2016), it is recommended that further empirical studies be conducted with larger samples and thus more representative results.

b) Heterogeneous characteristics and limited comparability of experimental and control groups. Demographic characteristics such as gender and age were recorded and tested for homogeneity; however, heterogeneity was found between the groups in terms of age and within the groups in terms of gender. Other relevant variables, such as the level of psychiatric disorders, marital status, religion, and place of origin, were also not considered. Moreover, the groups had an uneven number of participants due to the reasons outlined above. These factors may have affected group comparability and, consequently, the external validity and interpretation of differential effects (Chao et al., 2006; Chin, 2007; Cotelli et al., 2012). Stratified selection with balanced variables and the use of advanced statistical methods is recommended to reduce group differences and control for confounding factors.

c) Potential bias in the research sample. The voluntary participation of older adults may lead to selection bias because participants tend to be healthier or more motivated. This may affect the interpretation of the results and reduce the internal validity of the study. Randomised selection of participants or clear communication of uncertainty in the interpretation of results is recommended (Greenland, 2005).

d) Sample selection from a single facility. A quasi-experiment conducted in a single facility may suffer from lower ecological validity due to the specificity of the setting and a combination of purposive and opportunistic sampling. This limits the generalisability of results to other facilities or populations. It is advisable to replicate the study in different facilities and regions with a diverse range of participants (Findlay, 2003) to increase the ecological validity and applicability of the results, contributing to higher variability and more robust findings (Bickman, 1990).

Limited measurement reliability. The low reliability of some variables, especially negative emotional states in the pretest measurement, may have affected the significance of the results. Replication of the study is recommended to improve the reliability of the findings.

Absence of follow-up assessment. Another limitation is the absence of a measurement to analyse the long-term effectiveness of the activities or the sustainability of their effects. Due to the original intention of the pilot study, organizational constraints, and adverse circumstances related to quarantine measures during the pandemic, the follow-up measurement was not conducted. Additionally, the inability to access the original sample after the pandemic, potential bias in results caused by the pandemic, and the effort to avoid placing an additional burden on participants during this challenging period contributed to this decision. Although the intervention activities have continued to be implemented in practice in a limited form, their long-term impact was not empirically monitored. A follow-up measurement after a defined interval is recommended to assess the sustainability and long-term effectiveness of the interventions (Chao et al., 2006; Findlay, 2003). Integrating elements of the intervention programme into daily routines is essential, as one-off activities may provide short-term benefits but rarely result in lasting improvements without consistent application.

Impact of uncontrolled external factors. A quasi-experiment is influenced by many external factors, such as physical, social, economic, and political circumstances that are not under the researcher’s control (e.g., COVID-19, relationships, financial income, or health care). Due to pandemic-related restrictions, direct involvement of the researchers in the implementation of the intervention was not possible. It is recommended to clarify and control such factors, replicate the study, use multiple control groups, and apply advanced statistical analyses, such as linear random-effects models.

CONTRIBUTION OF THE RESEARCH AND ITS PRACTICAL APPLICABILITY

The research offers a novel perspective on combining therapeutic approaches in working with older adults. It also provides a practical implementation methodology for staff which, in the given context, can serve as a foundation for larger studies and practical integration into the daily routines in elderly care facilities. This may contribute to both the short- and long-term improvements in their quality of life.

This approach has demonstrated meaningful impacts in the short term, especially at the social-psychological level of education of older adults and at the educational and cultural levels. The participation of older adults in activities has increased significantly. Older adults have seen improvements in various areas of their lives. Most of them reported that the activities enhanced their ability to work with their roommates and deepened their respect for each other. Togetherness among them was strengthened, and communication became more effective. Their confidence in speaking in front of others increased, leading to formation of new social bonds. Participants often reported that they forgot about everyday problems during the activities and found joy in little things. They gained a broader view of what was happening in the facility, the region, and the community and a better understanding of the individual experiences of other members. In addition, they experienced positive changes in memory, attention and ability to concentrate. This suggests not only personal benefits but also a positive change in quality of life and the facility’s overall atmosphere.

The older adults identified the most successful activities as Vtipné zadanie [Funny Task], Mačka vo vreci zábavnou formou [Cat in the Bag – Fun Version], Remeslá [Crafts], Aká bola moja svadba? [What Was My Wedding Like?], the quiz Môj súčasný domov [My Current Home] and Ružové okuliare [Rose-Tinted Glasses]. They highlighted the joyful and fun atmosphere that evoked laughter, the stimulation of memories bringing back positive emotions and long-forgotten past events, and the competitive element with rewards as the programme’s best features. Participants emphasized that they would not remove any part of the programme.

The preceding data are corroborated by the following findings, which provide feedback on the implementation of the A-S IP. The results, expressed as relative frequencies (summing the “strongly agree” and “agree” categories) are as follows:

91% of participants would participate in a similar programme again.

94% rated the programme as useful.

91% rated it as enjoyable.

88% rated it as appropriate.

85% disagreed with the statement that the programme was uninteresting.

88% disagreed with the statement that the programme was bothersome.

The activities received positive feedback not only from the older adults but also from social workers, the social rehabilitation instructor, other professional staff, and the facility director. They requested that the original methodological guides developed for the programme, along with the related materials, be left in the facility. Their request was fulfilled, and the activities continue to be implemented with respect to the recommended guidelines.

Finally, the social worker’s comment on the developed programme is presented: “Do you want to break the boring stereotype and activate seniors with innovative strategies? Then this programme is optimal for you! Original activities, diverse material, a friendly approach, ... Memories and funny situations got me too! Excellent! The ladies were delighted, and the men were too! Looking forward to further cooperation!”

CONCLUSIONS

The A-S IP has proven its effectiveness in the short term. Results from the experimental group indicate a significant reduction of negative emotional states and an increase in positive emotional states, with the programme having the most pronounced impact on emotions such as happiness, joy, and sadness. In addition, there was a reduction of feelings of loneliness after the intervention. These quantitative results were supported by qualitative feedback from the participants and the institution’s staff. Participants evaluated the programme positively and noted improvements in the social-psychological dimension of education and the educational and cultural dimension. Many participants stated that they would participate in a similar programme again. They agreed with the statements that the programme was helpful, enjoyable and appropriate.