BACKGROUND

The modern world imposes on people the necessity to cope with a multitude of demanding and stressful situations. It seems crucial nowadays to take actions supporting life and job satisfaction since it has an impact on functioning in some areas; for example, psychological well-being is related to performance ratings (cf. Wright & Cropanzano, 2000). It is therefore essential to strengthen internal employee resources such as a growth mindset and self-efficacy (Dweck, 2017; Judge et al., 2005).

As demonstrated by numerous studies carried out by Dweck (2017), a growth mindset supports individuals in coping with difficult and challenging situations. It constitutes a driver for pursuing actions related to acquiring new competencies that assist in the fulfillment of tasks (Dweck, 2017). The research also demonstrates that the higher the growth mindset of anxiety is, the lower is the severity of psychological distress, and the less frequent is the experience of stressful life events (Schroder et al., 2017). A growth mindset can represent a protective resource against the adverse effects of stress caused by the demands of the modern world that reduce life and job satisfaction. According to earlier studies, self-efficacy is also one of the internal resources which enable individuals to cope with difficult situations (Benight & Bandura, 2004). It also influences thoughts, i.e., whether we are optimistic or pessimistic (Bandura, 2001). Furthermore, it supports individuals in dealing with stress at work (Maggiori et al., 2016).

Present-day stress is associated with the pandemic, which has had a downward effect on job satisfaction and satisfaction with family life (Möhring et al., 2021). Research shows that we are observing major consequences of this situation for health and social functioning, including a deterioration of subjective well-being (Kowal et al., 2020; Trougakos et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020), as well as an increase in perceived stress (Grover et al., 2020) and increased anxiety and depression (Twenge et al., 2021). The global pandemic has taken a toll not only on our well-being (Twenge et al., 2021) but also on employee relations and the employee–organization relationship due to the need to transform how we work (cf. Finset et al., 2020). It is therefore justified to seek resources that allow individuals to increase satisfaction with various areas of life.

As we know that a growth mindset strengthens satisfaction, it is worth evaluating whether stress and self-efficacy can mediate the relation between these variables.

GROWTH MINDSET AND LIFE AND JOB SATISFACTION

Dweck (2017) emphasizes that people differ in their attitude towards challenges, successes, and failures. Those with a growth mindset feel satisfied with their actions and are convinced that their success depends on the effort expended (Yeager & Dweck, 2012). People with a fixed mindset are convinced that their character traits influence the achieved results, and therefore they feel no need to work on their development, which means that in the face of failures, they lose interest in further activities and limit their work to a minimum. They avoid tackling challenges due to a fear of undermining their competencies (Ehrlinger et al., 2016). They see the achieved result as the most important and as proof of their perfection and superiority (Burnette et al., 2013). On the other hand, the motive of development-oriented people is the desire to exceed their capabilities and search for new, more effective strategies (Dweck, 2017). Such individuals feel motivated to take action to improve a certain situation (Van Tongeren & Burnette, 2018). These people assess their competencies and efforts more accurately, and when they make a mistake, they try to correct it; in no way does it undermine their self-confidence (Dweck, 2017). They use mastery-oriented strategies instead of helpless-oriented strategies (Burnette et al., 2013). There is no place here for negative emotions resulting from a fear of failure or competition (Dweck, 2017). On the other hand, optimistic expectations evaluations can be seen (Burnette et al., 2013). Stress perceived by challenge-oriented people allows them to perform work more effectively by enhancing positive affect and cognitive flexibility (Crum et al., 2017). Owing to these relationships, a growth mindset is considered as an individual resource. It is strongly correlated with creative self-efficacy and creative personal identity and solving insight problems (Karwowski, 2014). It influences self-regulatory processes and outcomes (Molden & Dweck, 2006). Research shows that it has a beneficial effect on various areas of life; e.g., there is a clear positive relationship between a growth mindset and well-being. Looking further ahead, a growth mindset is associated with higher job satisfaction and health (Van Tongeren & Burnette, 2018). It also influences the perception of a situation as more positive, even when, as an employee, the individual has experienced negative behaviors from colleagues (Rattan & Dweck, 2018). This arises because he or she believes in the ability to change the others’ behavior. The growth mindset reinforces the sense of belonging to the organization and the assessment of relations with colleagues and translates into job satisfaction. Students subjected to growth mindset interventions exhibit higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy and persistence, which indirectly contributes to the growth of interest in science and a career in a selected area (Burnette et al., 2020).

SELF-EFFICACY AND LIFE AND JOB SATISFACTION

The social cognitive theory emphasizes the interaction of the person and the environment, as well as the variability of behavior, which is a response to environmental shifts (Bandura, 1977). Its key element is the perception of self-efficacy as a cognitive process that mediates action (Bandura, 1977). Self-efficacy significantly affects thoughts, which can encourage or discourage an individual from acting (self-enhancing or self-debilitating way of thinking), including in the face of difficulties or stress: “belief in one’s capability to exercise some measure of control in the face of taxing stressors promotes resilience to them” (Benight & Bandura, 2004, p. 1131). In the context of work, this seems to be of particular importance because the level of self-efficacy affects how people function. Those with a high level of self-efficacy choose to perform challenging tasks; they are more persistent and put more effort into their implementation, compared to people with a low level of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). Moreover, self-efficacy supports the employee in coping with stressors at work (Perrewe et al., 2002), and the level of perceived stress is negatively related to that of self-efficacy (Rayle et al., 2005). Self-efficacy also represents a key mediator in recovery and helps the individual cope with the effects of stress (Benight & Bandura, 2004).

Traumatic experiences such as natural disasters or catastrophes are difficult for humans and adversely affect psychological well-being. Self-efficacy plays a key role in the quality of coping with a threatening situation, as well as the stress that arises at that time (Bandura, 1997). Self-efficacy means the way in which the individual perceives his ability to cope with various demanding situations, e.g., recovering from various traumatic experiences (Bandura, 1997; Benight & Bandura, 2004). And so, although an individual experiences negative emotions in a threatening situation, he feels in control of the situation (Bandura, 1997). As demonstrated by international studies, high self-efficacy allows an individual to maintain a high level of optimism, life satisfaction, and positive affect, and reduce anxiety and depression (Luszczynska et al., 2005). Self-efficacy also mediates the relationship between the feeling of job insecurity and the acquisition of new skills, competencies or knowledge by an employee (Van Hootegem et al., 2022). It represents a predictor of life satisfaction (Bandura, 1997; Luszczynska et al., 2005) and job satisfaction (Judge et al., 2000; Luszczynska et al., 2005; Mishra et al., 2016; Nair & Dovina, 2015). The self-efficacy level may explain how the professional, family and social requirements related to a difficult situation influence the employee’s functioning in the new reality and his satisfaction with various areas of life.

STRESS AND LIFE AND JOB SATISFACTION

Stress is defined variously depending on the discipline of science in which it is described (Le Blanc et al., 2003). It can be perceived as a stimulus, as a reaction, and as a process between the stimulus and the reaction. Stress, as a disruption of human functioning in a specific environment, is the result of specific relationships between internal and external factors (Heszen-Niejodek, 2000), i.e., the person and the environment (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Psychology highlights that it depends on a subjective assessment of the situation (cf. Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), as well as on the cultural and social context (cf. Hobfoll, 2006). In his concept, Hobfoll (2006) notes that stress occurs when an individual’s resources are at risk of being lost or are in fact being lost, and when there is a failure to recover resources. Resources are essential to deal with a stressful situation (Hobfoll, 2006). The more resources we possess, the less likely we are to lose them. The fewer resources we own, the more we are afraid of losing them, and we can invest them in the process of coping with a difficult situation to a lesser extent. Personal and situational resources mediate between job demands and the stress response (Le Blanc et al., 2003).

Employees experience stress in situations of a conflict between their skills and the requirements of the environment or when their competences are not consistent with the resources present in the work environment (Le Blanc et al., 2003). Research indicates that stress at work reduces job satisfaction and translates into turnover intentions (Kim et al., 2015; Orgambídez & Extremera, 2020). The relationship between stress and life satisfaction is mediated by a positive attitude, approach coping style and mature defense mechanisms (Gori et al., 2020). Stress at work resulting from the instability and insecurity of employment reduces the satisfaction with the superior’s support and the possibility of promotion (Nemteanu et al., 2021). Job instability, on the other hand, further reduces overall job satisfaction. And as is common knowledge, experienced stress reduces life satisfaction and happiness (e.g., Hamarat et al., 2001; Schiffrin & Nelson, 2010). It is therefore important to identify resources that will allow the individual to maintain the level of life and job satisfaction, regardless of the effects of experiencing a difficult situation.

RESEARCH AIM

Having regard to the literature, it can be assumed that the growth mindset has a significant impact on life and job satisfaction (cf. Godlewska-Werner et al., 2021; Van Tongeren & Burnette, 2018; Zeng et al., 2016). On the other hand, a mediating role in this relationship may be played by stress, which reduces the level of satisfaction (cf. Nemteanu et al., 2021; Orgambídez & Extremera, 2020), as well as self-efficacy, which has a positive effect on life and job satisfaction (cf. Bandura, 1997; Judge et al., 2000; Luszczynska et al., 2005). The present article centers around the role of the growth mindset as an internal resource helping an employee cope with stress and increasing life and job satisfaction, as well as an intermediary role of self-efficacy between the growth mindset and life and job satisfaction.

Therefore, taking account the above-described reports, the following hypotheses were put forward in the present study:

H1: A growth mindset increases life and job satisfaction, but experiencing a high level of stress weakens this relationship.

H2: A growth mindset increases life and job satisfaction also through the prism of a sense of self-efficacy.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The hypothesis was verified by performing research on a group of 283 employees (aged M = 30.86, SD = 11.33). Women were the most numerous group, i.e., 69% of the sample, and there were 88 men, which represented 31%. All respondents had a tertiary degree. The majority of the respondents were employed under an employment contract or self-employed (191 – approx. 68%), while the remaining portion thereof worked under a civil law contract (77 – approx. 27%) or a contract (15 – approx. 5%).

PROCEDURE

The study was carried out during a complete lockdown in Poland in March-April 2020. During that time, there was a significant increase in the number of cases of COVID-19 (WHO, 2020). The survey was conducted anonymously and on a voluntary basis. The study was conducted using the online version of MS Office. The link to the questionnaire was made available to professionally active individuals.

MEASURES

Growth Mindset Questionnaire. The growth mindset was measured using the original version of the Growth Mindset Questionnaire (Godlewska-Werner et al., 2021), which was based on Dweck’s concept of mastery orientation (Dweck, 2017). The questionnaire consists of 14 statements assessed by the respondents on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The sentences relate to the individual’s reaction to failure, approach to difficult tasks, and seeking feedback. In order to check the fit of the model to the data, an analysis was carried out on a sample of 283 people. The one factor model was the best fit for the data (CMIN/DF = 308.62 (77), RMSEA = .010 (LO = .091, HI = .115), p < .001, CFI = .723, GFI = .840).

Life and Job Satisfaction Questionnaire. The study also employed an original questionnaire to measure satisfaction with personal and professional life (Kondratowicz et al., 2022). The basis for the design of the tool is the results of exploratory factor analysis carried out with the SPSS 26 package, based on which three factors were distinguished: satisfaction with personal life (e.g., relationship with partner/spouse, personal/family life, health condition), job satisfaction (e.g., relationships with supervisor and colleagues) and satisfaction with employment conditions (e.g., salary level and opportunities for personal development, employment stability). The distinguishing factors together explain over 40% of the total variance. This tool includes a set of 12 items. The respondents answered on a scale of 0 (dissatisfied) to 10 (satisfied), following the assumptions of Cantril’s Ladder (1965).

Self-efficacy items. Self-efficacy was measured using a 2-item measure of self-efficacy developed by Atroszko et al. (2017) (“Usually, I am able to cope with what happens to me” and “I can solve most problems if I put enough effort into it”). The respondents assessed the extent to which a given statement was true on a scale from 1 (no) to 9 (yes).

Perceived Stress Scale. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4; Cohen et al., 1983) in the Polish adaptation by Atroszko (2015) was used to measure the perceived stress. The questionnaire consists of four questions about recent thoughts and feelings. The respondents report their occurrence on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

RESULTS

The means, standard deviations and reliabilities for all the tested variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Means, standard deviations and reliabilities for tested variables

| Variables | M | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth mindset | 49.93 | 7.37 | .79 |

| Self-efficacy | 13.49 | 2.27 | .82 |

| Stress | 11.22 | 2.89 | .74 |

| Job satisfaction | 7.34 | 1.97 | .89 |

| Satisfaction with employment conditions | 6.04 | 2.28 | .81 |

| Life satisfaction | 6.99 | 1.71 | .73 |

In the first step of the analyses, Person’s r correlation analysis was performed (see Table 2).

Table 2

Correlations between all tested variables

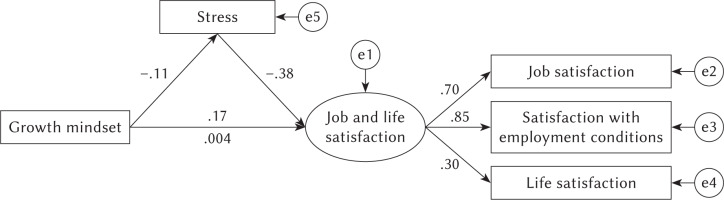

Hypothesis H1 was verified using a mediation analysis with direct and indirect effects of the SEM model using the Amos 26 statistical package. The assumption was that the respondents’ growth mindset increases life and job satisfaction, but through the prism of the intensity of the perceived stress, a high level of which weakens this relationship (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Resulting path diagram of the model of stress as a mediator between growth mindset and aspects of the job and life satisfaction

The results indicated an interpretable fit of the model to the data (Table 3). The model parameters turned out to be acceptable (Konarski, 2010).

Table 3

Goodness of fit indices for the assumed system of variables: growth mindset – stress – subjective well-being

| CMIN = 13.89 (4) | RMSEA = .094 | GFI = .981 | CFI = .949 |

|---|---|---|---|

| p = .008 | p = .073 |

It was found that the respondents’ attitude to growth was statistically significantly positively associated with life and job satisfaction (direct effect: β = .17, p = .052) (Table 4). People who are focused on growth assess aspects of their life and job better. Nonetheless, this relation substantially weakens when assessed through the prism of perceived stress (especially its intensity); however, it remains statistically significant (indirect effect: β = .04, p = .054). In the case of the tested model, there are therefore grounds for talking about the so-called partial mediation on the part of the stress variable for the analyzed variable relation.

Table 4

Stress mediation parameters in the relation of the independent and dependent variable in the assumed model

| Hypothesis | Direct effect | Indirect effect | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth mindset → Stress → Subjective well-being | .17** | .04** | Partial mediation |

Thus, the obtained results provided a basis for confirming the postulated hypothesis H1.

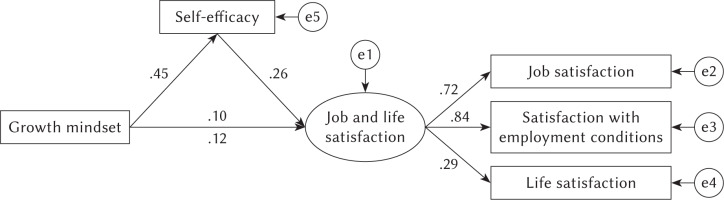

The next step involved analyses performed to verify hypothesis H2 assuming that the growth mindset increases the level of life and job satisfaction also through the prism of the sense of self-efficacy (Figure 2). Again, an analysis of direct and indirect effects was carried out in the SEM model using the Amos 26 statistical package.

Figure 2

Resulting path diagram of the model of self-efficacy as a mediator between growth mindset and aspects of the job and life satisfaction

The results demonstrated that the parameters for fitting the model to the data reached acceptable and interpretable values (Table 5) (Konarski, 2010).

Table 5

Goodness of fit indices for the assumed system of variables: growth mindset – self-efficacy – subjective well-being

| CMIN = 6.68 (4) | RMSEA = .049 | GFI = .991 | CFI = .988 |

|---|---|---|---|

| p = .154 | p = .043 |

Detailed analysis of the data showed that although growth mindset among the respondents is not directly statistically significantly related to life and job satisfaction (direct effect: β = .09, p = .270), taking into account the level of the sense of self-efficacy as an intermediary variable (indirect effect: β = .12, p = .001), this relationship becomes statistically significant (Table 6). This means that the growth mindset only with the sense of self-efficacy helps to increase life and job satisfaction, which in the case of the verified model forms the grounds for concluding the so-called suppression in the relationship between the described variables on the part of the variable “self-efficacy”. Thus, the results indicate that the postulated hypothesis (H2) was confirmed partially.

DISCUSSION

The core aim of this research was to determine the significance of selected internal employee resources such as growth mindset for life and job satisfaction in a situation of increased stress. The study was also aimed at establishing the strength of the relationship between a growth mindset and work and life satisfaction when experiencing increased levels of stress and having a sense of self-efficacy. So far we could note that there is a correlation between a growth mindset, stress and self-efficacy. These variables have been considered separately, so our mediation study extends our knowledge of these interactions.

The first hypothesis assumed that the growth mindset increases the level of life and job satisfaction; however, feeling a high level of stress significantly weakens this relationship. This hypothesis was confirmed. The results agree with the outcomes of previous studies, indicating the protective significance of the internal resources of an individual (Schroder et al., 2017) such as a growth mindset (Dweck, 2017). A growth mindset has a positive effect on the functioning of the individual (Dweck, 2017). In line with the expectations, the study confirmed that a growth mindset was positively associated with life and job satisfaction. This means that development-oriented people, thanks to their readiness to take effective actions, are not afraid of difficult situations. They are convinced that any problem situation can be changed if an adequate effort is made (Yeager & Dweck, 2012) and persistence is shown (Burnette et al., 2020). They tend to perceive difficult situations not as negative but as challenging (Dweck, 2017). Since they do not feel threatened, it does not reduce their satisfaction in various areas of life. Our own research has demonstrated that stress, as predicted, weakens the relationship between the growth mindset and life and job satisfaction, but the relationship remains important. This may confirm the significance of the development focus resource in the context of Hobfoll’s (2006) concept. This concept assumes that the more resources we have, the more we can invest in coping with difficult situations without fear of losing these resources completely. Following the same reasoning, possessing or developing a growth mindset will support satisfaction even in the face of unfavorable and stressful circumstances. The study was carried out in the initial phase of the pandemic, upon the introduction of numerous restrictions (including lockdown and others), as well as changes in everyday and professional functioning, which undoubtedly could have contributed to the experience of high levels of stress by individuals (Grover et al., 2020) and to worsening subjective well-being (Kowal et al., 2020; Trougakos et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). It can therefore be concluded that when experiencing elevated levels of stress, a growth mindset can help workers maintain life and job satisfaction. A growth mindset can lead to satisfaction because of a belief that improvement takes time and needs hard work. That is why a mastery-oriented person does not expect results rapidly and focuses on building abilities even when a situation is not favorable. Lower satisfaction is understandable in a stressful situation, but stress does not reduce satisfaction completely in people who are determined and learn from potential failure.

The second hypothesis was partially confirmed. It seems that a growth mindset only increases the level of life and job satisfaction with a sense of self-efficacy. It means that explaining satisfaction makes more sense when we use two components instead of just one, a growth mindset. The result may suggest that the employee must have a greater number of internal resources, i.e., both a growth mindset and a sense of self-efficacy, to maintain life and job satisfaction. This may demonstrate that to be satisfied with various areas of life, both a belief in the possibilities of actions aimed at the chosen goal and the willingness to exceed one’s capabilities are important. Self-efficacy supports the individual due to a self-enhancing way of thinking (Benight & Bandura, 2004). Owing to this resource, the individual has a stronger feeling that he or she is in control of difficult situations (Bandura, 1997) and has a higher level of optimism (Luszczynska et al., 2005). A growth mindset gives the feeling that the situation in which the individual finds himself can be changed by him and therefore treats it as a challenge and a test of his competencies (Dweck, 2017). Self-efficacy supports the individual in adapting to the situation and enables a proper assessment of it (Bandura, 2001), while the growth mindset allows one to draw conclusions from failures and motivates a person to develop competencies (Dweck, 2017). Previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between development mindset and creative self-efficacy, and solving insight problems (Karwowski, 2014). People who participated in activities fostering a growth mindset exhibited an increased level of self-efficacy, which enhanced their interest in further development (Burnette et al., 2020). On the other hand, individuals with both a high level of growth mindset and a sense of self-efficacy put more effort into the implementation of tasks, compared to people with low levels of these resources (Bandura, 1997; Dweck, 2017), which may suggest that the willingness to take action affects the sense of satisfaction.

LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The study had certain limitations. One of these limitations is that it was carried out online. Therefore, it can be assumed that we managed to reach a specific group of respondents who are more involved in online life. Apart from what has been mentioned, this method of conducting research does not allow for the identification and control of distractors that may have occurred while the respondents were completing the questionnaire. Moreover, the study took into account the general sense of stress. A subsequent study should consider the causes and areas of stress to determine which of the experienced stressors play the greatest mediating role in the analyzed relationship. Since the study was conducted during a pandemic, it can be assumed that the perceived stress is related to this situation to some extent. However, it could result from various fears and concerns, for example, about maintaining employment, coping with changed working conditions, or health. Moreover, demographic variables such as the type of employment or type of position, which were not included due to the structure of the study group, would have to be taken into account. The present study was cross-sectional and the results can be mainly applied to women with an employment contract. That is why it would be useful to verify the differences between men and women as regards perceived stress. As demonstrated by the current research results, the level of perceived stress during the COVID-19 pandemic varies according to gender (e.g., Kowal et al., 2020). It would also be worth extending the sample in the future.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The study enhances knowledge about the role that the employee’s internal resources, growth mindset and self-efficacy play in a situation of increased stress. A growth mindset has been shown to reduce the effects of experienced stress and promote growth in life and job satisfaction. The results constitute a valuable source of information for both employees and employers, guiding what internal resources should be strengthened by employees. There is a plethora of different training courses aimed at developing master-oriented strategies that could be offered to employees. This is crucial as supporting employee satisfaction can translate into their efficiency, engagement, and commitment to the organization (cf. Koys, 2001).

CONCLUSIONS

A growth mindset and self-efficacy help the individual to maintain satisfaction with their job and life during a stressful situation. On the other hand, a growth mindset represents an internal resource that protects the employee from experiencing the negative effects of perceived high levels of stress, supporting his overall satisfaction. It is worth supporting both of these resources among employees because according to Hobfoll’s (2006) approach, the bigger the resource pool possessed by the individual, the lower is his susceptibility to stress. Beside that, both of these beliefs positively affect life and job satisfaction, which is important for effective functioning in various areas of life (cf. Bandura, 1997; Dweck, 2017).