BACKGROUND

Numerous revolutionary changes in the social, technological and economic environment in recent years have contributed to the emergence of new paradigms in managing people and organizations. On one hand, digitalization and automation have changed the nature of work and the competencies required of employees, which affects organizational cultures and climates. On the other, the growing popularity of flexible work arrangements and the appreciation of employee well-being and mental health are becoming increasingly vital for organizational effectiveness. The paradigm is shifting from a transactional to a relational, human-centered approach, where the employee is not merely a resource but an integral component of a dynamic organizational ecosystem – a carrier of competences, values, expectations, needs (social, emotional, spiritual) and agency.

With that shift, the concepts of employee experience (EX) and well-being (EWB) gain in popularity and trigger increased interest among both researchers and human resources practitioners. According to Das and Dhan (2023) publications on the topic of employee experience have seen exponential growth over the past few years; well-being is even more explored in the scientific literature as the key topic of concern for the International Labor Organization (Samans, 2024) or the World Health Organization, as highlighted in the evidence-based guidelines for mental health at work published in 2022 (WHO, 2022).

Both these concepts are complex and broad, and the boundaries between them seem blurred, which might impede the processes of management and implementation of activities aligned to them. This, in turn, may explain why numerous well-being or EX initiatives do not work, as highlighted in recent publications (Daniels et al., 2022; Fleming, 2024; Song & Baicker, 2019).

Therefore, there is a huge need to better understand the interconnectedness of employee experience and well-being as well as the extent to which organizations incorporate the growing knowledge base into their human resource management (HRM) practices.

Considering the theoretical uncertainty and scarce evidence from practice, the main objective of this paper is to review and compare the dominant theories defining EWB and EX, their antecedents and effects within an organizational environment and the relations between these two phenomena in the scientific literature and practitioner papers. The article’s empirical part focuses on practical considerations and difficulties in bringing the two components together in creating a healthy work environment and increasing workers’ satisfaction and performance. Based on the aforementioned goals, we posed four research questions:

To what extent does the overall employee experience theoretical framework align with employee well-being theory? What are the similarities and differences?

How are the two issues understood by practitioners and implemented in companies?

Who is usually responsible for implementing the ideas of EX and EWB? Are these the same persons/departments?

What types of initiatives are delivered in terms of EX and EWB? What is the main focus within them?

Theoretical analyses help to answer the first research question, and quantitative survey research on HR professionals illuminates the understanding and practical implications of the two phenomena. Practical concerns and limitations of the study are outlined in the discussion part of this paper.

WELL-BEING AND EMPLOYEE WELL-BEING

The most general term that defines well-being refers to how individuals evaluate their lives, including mental state, social life, health, work environment, and material issues (Diener, 1984; Searle, 2008; Seligman, 2018). Two main concepts of well-being have been presented in the literature: hedonistic and eudaimonic well-being. Hedonistic well-being, which results from the feeling of pleasure and the absence of pain (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryff & Keyes, 1995), is disturbed in each situation when a person suffers from sadness and abandonment or general pain due to deprivation of needs. On the other hand, eudaimonic well-being is described as a sense of meaning and self-worth (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Job insecurity, prolonged unfitness to work and inability to meet job demands are the reasons for this type of well-being declining.

Seligman’s concept of well-being (PERMA) focuses on five “building blocks” that allow a person to flourish: positive emotions (about past, present and future), engagement (full deployment of one’s skills and attention for a task), relationships (based on positive feelings of joy, pride, belonging and accomplishment), meaning (derived from belonging to and serving noble aims) and accomplishment (pursuing achievement, success and mastery) (Seligman, 2018). According to the author, a high level of well-being benefits high performance and satisfaction as well as better physical and mental health.

It is also worth noting that World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realises their own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to the community” (WHO, 2018).

Well-being can be considered from an organizational or private perspective, and the issue of well-being at work is widely described in the literature (Danna & Griffin, 1999; Schulte & Vainio, 2010). Well-being at work or employee well-being (EWB) is a state in which a person feels comfortable, healthy and satisfied. It is associated with activities in all areas of life, including professional activity, as the sense of well-being in the workplace is crucial for general well-being. Well-being at work is sometimes equated with job satisfaction; however, researchers point out its three dimensions (Grant et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2018):

psychological – subjective mental well-being (including job satisfaction, self-esteem, agency and capabilities);

physical – an experience of body health (including physical safety and ergonomics of work, health care);

social – the quality of relationships with other people (including trust, social support, cooperation).

EWB can also be defined as an employee’s understanding of their own capabilities, essential needs, and coping with stress at work. It provides one with a feeling of productive work, contribution to the community, and a sense of security and meaningful work (Van De Voorde et al., 2012). The very concept of well-being is a comprehensive, holistic approach to a human and satisfying their sense of security, meaningfulness, mental resilience, happiness and life satisfaction. Striving to achieve well-being is the essence of positive psychology, which aims to maximize personal development.

Additionally, well-being is defined as the overall quality of an employee’s experience and functioning at work (Grant et al., 2007; Warr, 1990), which blurs the boundaries between EWB and EX.

Many organizations regard improving employee well-being as a crucial human resources issue. Surprisingly, many organizations view EWB as an incidental component of organizational output rather than a part of the organization’s mission (Inceoglu et al., 2018). Consequently, employees may experience job overload, psychological anxiety, and fatigue while having a number of wellness initiatives at their disposal.

Employee well-being, or lack thereof, has been proven to impact corporate operations and efficiency – it affects costs related to absenteeism, turnover, and discretionary effort (Spector, 1997), organizational citizenship behavior (Podsakoff et al., 2000), and workplace accidents (Danna & Griffin, 1999). On the other hand, the literature shows that increasing psychological well-being of employees shapes their satisfaction with their jobs and lives (Judge & Watanabe, 1993); level of performance (Judge et al., 2001; Nielsen & Noblet, 2018; Wright & Cropanzano, 2000) and quality of leadership (Msuya et al., 2023). Furthermore, the physical well-being of employees influences their health in terms of outcomes such as cardiovascular disease and blood pressure (Danna & Griffin, 1999). Additionally, the social well-being of employees provides opportunities for interpersonal relationships and involves treating employees with varying degrees of fairness (Kramer & Tyler, 1996). Finally, if HRM fosters employee well-being, it ultimately results in improved operational and financial performance of an organization (Van De Voorde et al., 2012).

Contrary to the mainstream research, Fleming (2024) and Daniels et al. (2022) proved that most well-being interventions do not provide resources in response to job demands or are poorly evidence-based in maintaining workers’ mental health (WHO, 2022).

EMPLOYEE EXPERIENCE

The growing need for improved customer satisfaction as a way to create competitive advantage and commercial gains led researchers to link customer experience (CX) with the quality of employees’ experience (Abhari, 2008; Heskett et al., 1997). That, in turn, prompted further discussion of how employees experience their workplaces and how experiences affect employees’ engagement and thus overall business performance (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009; Zeidan & Itani, 2020; Zelles, 2015). Over the years, both academics and HRM practitioners have attempted to define and frame the concept of employee experience (EX). Plaskoff (2017) introduced EX as a new HRM approach based on the quality of the relationship between an employee and their employing organization, as perceived by the former over the course of their employment. Morgan’s understanding of EX is best described through the lens of employees’ expectations, needs, and desires intersecting with organizational designs, which can be intentionally molded through three environments:

the physical environment, which reflects organization’s values, allows for flexibility and is aesthetically pleasing;

the technological environment, where consumer-grade technology is made available to employees to meet the business requirements of their roles;

the cultural environment, which encompasses variables ranging from the organization’s reputation, its pronounced and evident support of diversity, equity and inclusion, through its managers’ competences to learning and development opportunities.

The foundation of those environments is the organization’s mission, or – as the author puts it – its reason for being (Morgan, 2017).

Maylett and Wride’s (2017) similar conceptualization of EX as a sum of employees’ perceptions derived from interacting with an employing organization highlights the importance of contracts existing between employees and employers. The authors focus on moments of truth – situations in which employees verify whether the employing organization adheres to the contractual obligations, explicit or implicit, existing between them. Positive verification results in alignment of expectations, strengthening employees’ trust in the organization and improving their engagement. On the other hand, any instance of brand, transactional or psychological contract violation leads to distrust and, effectively, disengagement and decline in motivation and satisfaction.

Despite the abundance of seemingly discordant definitions existing in the literature today, a review of the most popular models allows one to extract three basic elements that often compose EX definitions: employees’ expectations, employee-employer interactions and psycho-cognitive consequences of those interactions. The ternary character of most theories also seems to permeate the argument of EX being, in fact, a processual reality, continually renegotiated between employees and their employing organization (Cornelius et al., 2022), and thus not belonging to either of them.

Yet, the malleability of employees’ experiences encourages a design-oriented perspective that can also be observed in the literature. Namely, if elements of work and career affect an employee’s cognition, affection and behavior (Abhari, 2008), the mere potential urges one to construct those elements meticulously in order to secure positive reinforcement of employees’ development, contribution and engagement, which in turn would allow organizations to retain their workforces for longer (Itam & Ghosh, 2020). That strong belief in the stimulating power of aforementioned career elements has led authors such as Bersin et al. (2017), Maylett and Wride (2017), Plaskoff (2017), and Tucker (2020) to turn to Design Thinking (DT) as the recommended approach for designing and implementing EX. DT methodology is often presented in the literature as a means to ensure that employees’ needs, wants, and expectations constitute the focal point of contemporary HRM models and strategies (Chomątowska et al., 2019), yet scientific validation of the effective application of Design Thinking tools (e.g. personas or employee journey mapping) within HRM is still scant.

RELATIONS BETWEEN EMPLOYEE WELL-BEING AND EMPLOYEE EXPERIENCE

The literature on the subjects of EX and EWB has been growing, especially since 2019, when the COVID-19 pandemic strongly impacted the areas of health, mainly occupational health and mental health in social science disciplines. Even though newer research is emerging, the idea of considering and comparing those two issues is rather scarce. Except for Batat (2022), who combines the two issues together, showing that well-being is the driver and the outcome of overall EX, Chaudhari et al. (2023), who claim that positive job experience provides well-being, Shambi (2021), who suggests that investing in occupational health and increasing well-being is part of improving EX, and finally Das and Dhan (2023), who argue that well-being is connected to EX only in organizational and HRM literature (without details), the majority of papers do not look for similarities and differences in either theoretical or practical perspectives. However, these two issues are often investigated in relation to work engagement, satisfaction, performance, productivity, turnover, and attrition, as well as HR practices, HRM or HR transformations.

Although the analysis of models and approaches in the scientific literature showed the blurry boundary between the two theoretical constructs, EWB is more focused on current emotional states or assessments of life domains, whereas EX seems to highlight the dynamic interplay between employees and employing organizations and connects employees’ psychological states with their expectations of organizational environment.

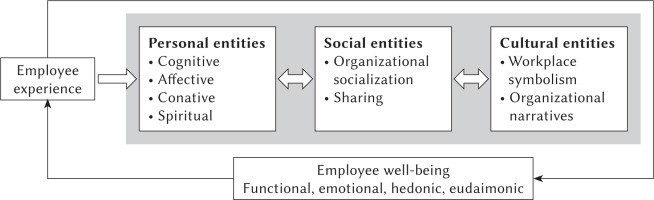

Batat’s (2022) investigation of the relationships between EX and EWB presented the latter as considered both a driving force and an outcome of the overall EX. According to the author’s “Employee experience framework for well-being”, there are three entities (personal, social and cultural) which should be considered to develop a better understanding of interchangeable relationships between those two constructs (Figure 1).

Moreover, Batat suggests that organizations should examine two main approaches – iterative and holistic – in designing a sustainable EX to secure employee well-being. It means taking into account multiple factors (personal, social and cultural) within and outside of an organization. The crucial fact is that an employee’s subjective perception of the organizational environment, in contrast to performance or individual efficiency, determines the quality of experiences and its impact on employee well-being.

Table 1

Differences and similarities between EX and EWB

[i] Note. Own compilation based on Abhari, 2008; Bersin et al., 2017; Cornelius et al., 2022; Dagenais-Desmarais & Savoie, 2012; Deci & Ryan, 2008; Diener, 1984; Grant et al., 2007; Hesketh & Cooper, 2019; Itam & Ghosh, 2020; Johnson et al., 2018; Maylett& Wride, 2017; Morgan, 2017; Plaskoff, 2017; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Searle, 2008; Seligman, 2018; Van De Voorde et al., 2012; Waterman et al., 2010; Yohn, 2018; Zeidan & Itani, 2020. EWB – employee well-being; EX – employee experience.

This perspective reveals the need for total and comprehensive change in strategic foresight and practices of HRM. It means moving from a functional approach, where performance and productivity of employees are linked to well-being, to an experiential or more comprehensive perspective where individual values are fulfilled (Batat, 2022) and sensory, affective, cognitive, physical and social experiences are created (Lipka, 2022; Schmitt, 2010). After a thorough analysis of definitions and aspects of EX and EWB, we summarized them in Table 1.

The above comparison does not exhaust all possible relationships between employee experience and well-being. It draws lines between the two issues that might be perceived in the scientific literature and between practitioners as well. It delivers the answers to the first research question due to establishing the main theoretical approaches defining the two concepts in a partly similar way through satisfaction, engagement, and overall assessment of one’s “impression” towards “self” at work. Even though there are blurred boundaries between these two concepts, the differences are significant. While well-being is the assessment of one’s own condition (mental, physical, social), EX is a dynamic assessment of the relation between the subject and their employer/organization. Well-being thus focuses more on the assessment of the current state, whereas EX is directed towards expectations for the future based on past observations. Finally, a person’s evaluation of one’s own well-being extends beyond the organizational environment and includes private life and its relations with work life (e.g. work-life balance), whereas employee experience focuses only on the working environment.

Theoretical considerations on the two concepts have led many authors to some practical conclusions that may ease effective applications in practice. Therefore, the way in which the two constructs are understood and applied in companies was the core of the survey research among HR practitioners that is described below.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

MEASURES

A specially designed survey was created to investigate how the concepts of EWB and EX are understood by practitioners as well as to explore their responsibility and ways of implementing initiatives related to those issues. The survey was directed at professionals broadly responsible for investigating EWB and EX initiatives. The questionnaire, consisting of 10 questions/statements, addressed the stated research questions. Five of the questions/statements were related to the second research question – the understanding of EWB and EX phenomena by practitioners and ways of their implementation. The examples of statements were as follows:

E.g. 1. Which of the definitions below matches your understanding of employee experience (choose the most suitable statements)?

overall impression of psychological, physical and social environments at work

overall satisfaction with professional and private life

evaluation of one’s own achievements, capabilities, needs and ways of working

sense of meaning and fulfilment at work and in personal life

comparison of one’s own achievements with expectations regarding them

the feeling of mutual person-organization fit

set of practices and rules designed to improve employee motivation and engagement

motivation and engagement stimulating power

evaluation of company initiatives aimed at improving employee engagement and satisfaction

The same statements were used to match the understanding of employee well-being.

E.g. 2. Do you have separate initiatives addressing well-being and employee experience? Select one answer.

yes

no, these are the same initiatives

we don’t have any initiatives addressing well-being or employee experience

The responsibility for implementing EWB and/or EX initiatives was established by 3 items. The examples are as follows:

E.g. 3. Who is responsible for initiating employee experience initiatives? Select all that apply.

employee(s) of the HR department

dedicated EX expert or team

volunteering employees

the company board or the owner

The same statement was used to match the understanding of employee well-being.

E.g. 4. To what extent do well-being and employee experience initiatives impact your individual performance evaluation? Select one answer.

They are essential to my performance evaluation

They are considered but not essential to my performance evaluation

They have a limited impact on my performance evaluation

They have no impact on my performance evaluation

Finally, the types and goals of initiatives that are delivered in terms of EX and EWB were measured by 3 items. The examples are:

E.g. 5. What are the main goals of well-being initiatives held in your company?

sustaining employees’ health

boosting employee motivation

improving employee performance

limiting voluntary leaves

strengthening employer brand

improving employee engagement

improving employee satisfaction

Possible answers included: “essential”, “very important”, “quite important”, “of little importance”, “irrelevant”.

The same question was posed to investigate the goals of employee experience initiatives.

Different ways of answering and different scales were applied in the survey. In two items respondents had to choose one answer among all statements (as in E.g. 2 and E.g. 4); in five other items, respondents were able to choose more than one answer among a set of statements (as in E.g. 3); and finally, in three items, respondents were asked to put the statements in order or a hierarchy of importance from most important to least important (as in E.g. 5).

Additionally, four demographic items were added, considering job position, current job tenure in a role, and respondents’ enterprise characteristics – size and sector (according to the Global Industry Classification Standard – GICS). The establishment of the last version of the questionnaire was thoroughly discussed to cover two main drivers – collecting answers for research questions and creating a tool which is as short as possible (not longer than 10 minutes) in order not to discourage the respondents from completing the questionnaire.

A questionnaire was purposefully designed for this study. Three independent experts assessed all statements to adjust them to the research questions and make them readable to respondents.

DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES

The computer-assisted web interview (CAWI) technique applied in the research involved a respondent filling out an online version of the questionnaire. An online link to the survey was provided. Survey links were sent to twelve different forums for HR professionals, using a social platform (LinkedIn). The link to the online survey was accessible for a period of 5 weeks. Through the snowball method we reached 41 experts who voluntarily filled in the survey. It took the respondents up to ten minutes to fill in the questionnaire. Although this was not designed as a randomized controlled trial (RCT), participants were purposefully selected and approached to enable us to gather as reliable information about practices of EWB and EX in their companies as possible, as participants were confirmed to be representatives of HR departments. Respondents could voluntarily provide their e-mail addresses if they were interested in receiving a published version of the research findings, once made available.

DATA ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistica 13.3 version. In order to answer scientific questions provided in the paper, descriptive statistics were used, including measures of central tendency (mean, median), variability (standard deviation) and frequency distribution (count). Apart from the univariate approach, using cross-tabulation (e.g. Table 2) enabled us to evaluate relationships between two variables.

SAMPLE DESCRIPTION

We received 41 properly completed questionnaires. Table 2 presents the characteristics of establishments and respondents in our sample.

Table 2

Characteristics of the research sample in the crosssection of selected quality features

Since the research did not include a medical or clinical component, it falls outside the typical scope of research that requires ethical approval. Nonetheless, our study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which safeguards the rights of participants. Their participation was entirely voluntary and anonymous. Anonymity was assured in the introduction to the survey, and subjects were recruited voluntarily and provided informed consent before participating. They were fully informed about the purpose of the study and the methodology for data utilization.

RESULTS

Regarding the understanding of the EX and EWB, we asked the respondents first if the concepts of EWB and EX are equal or different in their opinion. When they chose the second answer, we provided them with the nine most common definitions and requested them to choose which of those are related to the employee experiences and which to well-being. We also asked them how often they launch initiatives aimed at those two issues. Definitions relating to well-being were as follows:

overall impression of psychological, physical and social environments at work

overall satisfaction with professional and private life

evaluation of one’s own achievements, capabilities, needs and ways of working

sense of meaning and fulfilment at work and in personal life

Employee experience was defined by the five following statements:

comparison of one’s achievements with expectations regarding them

the feeling of mutual person-organization fit

set of practices and rules designed to improve employee motivation and engagement

motivation and engagement stimulating power

evaluation of company initiatives aimed at improving employee engagement and satisfaction

Thirty-six out of 41 respondents (88%) indicated the differences between the two concepts, and only two (5%) respondents acknowledged them as identical. Three (7%) admitted they did not know or use these terms. According to Table 3, the most common understanding of EWB among practitioners is quite similar to how it is defined in theory. The majority of respondents pointed to overall satisfaction, sense of meaning and fulfilment and overall impression with aspects of job environment as three out of four assumed definitions of well-being.

The most popular definition of EX according to practitioners – the overall impression of psychological, physical and social environments at work – happens to also define well-being according to the literature. The following three definitions chosen by respondents corresponded more closely with the common understanding of EX in the scientific literature: the experience or evaluation of the company; initiatives increasing engagement and satisfaction; and person-environment fit (Table 3).

In general, it is concluded that understanding of the two concepts among HR professionals is more similar to the academic discourse in the case of well-being than in the case of employee experience. However, definitions ascribed to one construct are still used to depict the other one by every fifth respondent, which proves the blurriness of the two concepts among many practitioners. Moreover, the noted differences do not seem to transfer to initiatives undertaken by practitioners; 8 out of 34 respondents admitted that they did not have separate initiatives for EX and EWB (see Table 4) despite stating that the two are distinct concepts.

The second research question covered not only the way in which HR experts understand the issues of EX and EWB but also how they implement initiatives related to them. Table 4 presents the characteristics of initiatives addressing EWB and EX, and the frequency of their implementations. It shows that companies where the two constructs are understood as discrete launch regular initiatives (e.g. a wide offer of benefit packages) and invest in ongoing, permanent supporting EX or EWB.

The third research question considered the responsibility for implementing and managing EWB and EX in the company. The results showed that HR departments hold primary responsibility for implementing such initiatives in the majority of cases and close to exclusive responsibility over EX initiatives (74%). In the case of EWB, 37% of respondents pointed to two responsible subjects, and less than one in ten cases engaged three or more subjects to implement well-being initiatives. Processes for managing EX are even more centralized in the HR departments (see Table 5). The results also showed that volunteers selected from employees are quite often (in 40% of cases) the subjects responsible for implementing EWB initiatives together with a dedicated well-being team or HR specialists. In the case of managing EX initiatives, mostly HR specialists, together with a dedicated EX team, are liable for implementations, which is an interesting finding in light of most popular EX models postulating that experience is dependent on employees’ interactions with various work environments, some of which – e.g. technological, as proposed by Morgan (2017) – may not be within HR departments’ scope of influence.

The last research question in the present study considered the types of initiatives and their objectives. Seven out of 41 questionnaire respondents admitted that the goals of EWB initiatives are different than the goals of EX actions, whereas the majority (31 respondents) acknowledged the same objectives for both EWB and EX activities. Respondents were offered a list of seven key goals, according to the literature, and were asked to arrange them in a hierarchical order, representing their importance from an employer’s perspective. Each position on the hierarchy was assigned a point on a scale – from 7 (the most important) to 1 (the least important). Table 6 presents the median value for the group of respondents that admitted the same goals for both types of initiatives.

Table 3

Characteristics of understanding of EWB and EX in the research sample

Table 4

Understanding of the EWB and EX concepts vs. frequency of initiatives

The results show that improving employee satisfaction and improving engagement are the most important goals of initiating EX as well as EWB initiatives. It implies that even if improving health and well-being is the core of EWB activities, practitioners pay more attention to achieving a higher level of satisfaction, engagement and even motivation among their staff, which might be easier to measure and observe in employees’ behavior.

The respondents who acknowledged different aims towards EX and EWB indeed created different orders in their hierarchies. The most important goals for EWB initiatives were improving or sustaining employees’ health and increasing their satisfaction (both medians 6.00) and for EX practices the main aims were strengthening the employer brand (median 7.00) and limiting the number of voluntary leavers (median 6.00); unfortunately, the group of respondents was too small (n = 7) to consider the result as significant.

Table 5

Responsibility for implementing EWB and EX initiatives within the organization

Table 6

Characteristics of goals of EX and EWB initiatives

Table 7

Approach to EWB and EX related to investments in the cross-section of researched sample

Finally, we asked HR practitioners about the approach to investment in both types of activities. Some core examples of these activities were proposed with the division into investing in activities for a particular group or all employees, not investing at all or limiting their involvement to encouraging employees to partake in voluntary activities inside or outside the organization. The results showed that the highest investments are made in vocational (job-related) skills development (n = 38, 100%), physical health and comfortable working conditions (n = 35, 92%), interesting job content and mental health (n = 28, 74%), social relations (n = 27, 71%) and fun and pleasure at work (n = 25, 66%). Financial well-being education (n = 26, 66%) was proved to lack employers’ interest, with over 55% of responding subjects reporting no investments in such initiatives. Quite low investment was also indicated within the activities related to volunteering (n = 15, 39.5%). The detailed results are shown in Table 7.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Despite the differences in EX and EWB in the scientific literature, the two concepts interpermeate and influence each other, especially in the organizational environment. The in-depth investigation of the mechanisms at work for creating and maintaining them helps in understanding their mutual penetrability.

Through this paper we aspired to bridge the gap observed in the scientific literature of EWB and EX and to investigate the application of academic knowledge among practitioners. Four main research questions were intended to advance the analysis of the relation between EWB and EX. The first question aimed to improve the understanding of EWB and EX theories alignment. The literature review presented in the first part of the article allowed us to establish the main theoretical approaches defining the two concepts and conclude that, despite blurred boundaries, the two concepts differ significantly. Inasmuch as well-being is the assessment of one’s current mental, physical, and social states, EX is largely presented as an ongoing validation of the employee-employer relation built upon the intersection of the employee’s expectations and the employer’s offering to meet those expectations. Furthermore, it is observed that a person’s evaluation of their own well-being extends beyond the organizational environment and percolates through private life aspects to result in a work-life balance, whereas employee experience focuses only on the working environment (Batat, 2022; Johnson et al., 2018). The results of our exploratory study of the differences between EWB and EX also imply that well-being is already better grounded for practical actioning than employee experience, with standardized measurements available (e.g. WellBQ; NIOSH, 2024) and a growing number of regulatory requirements related to the issue (WHO, 2022).

The empirical study conducted on the basis of a custom survey distributed among HR professionals confirmed that the two concepts – EWB and EX – exist as discrete issues in organizations. The analysis of 41 responses proved that well-being is understood as the overall satisfaction with professional and private life, encompassing the sense of meaning and fulfilment at work and in personal life, whereas EX is primarily viewed as the overall impression of psychological, physical and social environments at work. The results also provided evidence that despite the discreteness of the concepts, both EX and EWB initiatives, launched and managed primarily by the HR departments independently, aim primarily at improving employee satisfaction and engagement. Even though the literature places improving health and well-being at the core of EWB activities (Hasson & Butler, 2020; Hesketh & Cooper, 2019; Nielsen & Noblet, 2018; WHO, 2022), our study proves that practitioners tend to pay more attention to achieving a higher level of satisfaction, engagement and motivation among staff. It is further concluded that most companies invest in permanent and interim yet regular initiatives creating and maintaining well-being and employee experience through vocational skill development (100%), physical health promotion and comfortable working conditions (92%), interesting job content and mental health (74%), and social relations (71%). Three aspects identified as factors of positive influence on well-being and experience that receive the least investment among the researched companies are financial well-being education (66%), fun and pleasure at work (66%) and volunteering activities (39.5%). These findings correspond with previous studies, which showed that the most frequent investments consider initiatives promoting healthy organizational culture as well as psychological counselling (Molek-Winiarska & Molek-Kozakowska, 2020). Also, as shown by Holman et al. (2018), investing in skills (particularly in stress-management skills) seems more effective than implementing ergonomics or redesigning job content; however, the effects of the latter may be delayed (Leka et al., 2014; Nielsen & Noblet, 2018).

We acknowledge that this study has some limitations. The main one stems from both the size and characteristics of the research sample. Firstly, the number of business entities constituting the research sample is too low to be able to draw general conclusions. Secondly, the research encompassed only organizations operating in Poland. Apart from that, the method used in the research relies heavily on respondents’ opinions, which could increase the level of subjectivity and, as a result, distort some of the data acquired in the process. Hence, the research results presented in the paper build a theory that needs to be tested empirically in further research. Specifically, apart from the quantitative approach, qualitative research should be applied, involving an in-depth analysis of the described phenomena and (potential) causal relationships. We are going to continue exploring the topic of relationships between employee experience and well-being in future projects involving more numerous study samples and also qualitative methods of research in order to advance the scientific literature of EX and EWB and to provide further insights for practitioners.