BACKGROUND

In the past decades, considerable attention has been directed to the evaluation of patients’ quality of life (QoL) about their health status (health-related QoL or HRQoL). The World Health Organization (WHO) defined QoL as “the individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” (WHO, 1995). Accordingly, the emphasis shifted from the context of the objectively definable functional status to the subjective well-being (Cohen, 1982; De Girolamo et al., 1995). This definition is particularly relevant in the case of patients with chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCD; Megari, 2013) as they frequently report impaired performance in physical tasks, lower HRQoL, and higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Among CNCD, asthma represents a serious health problem that affects approximately 300 million people of all ages worldwide and causes 250,000 deaths annually (Croisant, 2014; Nunes et al., 2017). Based on existing data, the WHO estimated that the number of people with asthma will increase by 100 million by 2025. These data highlight the urgent need to accelerate interventions aimed at minimizing morbidity and its associated human and financial costs (Bousquet & Kaltaev, 2007). Based on a report of an international cross-sectional study that involved 8,111 patients, disease control remains suboptimal in a large proportion of patients (56.5%) (Braido et al., 2016; Cazzoletti et al., 2007; Cottini et al., 2021; de Marco et al., 2003; Partridge et al., 2006; Peters et al., 2007). The causes include some psychological aspects that make the management of the disease even more complex. For instance, in cases of patients with severe asthma, psychological factors may affect the patient’s perception of the disease, symptom interpretation, and treatment adherence (Baiardini et al., 2015; Foster et al., 2017). On the other hand, the presence of poorly controlled, severe asthma may influence mental health, as demonstrated by the high prevalence of anxiety disorders and psychological symptoms in these patients. These data underlined the relationship between physical and psychological symptoms (Baiardini et al., 2015; Lehrer et al., 2002; Vazquez et al., 2017; Weiser, 2007). In this context, implementation of the assessment of mental symptoms and psychological aspects in patients with asthma may help in planning appropriate interventions to improve disease control and patient well-being (Baiardini et al., 2015). The standard parameters for the evaluation of severity and disease control, such as spirometry, drug use, symptoms severity, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness, provide precious information on the respiratory function but little on the functional limitations (physical, emotional, and social) playing a central role in the daily life of both pediatric and adult asthmatic patients.

Furthermore, psychological stress is a risk factor for the onset of asthma in adults. More specifically, high levels of stress are associated with a two to three times greater risk of developing the disease than low levels of stress. In particular, stressful life events most associated with the development of asthma later on in life are family illnesses, divorces or separations, and conflicts in the workplace (Lehrer et al., 2002).

In light of these considerations, we evaluated different clinical and psychological factors in adults with allergic asthma at the time of diagnosis and assessed their impact on patients’ perception of HRQoL. The authors hypothesized that patients with asthma might exhibit clinically significant psychological symptoms (anxiety, depression, somatizations, and hostility at the Symptom Questionnaire – SQ) as well as personality traits known to be related to anxiety disorders. The aim was to investigate the psychological factors associated with the asthmatic disease at the time of diagnosis to describe the factors predisposing and/or involved in the exacerbation of the physical disease. Patients were recruited at the time of diagnosis to exclude possible variables related to psychological distress resulting from awareness and long-term living with the disease. More specifically, the objectives that guided the research were: to analyze the psychological status of patients with asthma (descriptive statistics of symptoms, behaviors and lifestyle at risk for stress-related disorders, personality traits, and quality of life); to verify if there were significant differences between males and females in the psychological tests – SQ, 16-Personality Factor Questionnaire (16-PF), and P Stress Questionnaire (PSQ); to describe the correlations between Rhinasthma and age and the other questionnaire scores (SQ, 16-PF, and PSQ).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study design was exploratory and cross-sectional. Sixty patients with allergic asthma (32 females and 28 males), aged between 18 and 55 years (mean age = 29.4), were consecutively recruited. The data were collected by a psychologist and a pneumologist-allergologist of the Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology of the Hospital of Lecce (Italy) while the patients were attending the first or second visit at which they received the diagnosis of asthma. For this reason, the patients were not yet taking any type of drug for the pharmacological control of their pathology. The criteria for inclusion in the study were age > 18 years; diagnosis of allergic asthma without comorbidities; no known psychological problems; and not receiving psychological/psychiatric or psychopharmacological treatment at the time of the visit.

This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the local ethics committee at the Hospital of Lecce.

All procedures were conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and its later advancements, by the research involving human participants. Subjects’ anonymity was preserved, and the data obtained were used solely for scientific purposes. All patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable.

No false feedback were given and no potentially harmful evaluation methods were used. Participation was voluntary, and participants could drop out at any time without any negative consequences.

MEASURES

Patients were taken to a quiet room and were informed by a research assistant about the study procedures. After providing informed consent, patients completed the following questionnaires.

The Italian version of theSymptom Questionnaire (SQ; Fava et al., 1983), a yes/no questionnaire, was used to easily self-rate psychological distress. It contains four scales based on the factorial analysis of the psychological symptoms of anxiety (A), depression (D), somatization (S), and hostility (H). Each scale can be divided into 2 subscales, one concerned with symptoms and the other with well-being, for a total of 8 subscales. Therefore, each of the main scales includes items from both the symptoms and the well-being subscales. The clinical cut-off corresponds to 4 for all the scales of the test. The SQ was demonstrated to have high sensitivity and specificity levels (80% and 76% in general practice, respectively; 86% and 74% in hospital medical wards; and 83% and 85% in emergency departments (Rucci et al., 1994). These qualities make this instrument particularly appropriate, not only for the initial assessment of the patients’ complex clinical profiles but also for a possible re-test of the self-reported symptoms over time (Benasi et al., 2020). This test has weekly, daily, and hourly versions. For the purpose of this research, the weekly version was used. The SQ was re-administered three months afterward during a check-up.

Cattell’s16-Personality Factor Test (16-PF; Cattell, 1956) was used to assess the personality of participants. This instrument is composed of 105 items, with three possible responses, that identify 16 primary, bipolar, and relatively independent factors. The 16 dimensions identified are: A – warmth, B – reasoning, C – emotional stability, E – dominance, F – liveliness, G – rule-consciousness, H – social boldness, I – sensitivity, L – vigilance, M – abstractness, N – privateness, O – apprehension, Q1 – openness to change, Q2 – self-reliance, Q3 – perfectionism, Q4 – Tension. Raw scores are converted into stanine or standard-nine scale, ranging from 1 to 9. Scores between 3 and 7 are considered average. In addition to these primary factors, which constitute the fundamental traits of personality, the test provides a validity scale. Cronbach’s α falls between .69 and .75 in all the various international standardizations.

TheP Stress Questionnaire (PSQ; Pruneti, 2011)is a tool made up of 32 items, grouped into six scales: sense of responsibility (SR), vigor (V), stress disorders (SD), precision and punctuality (PP), spare time (ST), and hyperactivity (H). It detects whether there is a present risk for stress-related physical disorders attributable to some characteristics of the personality configuration known as “type A behavior”. More specifically, the SR factor includes items related to specific attitudes such as taking life and personal duties too seriously (maintaining a level of continuous engagement in working or doing other activities). The V factor includes items that refer to the feeling of having characteristics such as vitality, energy, and stress resistance. The SD factor consists of items linked to troubles and problems usually related to stress reactions, such as a lack of sexual interest and difficulty falling asleep. The PP factor is made up of items that are relevant to behaviors characterized by spitefulness, precision, and punctuality. The ST factor is linked to items regarding the care of oneself, and the capability and possibility of relaxing and taking breaks from work. The H factor refers to behaviors characterized by extreme activity and the presumption of being able to resist fatigue well. The Cronbach’s α falls between .39 and .70 for all the various factors that compose the instrument. Stanine scores have a distribution between 1 and 9, with a mean of 5 and a standard deviation of 1.96.

TheRhinasthma questionnaire (RQ; Baiardini et al., 2003) is a 30-item psychometric tool covering the main symptoms and problems related to respiratory allergy, specifically designed to easily assess the HRQoL of adult patients with rhinitis, asthma, or both. Patients are asked to rate how much they were disturbed by rhinitis and asthma symptoms in the two prior weeks on a four-point scale from 1 (not important) to 4 (very important). Higher scores represent a worse perception of HRQoL. There are four dimensions involved: LA – lower airways, related to asthma; UA – upper airways, related to rhinitis; RAI – respiratory allergy impact, including the impact of both diseases; GI – global impact on the QoL.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 28.0.1.0). From the obtained data means and standard deviations of the scores obtained from the total sample in the SQ, 16-PF, PSQ, and Rhinasthma scales were calculated. Tests for skewness and kurtosis and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were used to determine the normality of distribution. Since the assumption of normality was not respected, the following analyses were computed: (1) the Wilcoxon test was used to compare pre-post scores of the sub-scales of the SQ scores of the total sample; (2) the Mann-Whitney U test was calculated to compare the scores of the tests (SQ, 16-PF, PSQ, Rhinasthma) between male and females; (3) Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to describe the relation between the scales of the Rhinasthma questionnaire and age, symptoms (SQ), personality traits (16-PF), and tendency to adopt lifestyle at risk for stress-related physical disorders (PSQ).

RESULTS

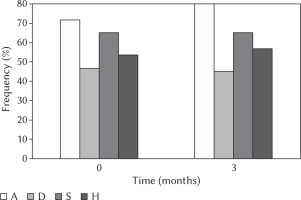

Overall, in all four scales of the SQ (A, D, S, H) patients presented average values higher than the cut-off both at baseline and after 3 months (Figure 1). For instance, the average baseline score was 71.7% for scale A, 46.7% for scale D, 53.3% for scale H, and 65% for scale S (Figure 1). Furthermore, the Wilcoxon test did not show significant differences between the sub-scales of the SQ at the 3-month follow-up compared to baseline, which means that the scores remained above the cut-off values.

Figure 1

Frequency of patients with scores higher than the cut-off for the scales of anxiety (A), depression (D), somatic symptoms (S), and anger/hostility (H) at baseline (time 0) and after 3 months of follow-up

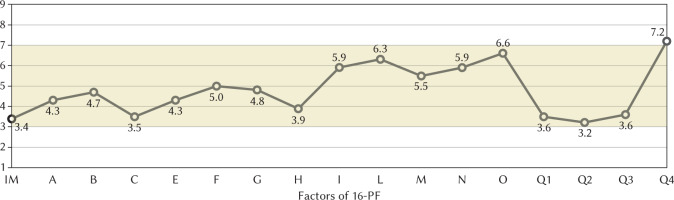

Furthermore, this research assessed the personality traits in asthmatic patients through the 16-PF. This tool was administered only at baseline. As shown in Figure 2, patients obtained stanine scores at the edge of the typical range (considered between 3 and 7) for the following factors: emotional stability (C), social boldness (H), openness to change (Q1), self-reliance (Q2), and perfectionism (Q3). The validity scale (Image Management, IM) showed a low value of 3.4, indicating infrequent attempts to falsify answers. Additionally, stanine scores above the average were recorded for the factor of tension (Q4).

Figure 2

Representation of the mean scores of the 16-PF of the sample on a standard-nine scale, ranging from 1 to 9

Note. 16-PF – 16-Personality Factors Questionnaire. The 16 dimensions identified, in addition to the validity scale (IM), are: A – warmth; B – reasoning; C – emotional stability; E – dominance; F – liveliness; G – rule-consciousness; H – social boldness; I – sensitivity; L – vigilance; M – abstractness; N – privateness; O – apprehension; Q1 – openness to change; Q2 – self-reliance; Q3 – perfectionism; Q4 – tension. Scores between 3 and 7 are considered average.

As regards the behavior and lifestyle at risk for the onset of stress-related disorders, the PSQ results are summarized in Table 1. The mean values obtained were within the normal range.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of the P Stress Questionnaire and the Rhinasthma questionnaire (N = 60)

Considering the results of the Rhinasthma questionnaire, there emerged a certain degree of HRQoL impairment (Table 1); in particular, the LA dimension values were higher than those of UA.

For all of the psychological tests (SQ, 16-PF, and PSQ), the Mann-Whitney U test was conducted considering gender as an independent variable, although significant differences did not emerge between the given factors. Spearman’s correlation analysis between RQand age and the other questionnaire scores was performed. Results are summarized in Table 2. Notably, the UA dimension, more related to rhinitis, displayed only one correlation (with the V factor). Considering age, older age significantly correlated with higher scores of the LA, RAI, and GI dimensions. Looking at the psychological symptoms, all four scales (A, D, S, and H) correlated with a worse perception of HRQoL. Furthermore, similar results were obtained with the SQ scores at baseline and after three months. As concerns personality traits, a correlation was observed between the factors IM (inverse), C (emotional stability; inverse), G (rule-consciousness), I (sensitivity), O (apprehension), and Q4 (tension) and the perception of HRQoL of asthmatic patients. Lastly, a significant correlation was observed between V and SD (inverse) and asthmatic patient HRQoL perception.

Table 2

Spearman’s correlation analysis between the clinical variables investigated

[i] Note. 16-PF IM – 16-Personality Factors Questionnaire, Image Management; 16-PF C – 16-Personality Factors Questionnaire, Emotional stability; 16-PF G – 16-Personality Factors Questionnaire, Rule-consciousness; 16-PF I – 16-Personality Factors Questionnaire, Sensitivity; 16-PF O – 16-Personality Factors Questionnaire, Apprehension; 16-PF Q4 – 16-Personality Factors Questionnaire, Tension; PSQ V – P Stress Questionnaire, Vigor; PSQ SD – P Stress Questionnaire, Stress disorders; SQ A – Symptom Questionnaire, Anxiety; SQ D – Symptom Questionnaire, Depression; SQ S – Symptom Questionnaire, Somatization; SQ H – Symptom Questionnaire, Hostility; RQ – Rhinasthma questionnaire; *p < .05; **p < .01.

DISCUSSION

Our findings confirmed the frequent presence of an above-average level of psychological distress, specific personality traits, and impaired HRQoL perception in patients with allergic asthma. Notably, no stress-related behaviors were observed with the PSQ.

The coexistence of asthma and psychological disorders, such as depression and anxiety, has been extensively reported although the data fluctuate according to disease severity, patient age, and the screening test employed (Dudeney et al., 2017; Porsbjerg& Menzies-Gow, 2017; Shankar et al., 2019; Weiser, 2007). In our population, the percentages of patients with symptoms of anxiety and depression were 71.7% and 46.7%, respectively, at the first visit and 80.0% and 45.0% respectively, after three months. Due to the close relationship between psychological symptoms and asthma, as well as the psychological triggers of the disease (Vazquez et al., 2017), it is important to evaluate the psychological status of these patients. The critical role of depression and anxiety as possible contributors to symptoms is also acknowledged in the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) report, along with poor QoL, and sometimes poor asthma control. These aspects highlighted the importance of dealing with emotional stress among non-pharmacological treatments and underlined the importance of mental health assessment for patients with stress-related physical disorders (Rothe et al., 2018). Unfortunately, depression and anxiety are often overlooked in chronic diseases as they are expected conditions. However, their presence may affect treatment adherence and lead to poorly controlled disease. As a result, frequent exacerbations and sequelae may be recorded as well as decreased survival and greater consumption of healthcare resources (Carli et al., 2021; Corrao et al., 2016; Holmes & Heaney, 2021; Mäkelä et al., 2013). Indeed, presence of psychological distress, female gender, older age, and cognitive impairment are known as predictors of low compliance with therapy (Colivicchi et al., 2010). In addition, compliance with therapy is estimated to be below 50% in asthma patients (Gillisen, 2007). Therefore, promoting interventions to increase therapeutic adherence may be important for improvement of the patients’ health. Disease management and control could be implemented by psychological counselling or psycho-educational interventions as part of an integrated care pathway. This care concept would have a positive impact on QoL and healthcare costs (Pinnock et al., 2017; Powell & Gibson, 2003). Nonetheless, asthma education and self-management are included as key recommendations in the asthma management guidelines (Rothe et al., 2018). In particular, self-monitoring of symptoms and regular meetings with a clinician are acknowledged as part of a training program to promote self-management (Gibson et al., 2003; Rothe et al., 2018).

Moreover, asthma is also strongly associated with panic disorders, because stressful episodes may interfere with breathing, thus leading to broncho-constriction (Vazquez et al., 2017). However, it is often difficult to establish whether emotions are the causes or effects of respiratory symptoms, especially if patients tend to mask emotional stress with somatic symptoms. Concerning our population, somatic symptoms were reported in 65% of patients, both at baseline and after 3 months. These clinical manifestations appeared to be mainly connected to HRQoL perception. Therefore, it would be interesting to assess the presence of hypochondria, somatization, or psychosomatic components in patients these features.

In brief, it seems possible to hypothesize the actual existence of a psychological component capable of influencing asthmatic pathology, at least in terms of severity and/or intensity of the physical symptoms. The results of this study underlined that stable personality traits are also involved. In particular, specific factors such as C and Q4 (emotional stability and tension, respectively) are suggestive of vulnerability to the onset of psychopathological disorders, including psychosomatic diseases and stress-related physical disorders (Ebstrup et al., 2011; Guidotti et al., 2022; Pruneti & Guidotti, 2022a; Wang et al., 2014). In the present research, traits such as social boldness, openness to change, self-reliance, and perfectionism were found to be related to HRQoL. More specifically, people who scored low on these scales complained of a greater decline in perceived quality of life. Furthermore, one could also consider the impact of chronic illness on personality. It could be hypothesized that the course of the disease tends to predispose patients to a life characterized by apprehension, prudence, and low openness to new experiences.

Subsequently, interesting aspects emerged observing the relations between HRQoL and other variables. First, in contrast with previous studies reporting that women are more sensitive to disease-related functional limitations and stress (Juniper et al., 1992), no significant differences emerged from the tests administered between genders. Instead, looking at the correlations, interesting aspects emerged. For instance, age was found to be a factor that negatively impacted the perceived quality of life. Getting older accentuated the perception of suffering linked to the pathology. This is probably attributable to the worsening of physical symptoms and related limitations. Even the presence of psychological symptoms seemed to influence the perception of well-being. However, it is also possible that a decline in well-being caused by asthma could correspond to greater psychological suffering in terms of anxiety, depression, somatic symptoms, and hostility. Moreover, a relationship between quality of life and psychological variables emerges when considering personality traits. Specifically, a worse perception of well-being was associated with some personality traits indicative of a tendency to perseverance as well as rigidity. At the same time, sensitivity and apprehension seem to play an equally important role in the deterioration of quality of life. Meanwhile, it emerged that emotional stability had a negative correlation with HRQoL. This aspect highlighted the tendency of these patients to perceive a lack of control over life events that easily causes a loss of psychophysical balance. This attitude is further confirmed by the high score of the Q4 factor that refers to somatic anxiety or the tendency to be easily tense, restless, and unstable.

In a recent review (Miyasaka et al., 2018), the authors explained that psychological stress leads to eosinophilic inflammation of the airways in patients with allergic asthma. This link could be explained by considering the activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system. For instance, some authors even described the interaction between psychophysiological stress, oxidative stress, and neuroendocrine activity with effects on the immune responses of regulatory T cells (Tregs) (Sahiner et al., 2018). Most researchers concluded that it is even possible to consider a “neuropsychiatric phenotype”. This concept includes a set of traits that predispose one to an increase in stress levels and to the onset of specific stress-related physical diseases, such as asthma. However, to our knowledge, this configuration has never been described in detail with psychological measures of personality traits.

Nonetheless, it is possible to hypothesize that a predisposition to mental suffering can generate a worsening of well-being. However, coexistence with the disease and related physical suffering could also have consequences for stable traits, generating a sort of adaptation at the constitutional level. Moreover, this perspective is in line with the relations observed between PSQ and Rhinasthma. In particular, it seems that a high perception of energy levels corresponded to a worsening of the quality of life and lower reporting of psychophysiological symptoms. This aspect could be explained by the perception of illness as highly disabling with respect to the activities that one would like to carry out and the energies that the person expects to have.

However, the main limitations of this study, which are the small sample size and the use of non-parametric tests, did not make it possible to attribute a causal role to personality or quality of life. In the present research, it was considered important to observe the trend between these variables so far little studied in the literature. Indeed, the impact of the disease on mental health could be investigated, possibly considering the severity and intensity of physical symptoms. At the same time, it might also be useful to investigate the inverse relationship, that is to describe the impact of the psychological component on the course and clinical manifestations of asthma. This description might be worthwhile because the bidirectional link between mind and body is well known, especially if the focus is on anxious-depressive symptoms and the immune system. Recent scientific literature (Hashimoto et al., 2010; Höglund et al., 2006; Montoro et al., 2009; Pruneti & Guidotti, 2022b; Uhlig et al., 2019) explained the close link between the stress response, immune system, and some allergic reactions. Considering personality, it might be interesting to define its causal role on the perceived quality of life, for example highlighting stable traits that favor a pessimistic view of the medical conditions and a lower acceptance of relative limitations. However, only parametric statistical analyses could define how much the disease can change stable traits. Both of these hypotheses could be confirmed because factors such as openness to change, self-reliance, and emotional instability could favor poor adaptation to the disease, but they can be negatively influenced by illness as well.

It is hoped that future studies will be able to confirm these results and define the predictive value of psychological factors on the state of health, or vice versa. This would facilitate a better understanding of the progress of the asthmatic disease and its predictors in addition to those already described (age, BMI, smoking, etc.). Moreover, it would be interesting to evaluate the effect of antidepressants as an integrated treatment on patients with asthma and the impact of certain personality traits on treatment adherence.

Beside the limitations, the present study has some strengths. For instance, it comprehensively assessed the psychological status of treatment-naïve patients with allergic asthma through different validated questionnaires and evaluated the association with the patient perception of HRQoL.

CONCLUSIONS

Although preliminary research, the authors would like to underline the importance of multidisciplinary and multidimensional management where the clinical-medical evaluation is supplemented by a psychological investigation. The impact of stress, certain personality traits, and specific psychopathological tendencies on organic diseases such as cardiovascular events (Bonaguidi et al., 1996; Miličić et al., 2016), malignancies (Ciarrochi et al., 2011; Cosentino et al., 2018; De Vincenzo et al., 2022), and neurodegenerative disorders (Kallaur et al., 2016; Morris et al., 2018) has already been analyzed. However, medical wards that benefit from the presence of mental health professionals are still few. It would allow early detection of signs or symptoms of psychological distress and prevent consequences for psychological well-being. Finally, an accurate assessment of mental state and individual stable traits could detect those psychological factors that are identified as risk factors for physical complications. To conclude, as the patient’s perception of health status is the most important indicator of therapeutic success, HRQoL assessment represents an optimal tool to establish treatment efficacy and level of compliance and collaboration with the physician, as well as to monitor patients in the long term.