BACKGROUND

Problematic sexual behaviour (Aaron, 2012) has been described in the scientific and clinical literature using a variety of terms, including sex addiction (Rosenberg et al., 2014), hypersexuality (Elrafei & Jamali, 2022), and compulsive sexual behaviour (Derbyshire & Grant, 2015). Although these labels originate from different theoretical perspectives, they all refer to persistent and repetitive patterns of sexual impulses and behaviours that the individual finds difficult to control, leading to distress and significant impairment in daily functioning (see Pistre et al., 2023; Sahithya & Kashyap, 2022 for reviews). Among the first to introduce the term sex addiction was Orford (1978), who conceptualised it as a behavioural disorder characterised by compulsive sexual activity pursued despite negative consequences. Since then, interest in this phenomenon has increased, and growing efforts have been made to define its clinical boundaries and underlying psychological mechanisms. A relevant step in this direction occurred during the development of the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, where the condition referred to as hypersexual disorder was proposed for inclusion. This construct described a pattern involving repetitive intrusive sexual fantasies and thoughts, excessive sexual behaviours, and an inability to control one’s sexual activity, resulting in psychological distress and impairment in relational and social life. Despite the scientific debate it generated, the proposal was not accepted, and the disorder was ultimately excluded from the DSM-5 (Kafka, 2010; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). On the other hand, the World Health Organization took a more decisive position. In the latest revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), compulsive sexual behaviour disorder (CSBD) was formally included and categorised as an impulse control disorder (World Health Organization, 2022). According to the ICD-11, CSBD is defined as a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges, resulting in repetitive sexual behaviour over an extended period of time, typically six months or more. The behaviour must lead to marked distress or significant impairment in personal, social, educational, or occupational functioning, and individuals must have made repeated unsuccessful efforts to reduce or control these behaviours. Moreover, the diagnosis cannot be better explained by another mental disorder, substance use, or simply by moral or cultural disapproval of sexual impulses or behaviours.

Within the present study, the term sex addiction was used to remain consistent with a large portion of the empirical literature and with the assessment tools commonly employed in this field (e.g., Soraci et al., 2023). The prevalence of these behaviours tends to be higher during late adolescence and early adulthood (Kafka, 2010), and it has been estimated that up to 25% of individuals seeking psychological help for sexual disorders present behavioural patterns consistent with sex addiction (Levine, 2010). Sex addiction is frequently interpreted as a maladaptive coping mechanism aimed at managing or avoiding painful emotional states, such as shame, loneliness, or unresolved trauma (Carnes, 2001; Woody, 2011). Over time, the compulsive nature of the behaviour reinforces emotional avoidance and contributes to a cycle of psychological distress and interpersonal difficulties. A deeper understanding of the psychological antecedents of this condition is therefore essential for informing prevention strategies and the development of targeted clinical interventions.

Some studies have shown relationships between sexual addiction and emotional dysregulation, anxiety and depression (Hegbe et al., 2022). Sex addiction also could have an impact on the relationship with the partner (Weil, 2018). Given the important implications for mental and relational health, there is a need to understand the antecedents of this condition to improve clinical interventions.

Early works on the topic underline the relevance of alexithymia associated with sexual addiction (Reid et al., 2008), and more recent works also propose the presence of dissociation as a coping mechanism to face early trauma in sexual addictive behaviours (Craparo & Gori, 2015).

ALEXITHYMIA AND SEX ADDICTION

The term alexithymia was introduced by Sifneos (1973) to describe a deficit in the cognitive processing of emotions. Individuals with alexithymia typically show difficulties in identifying and describing their feelings, distinguishing emotional states, and regulating affective responses. They also tend to adopt an externally oriented cognitive style, focusing on concrete, practical details rather than inner emotional experiences (Porcelli et al., 2004).

Recent studies have consistently demonstrated a robust association between alexithymia and problematic or compulsive sexual behaviours, including sex addiction (Gori & Topino, 2024a; Lew-Starowicz et al., 2020; Madioni & Mammana, 2001; Reid et al., 2008; Wise et al., 2002). This association has been interpreted as the result of a maladaptive strategy to manage unresolved emotional distress or trauma-related experiences (Reid et al., 2008), whereby compulsive sexual activity may function as a form of emotional avoidance or affect regulation.

Furthermore, alexithymia has been identified as a transdiagnostic risk factor across multiple forms of behavioural and substance-related addictions (Morie et al., 2016; Speranza et al., 2004), including Internet addiction (Mahapatra & Sharma, 2018), gambling disorder (Gori et al., 2022), and gaming disorder (Liu et al., 2024). In this context, difficulties in emotional awareness and expression may impair an individual’s capacity to use adaptive coping mechanisms, increasing vulnerability to compulsive behaviours such as those observed in problematic sexual behaviours.

THE MEDIATING ROLE OF DISSOCIATION

A growing body of research suggests that the association between alexithymia and addictive behaviours may be partially explained by dissociative processes (Renner et al., 2025), which function as maladaptive strategies for affect regulation in individuals exposed to early trauma or emotional dysregulation (Craparo, 2011; Craparo et al., 2014; Topino et al., 2021). Dissociation, broadly defined as a disruption in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception, may enable individuals to distance themselves from painful internal states that they are otherwise unable to process or express (see Cavicchioli et al., 2021 for a meta-analysis).

Sexual activity, in particular, has been described as a mood-altering behaviour that can facilitate dissociation from unpleasant emotions such as shame, anxiety, or feelings of inadequacy (Quayle et al., 2006). This mechanism may occur on a continuum, from subclinical forms (e.g., brief detachment or emotional numbing; Reid et al., 2008) to more severe dissociative phenomena observed in clinical populations (Griffin-Shelley et al., 1995). Recent studies have emphasised that dissociation may play a mediating role between emotional dysregulation (such as alexithymia) and compulsive behaviours, including sex addiction (Cavicchioli et al., 2021; Gori et al., 2023; Testa et al., 2024). In this view, dissociation may serve as a mechanism of avoidance, allowing individuals with alexithymic traits to escape from overwhelming affective experiences by engaging in compulsive sexual activity, which in turn reinforces both the behaviour and the underlying psychological vulnerability.

GENDER AND SEX ADDICTION

Most studies on compulsive sexual behaviour have historically focused on male samples, limiting the generalizability of findings across genders (Karila et al., 2014). Previous findings reported that the majority of individuals seeking treatment for compulsive sexual behaviour were male, with females comprising only 8% to 40% of clinical samples (see Kaplan & Krueger, 2010 for a review). Although early research suggested a predominance of males among individuals meeting criteria for sex addiction, more recent evidence highlights the importance of considering gender differences in both prevalence and clinical presentation (Bőthe et al., 2023). Shimoni et al. (2018) further observed that men and women differed significantly in the manifestation of problematic sexual behaviours. Women appear significantly less likely to seek treatment, possibly due to greater internalised stigma, feelings of shame, or differences in symptom expression (Dhuffar & Griffiths, 2016). Despite recent progress, the literature remains disproportionately focused on male samples. In this regard, Kowalewska et al. (2020), in their systematic review, highlight substantial gaps in our understanding of women with compulsive sexual behaviour, pointing to methodological limitations and emphasising the need for more inclusive research involving female clinical populations and diverse gender identities.

THE PRESENT RESEARCH

Given the aforementioned empirical framework, the general objective of this research is to elucidate the relationship between factors influencing sex addiction, with a specific focus on alexithymia and dissociation, also including their subdimensions. The specific aims were as follows:

investigate the differences in the levels of dissociation and sex addiction based on the levels of alexithymia profiles, to provide a better understanding of the characteristics related to this phenomenon;

explore the associations between alexithymia subdimensions (difficulty identifying feelings, difficulty describing feelings, and externally oriented thinking) and sex addiction;

analyse the associations between alexithymia and dissociation subdimensions in contributing to sex addiction.

Given the existing scientific literature (e.g., Gori et al., 2023), we expected to find significantly higher levels of dissociation and sex addiction in profiles with higher levels of alexithymia (H1). Then, considering only the alexithymia subdimensions showing a significant total effect in their relationship with sex addiction, a path analysis modelling will implemented, hypothesizing that: the alexithymia subdimensions would be significantly and positively related to the dissociation subdimensions (H2); the dissociation subdimensions would be significantly and positively associated with sex addiction (H3); the dissociation subdimensions would be significant mediators in the relationship between the alexithymia subdimensions and sex addiction (H4).

Finally, since previous studies have shown gender differences in sex addiction (Shimoni et al., 2018), this factor was controlled as a covariate to test the solidity of the interactions hypothesized in the model.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

This research adopted a cross-sectional design and involved a sample of 326 participants (83% females, 17% males; Mage = 28.29, SD = 11.76). As shown in Table 1, the majority were single (76%) and reported having a high school diploma (45%) or a university degree (33%). Regarding their occupation, a significant portion identified as students (46%), and as employed (25%). They were recruited online through snowball sampling, and completed the survey online, on the Google Forms platform. Each participant was informed about the study’s general aims and provided electronic informed consent before starting the survey. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the institution of one of the authors.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 326)

MEASURES

Twenty‐Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS‐20). The 20‐Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS‐20; Bagby et al., 1994a, 1994b; Italian version: Bressi et al., 1996) is a 20‐item self‐report scale for assessing the levels of alexithymia. Items are on a five‐point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and may be grouped in both a total score and three subscales (1 – difficulty identifying feelings; 2 – difficulty describing feelings; 3 – externally oriented thinking). The total score of the TAS-20 can be used to categorize participants into three groups: a cut-off above a value of 61 indicates an alexithymic condition; scores equal to or less than 51 indicate no alexithymia; scores between 52 and 60 suggest a possibility of alexithymia. The Italian version was used in this research and showed good internal consistency in the present sample (total score, α = .86; difficulty identifying feelings, α = .87; difficulty describing feelings, α = .80; externally oriented thinking, α = .60).

Dissociative Experience Scale‐II (DES‐II). The Dissociative Experiences Scale‐II (DES‐II; Carlson & Putnam, 1993; Italian version: Schimmenti, 2016) is a 28‐item self‐report scale for assessing the levels of dissociative experiences. Items are on an 11‐point scale from 0% (never) to 100% (always), and may be grouped in both a total score and three subscales: dissociative amnesia, absorption, and depersonalization-derealization. Higher scores indicate greater levels of psychological dissociation. The Italian version was used in this research and showed good internal consistency in the present sample (total score, α = .95; dissociative amnesia, α = .83; absorption, α = .85; depersonalization‐derealization, α = .89).

Bergen-Yale Sex Addiction Scale (BYSAS). The Bergen-Yale Sex Addiction Scale (BYSAS; Andreassen et al., 2018; Italian version: Soraci et al., 2023) is a 6-item self‐report scale for assessing the levels of problematic sex behaviour, based on the components model of addiction (Griffiths, 2005). Items are on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Higher scores indicate greater levels of problematic sex behaviour. The Italian version was used in this research and showed good internal consistency in the present sample (α = .80).

DATA ANALYSIS

The collected data were analysed using the SPSS (version 27.0) and AMOS (version 24.0) software for Windows. Descriptive statistics, ANOVAs, and regression analysis were performed as preliminary analyses. Specifically, ANOVAs were implemented to explore differences in the levels of dissociation and sex addiction (dependent variables) based on the levels of alexithymia, by including the alexithymic profiles (Non-alexithymia, Possible alexithymia, Alexithymia) as independent variable. The Scheffé test was used as post‐hoc analysis to improve the interpretation of the differences. Multiple regression analysis was performed to explore the total effects in the relationship between alexithymia subdimensions and sex addiction, controlling for the effect of gender (men coded as 0 and women coded as 1). Then, only the subdimensions that demonstrated a significant total effect were included in the path analysis model, where the parallel mediation of the dissociation subdimension was explored, controlling for the effect of gender as a covariate. The statistical goodness of fit of the model was assessed based on the following indices: the chi-square (χ2) of the model, suggesting a good fit when p > .05 (Hooper et al., 2008); the goodness of fit index (GFI), normed-fit index (NFI), and comparative fit index (CFI), suggesting a good fit when the values are above 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2015); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), suggesting a reasonable fit when the values are below 0.08 (Hooper et al., 2008; Marsh et al., 2004). Finally, the statistical stability of the model was investigated by analysing the significance of total, direct and indirect paths performing the bootstrap technique (5000 bootstrapped samples with 90% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals): the significance of the effects occurred when the bootstrap confidence intervals (from lower limit confidence interval [Boot LLCI] to upper limit confidence interval [Boot ULCI]) did not encompass zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Table 2

Means, standard deviations and comparisons of the levels of dissociation and sex addiction based on alexithymie profiles

RESULTS

PRELIMINARY ANALYSES

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. Regarding alexithymia profiles, the majority of participants exhibit scores characteristic of “Non-alexithymia” subjects (52%), 31% fall into the group of “Possible alexithymia”, 17% within the “Alexithymia” group (see Table 1).

The results of the ANOVAs highlighted statistically significant differences in the levels of dissociation (F2,323 = 37.77, p < .001) and sex addiction (F2,323 = 31.45, p < .001) based on the levels of alexithymia. Specifically, as levels of alexithymia increased, subjects exhibited higher levels of dissociation and sex addiction (see Table 2).

Multiple regression analysis showed a significant and positive total effect in the association of difficulty in describing feelings (β = .15, p = .030) and difficulty in identifying feelings (β = .31, p < .001) with sex addiction. In contrast, the relationship between externally oriented thinking and sex addiction was non-significant (p = .618). Finally, the effect of gender as a covariate was controlled in these associations (β = –.23, p < .001)

PATH ANALYSIS MEDIATION MODEL

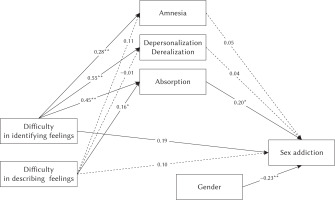

Based on preliminary analyses, the association between difficulty in describing/identifying feelings and sex addiction was investigated, exploring the mediation of the dissociation subdimension (dissociative amnesia, absorption, depersonalization‐derealization) and controlling for the effect of gender as a covariate. The emerging parallel mediation model showed a good fit to the data: χ2 = 31.22 (5), p < .001; GFI = .975; NFI = .967; CFI = .972; RMSEA = .061 (see Figure 1).

Specifically, difficulty in identifying feelings was significantly and positively associated with dissociative amnesia (β = .28, p < .001), depersonalization‐derealization (β = .55, p < .001), and absorption (β = .45, p < .001). Difficulty in describing feelings was significantly and positively associated with absorption (β = .16, p = .008), but not with dissociative amnesia (p = .113) and depersonalization‐derealization (p = .887). Furthermore, among the dissociation subdimension, only absorption was significantly and positively associated with sex addiction (β = .20, p = .006). With regards to the covariate, being male was associated with higher levels of sex addiction (β = –.23, p < .001). When all the variables were included in the model, absorption partially mediated the effect of difficulty in identifying feelings on sex addiction (β = .19, p = .017), and totally mediated the effect of difficulty in describing feelings on sex addiction (β = .10, p = .106). Finally, the bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (5000 bootstrapped samples) confirmed the statistical stability of the path analysis model (see Table 3).

Figure 1

The relationship between difficulty identifying/describing feelings and sex addiction, with the mediation of the dissociation components and controlling for gender

Note. Standardized coefficients. Continuous lines represent statistically significant paths (p < .05); dashed lines represent non-significant paths; *value significant at the .01 level; **value significant at the .001 level.

Table 3

Coefficients of the path analysis

DISCUSSION

With the codification of the compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) in the ICD-11 (WHO, 2022), the focus on the topic and its clinical implications has increased (Pocknell & King, 2019). Furthermore, scientific evidence has highlighted a non-negligible prevalence of such problematic sexual behaviours (Levine, 2010; Sahithya et al., 2021). Since a better understanding of the path that leads to the development of the pathology may be useful to improve clinical interventions (Craparo, 2014), this research aimed at investigating the role of alexithymia and dissociation in relation to sex addiction.

The results showed that alexithymic profiles reported higher levels of dissociation and sex addiction (H1). This is in agreement with the partial evidence of previous studies (Gori et al., 2022, 2023; Gori & Topino, 2024a), confirming and therefore extending the evidence about the role of alexithymia and dissociation for both substance use disorders and compulsive behaviours, including sex addiction.

The path analysis further expanded these results by exploring the role of the subdimensions of the variables examined. Concerning the subdimensions of alexithymia, only difficulty in describing feelings and difficulty in identifying feelings showed a significant relationship with sex addiction, while the association with externally oriented thinking was non-significant. Furthermore, difficulty identifying feelings shows a robust relationship with all dimensions of dissociation, while difficulty describing feelings is implicated only in absorption (H2), indicating less impact on amnesia and depersonalization/derealization than reported in the literature that tested the general relationship (see Reyno et al., 2020 for a review). Among the subdimensions of dissociation, only absorption seems solidly implicated in the formation of sex addiction (H3). This result is consistent with previous theory on dissociation as a flight from unlikely emotion: absorption would therefore place these sexual behaviours as a coping strategy to manage these emotions (Craparo, 2014). Consistently, absorption appears to be the most robust mediator between alexithymia and sex addiction, while depersonalization, derealization and amnesia do not show robust effects in the model (H4). These results are consistent with the most recent works that have explored this mediation effect on other behavioural addictions (Gori & Topino, 2024b), explaining that subjects take refuge in a pleasant altered state of consciousness, which however increases the risk of developing addiction. This evidence may be useful from a clinical point of view, as by placing emphasis on absorption, it indicates the need to consider this element as crucial in the planning of therapeutic intervention for sex addiction. Finally, the role of gender as a covariate was explored, and the results showed that being male was positively associated with higher levels of sex addiction. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting higher rates of problematic sexual behaviour among men (Shimoni et al., 2018). However, this does not necessarily imply that women experience compulsive sexual behaviour to a lesser extent. Rather, emerging evidence suggests that gender differences may reflect variations in behavioural expression, symptom reporting, and help-seeking patterns, rather than true prevalence gaps (Dhuffar & Griffiths, 2016). Specifically, women with compulsive sexual behaviour may exhibit more internalised forms of distress and are less likely to seek treatment, often due to feelings of shame, self-stigma, or fear of social judgement (Kowalewska et al., 2020). Furthermore, gender norms and stereotypes may contribute to under-recognition or underreporting of the disorder among women (Kürbitz & Briken, 2021; Petersen & Hyde, 2011). Therefore, while our findings support the relevance of gender in the model, they also highlight the importance of adopting gender-sensitive approaches in both research and clinical settings, to ensure that the distinct experiences of female individuals with sex addiction are adequately captured and addressed.

The study also presents some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits the possibility of establishing causal inference between the variables. To overcome this weakness, future studies could adopt a longitudinal design monitoring the variation in levels of sex addiction over time. Furthermore, the variables in our sample were assessed through the use of self-report tools, which allow the standardized measurement of the variables with excellent cost-time efficiency, but are sensitive to response biases, self-selection bias and social desirability. Future research could focus on the detection of directly observable behavioural variables or mix both methodologies.

CONCLUSIONS

This study contributes to the scientific literature about behavioural addictions by extending the evidence on the mediating role of dissociation in the relationship between alexithymia and sex addiction. The findings may improve the understanding of the antecedents of sex addiction, and this may provide insight for effective therapeutic interventions or prevention programmes. Specifically, the identification of absorption as the key mediating dissociative process suggests that treatment could benefit from targeting this factor. Interventions that focus on promoting mindful emotional awareness may help individuals develop healthier strategies for managing distressing emotions. This is particularly relevant for alexithymic individuals, who may struggle to access, label, or express their emotional experiences and are more prone to dissociative states. In addition, clinicians should assess dissociative features early in treatment, as they may interfere with emotional processing and therapeutic engagement. Psychoeducation on dissociation, emotional literacy training, and grounding techniques could be integrated into clinical work to help reduce the reliance on compulsive sexual behaviours as a dysfunctional form of emotional regulation. Finally, considering the gender-based differences observed in the sample, future interventions should also be sensitive to gender-specific manifestations of compulsive sexual behaviour and consider how shame, stigma, or social scripts may shape symptom expression differently in men and women. From a preventive perspective, these findings highlight the importance of early interventions focused on emotional competence and trauma-informed education, particularly in adolescence and early adulthood, where the risk of developing problematic sexual behaviours may be higher. Promoting emotional self-regulation skills and awareness of dissociative experiences in educational or community settings could reduce the likelihood of maladaptive behavioural responses becoming chronic and compulsive. Taken together, these findings offer a framework that can guide therapists in tailoring both prevention and intervention strategies, thereby enhancing early identification efforts and improving treatment outcomes.