BACKGROUND

College students experience numerous upheavals and instability while structuring their lives across various aspects such as intrapersonal relationships, academic activities, career, interpersonal relations, finances, and romance (Arnett, 2000; Levinson, 1978). Moreover, in the transition from adolescence to adulthood, students are often expected to take on adult responsibilities without yet possessing the necessary skills and cognitive maturity of adulthood (Pedrelli et al., 2015). The complexity of these challenges, divided into academic and non-academic stressors, makes the college phase immensely critical and stressful, rendering students highly vulnerable to mental health issues (Arnett, 2000; Caldarelli et al., 2024; Campbell et al., 2022; Emmerton et al., 2024; González-Martín et al., 2023).

Several studies have revealed that the prevalence of mental health issues among students worldwide has been rising at an alarming rate (Caldarelli et al., 2024; Emmerton et al., 2024; Malebari et al., 2024), with psychological distress, anxiety, depression, adjustment disorders, eating disorders, sleep problems, and substance abuse being common and widespread among this cohort (Balon et al., 2015; Campbell et al., 2022; Kirdchok et al., 2022; Limone & Toto, 2022; Pedrelli et al., 2015). Self-harm and suicide rates have also increased among college students (Campbell et al., 2022; Clements et al., 2023; Klonoff-Cohen et al., 2024; Sivertsen et al., 2019).

However, when individuals possess positive qualities within themselves, they tend to be more capable of overcoming stress and adverse events, managing stress effectively, maintaining health, and demonstrating improved mental well-being (Duan, 2016; Duan et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). One such personal quality is self-compassion (Zhang et al., 2016), which serves as a protective factor for emotional responses to stress (Bluth & Neff, 2018; Cowand et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2016). Self-compassion is a dispositional self-attitude that reflects openness to one’s own suffering, experiencing care, kindness, and tolerance towards oneself, holding a non-judgemental understanding of personal imperfection and failure, and recognizing hard times as part of the common human experience (Gutiérrez-Hernández et al., 2023; Mantzios & Egan, 2018; Neff, 2003a). Self-compassion also encompasses acts of soothing and reassuring oneself instead of engaging in self-criticism during difficult situations (Gilbert et al., 2004), which can protect individuals from the negative effects of self-judgment, isolation, and rumination (Cowand et al., 2024). Individuals with high self-compassion are less likely to self-blame, more likely to evaluate and reflect on their mistakes and alter unproductive behaviours, and able to face new challenges (Hidayati, 2015).

Neff (2003a) conceptualized self-compassion into three main components. The first is self-kindness, which refers to treating oneself kindly and with compassion during suffering or difficult times. According to Allen and Leary (2010), this can be manifested through tangible actions such as taking time to calm oneself, or mental acts such as positive self-talk, encouragement, and forgiveness. The second is common humanity, which refers to recognizing that one’s painful experiences are part of the broader human experience. When individuals realize they are not alone in feeling pain from failure, loss, or rejection, their sense of isolation tends to decrease, and their adaptive coping improves (Neff, 2003a). Finally, mindfulness, which Neff (2003b) identified as the core component of self-compassion, refers to the capacity to hold one’s emotional experiences in balanced awareness and respond nonjudgmentally (Bluth & Blanton, 2014), as opposed to avoiding or being overwhelmed by those emotions (Lathren et al., 2021). Individuals with low self-compassion tend to focus on their difficulties and become immersed in negative emotions. However, those who face adverse situations mindfully are more likely to overcome them successfully (Allen & Leary, 2010).

Previous studies have highlighted the essential role of self-compassion among youth. Youth with high self-compassion tend to treat themselves with kindness and care when facing negative experiences, report lower levels of neuroticism and depression, and show higher life satisfaction, social connectedness, and subjective well-being. Conversely, low self-compassion is associated with maladaptive behaviours (Allen & Leary, 2010; Tran et al., 2022). A meta-analysis by Suh and Jeong (2021) indicated that self-compassion is significantly and negatively associated with suicidal thoughts and non-suicidal self-injury. Furthermore, higher levels of self-compassion are linked to fewer negative emotions, more positive emotions, lower anxiety, and reduced daily stress reactivity (Tran et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2016). Self-compassion enhances behavioural motivation and self-regulation during difficult times (Neff, 2003a), and may protect individuals from distress and mood disorders (Cowand et al., 2024). In college settings, self-compassion mitigates the negative effects of academic stress on negative affect and depression (Zhang et al., 2016) and positively correlates with happiness, spirituality, optimism, emotional intelligence, coping abilities, self-improvement motivation, perceived competence, and the use of cognitive reappraisal (Baer et al., 2012; Bluth & Blanton, 2014; Naidoo & Oosthuizen, 2024), which serve as protective factors for students’ adjustment in university life (Naidoo & Oosthuizen, 2024).

According to Neff (2003b), one of the components of self-compassion is mindfulness, which is considered to be the core of self-compassion itself. Mindfulness is defined as a mental state that enables individuals to concentrate on the present moment, their surrounding environment, and current activities without being distracted by past or future events (Baer et al., 2006). Mindfulness is both a psychological process and a coping skill that involves an external, internal, and non-judgemental reaction to awareness based on attention and vigilance (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Taren et al., 2013). Mindfulness serves to enhance focus, awareness, and self-confidence; reduce distraction, anxiety, tension, and depression; foster self-acceptance, a sense of control, and environmental management; enrich the sense of life’s meaning; and provide insight into thinking patterns, emotions, social interactions, and appropriate responses when facing various situations (Alomari, 2023). In turn, mindfulness yields self-regulation, leads to increased productivity and individual performance (Alomari, 2023; Shapiro et al., 2008), contributes to improved health outcomes, promotes resilience and well-being, and helps individuals manage unpleasant emotions or feelings (Ahmadi et al., 2014; González-Martín et al., 2023). Additionally, in college students, mindfulness can support personal growth in higher education (González-Martín et al., 2023).

Studies have shown a significant positive correlation between mindfulness and self-compassion (Bluth & Blanton, 2014; Makadi & Koszycki, 2020; Sedighimornani et al., 2019). Summarizing the previous literature, Bluth and Blanton (2014) found that self-compassion plays a role as an influential mediator in the relationship between mindfulness and well-being, highlighting a pathway from mindfulness to self-compassion that indicates the predictive effect of mindfulness on enhancing self-compassion. Youth with higher levels of mindfulness tend to be more open and responsive to negative experiences instead of avoiding, suppressing, rejecting, or judging them, thereby reducing vulnerability to depression and suicidal ideation (Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Su et al., 2022), since being mindful is associated with awareness, openness, acceptance, non-judgment, cordiality, kindness, and compassion (Baer et al., 2019). A mindful condition – which embodies being more attentive, more aware, and more accepting and acknowledging of current thoughts or feelings – allows individuals to treat themselves more kindly and less critically (Bluth & Blanton, 2014). Thus, it is hypothesized that mindfulness predicts self-compassion.

Furthermore, most studies agree that family factors constitute a fundamental system with a direct and enduring impact on individual development (Pomerantz et al., 2008), which, when positive, can act as a protective factor for students’ mental health (Emmerton et al., 2024; Novak et al., 2021). A family-related factor that plays a pivotal role in coping with and overcoming stressors – and is closely associated with mental health (Desrianty et al., 2021; Qin et al., 2023), resilience (Zarei & Fooladvand, 2022), and life satisfaction among students (Grevenstein et al., 2019; Wenzel et al., 2020) – is family functioning. Family functioning refers to the extent to which or how effectively a family as a unit fulfils essential roles, communicates, has emotional connection, and copes with adverse situations (Epstein et al., 1983; Olson, 2000). Furthermore, family functioning represents the mental health condition of a family, encompassing each member’s ability to understand roles, rights, and obligations while engaging in familial dynamic patterns physically, psychologically, and socially (Dai & Wang, 2015). Optimal family functioning bolsters the development of both physical and mental health among family members, including children (Beavers & Hampson, 2000; Miller et al., 2000; Olson, 2000; Skinner et al., 2002).

A growing body of literature has documented the significant impact of family functioning on college students (Qian et al., 2022). For instance, students from well-functioning families – characterized by open communication and low conflict – are more likely to develop more adaptive coping strategies (Huang et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2021), as well as to optimize their problem-solving abilities, emotional and behavioural regulation, and interpersonal communication (Szcześniak & Tułecka, 2020). In contrast, poor family functioning – marked by high conflict and low support – has been consistently associated with a range of psychological difficulties, including anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances (Pan et al., 2021), as well as diminished academic performance and learning outcomes (Deng et al., 2022).

Furthermore, individuals raised in warm, cohesive, and supportive family environments are more capable of embracing personal imperfections with empathy – an essential aspect of self-compassion (Neff & McGehee, 2010). Consequently, they are more likely to report higher levels of self-compassion (Berryhill et al., 2018; Lathren et al., 2021). Conversely, those who experienced coldness, neglect, rejection, or even abuse from their parents or caregivers during childhood often report lower self-compassion (Lathren et al., 2021). A recent longitudinal study by Fan and Yang (2025) also demonstrated a reciprocal influence between family functioning and self-compassion over time, highlighting the dynamic interplay between relational experiences and the long-term development of intrapersonal capacities.

Beyond its role in shaping intrapersonal traits such as self-compassion, family functioning also contributes to the development of mindfulness dispositions in adolescents and emerging adults. Several empirical studies have found that positive parenting practices and supportive family relationships are significantly associated with higher levels of mindfulness (Nieto et al., 2023; Su et al., 2022). Warm, responsive, and supportive parent-child interactions not only strengthen secure attachment, but also create psychological space for youth to develop a full and open awareness of their internal experiences (Caldwell & Shaver, 2015). Moreover, longitudinal evidence from Su et al. (2022) indicates that positive parenting is not only related to increased mindfulness, but also exerts a protective effect against maladaptive psychological symptoms through the mediation of mindfulness. These findings suggest that mindfulness is more likely to flourish within family environments that provide structure, emotional support, and adaptive interaction models. Accordingly, it can be posited that family functioning may influence individual mindfulness levels.

Although studies have identified positive associations between family functioning and mindfulness, as well as between mindfulness and self-compassion, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet examined the mediating role of mindfulness in the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion. Based on prior findings that underline the contribution of family functioning to the development of mindfulness (Su et al., 2022), and the consistent evidence indicating mindfulness as a robust predictor of self-compassion (Baer et al., 2019; Bluth & Blanton, 2014; Su et al., 2022), a conceptual foundation emerges for a potential indirect pathway in which mindfulness mediates this relationship. Thus, it is plausible to assume that mindfulness serves as a psychological mechanism bridging the influence of family context and the development of valuable intrapersonal qualities such as self-compassion.

To conceptually frame these associations, this study draws upon several psychological theories. First, the family systems theory (Bowen, 1974) posits that family functions play a crucial role in shaping mindfulness as individuals’ self-regulation and attentional patterns through daily interactions and emotional coping strategies such as self-compassion. Within this framework, family functioning is not merely a background variable, but a dynamic system that influences the development of individuals’ internal qualities such as mindfulness and self-compassion. Second, the relational developmental systems (RDS) metamodel (Lerner et al., 2015) highlights the dynamics that regulate exchanges between individual structure or function (e.g., personality, cognitive, intelligence) and their proximal and distal ecological context (e.g., family, culture, history), emphasizing how personal competencies such as mindfulness and self-compassion develop through interactions with the environment. Together, these theories support the proposed mediational pathway and provide a foundation for understanding how intrapersonal traits may emerge from familial dynamics.

Most research on family-related constructs such as family functioning and their relation to mindfulness or self-compassion has been predominantly conducted among parents (e.g. Benn et al., 2012; Gouveia et al., 2016; Moreira et al., 2016; Psychogiou et al., 2016) or adolescent samples from secondary schools (e.g. Fan & Yang, 2025; Watkins et al., 2022). Moreover, while several studies have separately examined these three variables in college populations – for instance, Berryhill et al. (2018) investigated the link between family functioning and self-compassion among 500 college students aged 18-19, and Desai et al. (2025) focused on young adults aged 20-35, including college-aged individuals – none has tested all three variables within a single pathway model. Consequently, the direct and indirect effects of these interrelated variables among college students remain underexplored, leaving a notable gap in developmental and clinical psychology literature. Considering the importance of understanding the relational and internal pathways that contribute to positive psychological development, investigating this triadic mechanism in college populations represents a crucial step toward enriching the current theoretical and empirical landscape. Hence, this study aims to examine the relationship between mindfulness, family functioning, and self-compassion in college students. Based on the literature review above, the hypotheses proposed are:

H1: Family functioning predicts mindfulness among college students.

H2: Mindfulness predicts self-compassion among college students.

H3: Family functioning predicts self-compassion among college students.

H4: Mindfulness mediates the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion among college students.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

In this study, we conducted an a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 to determine the minimum required sample size, in which effect size estimation served as one of the key parameters. A medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) was selected as a conservative approach, given the absence of prior empirical studies that were contextually comparable – specifically those examining the relationships between the key variables among college students in a collectivist cultural context such as Indonesia. This approach is commonly adopted in psychological research to avoid overly optimistic estimations, as Cohen (1992) recommended that a medium effect size typically approximates the average effect observed across various fields. Based on the G*Power 3.1 analysis, the minimum sample size required for this study was 107 participants. In addition, inclusion criteria were established as follows: active university students in Indonesia (not on academic leave or disengaged), not undergoing psychiatric treatment (to eliminate pharmacological influences), and willing to participate voluntarily. Individuals who did not meet these criteria were excluded. A total of 287 college students aged 17-29 years from 15 universities in Indonesia met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final sample – indicating that the achieved sample size was adequate for the study’s analytical requirements.

PROCEDURE

This study was conducted with ethical approval from Diponegoro University (number: 286/EA/KEPK-FKM/2021). This study employed a cross-sectional correlational approach to explore the direct effects among mindfulness, self-compassion, and family functioning, as well as the indirect effect of the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion while mediated by mindfulness. Data were collected using convenience sampling based on participants’ availability and willingness to participate (Golzar et al., 2022) through an online survey. A set of questionnaires was distributed via Google Forms to accessible universities across Indonesia, and institutional representatives subsequently shared the link with their students. Respondents were asked to provide informed consent prior to participation, which included detailed information about the study and ethical considerations. Only participants who met the inclusion criteria – being actively enrolled university students in Indonesia (not on academic leave or disengaged), not undergoing psychiatric treatment (to minimize the influence of medication), and voluntarily agreeing to participate – were included in the analysis.

Additionally, it is important to acknowledge potential issues associated with online surveys. Despite their increased accessibility, reach, and widespread use in recent years, online surveys remain vulnerable to various errors, particularly those related to the invalidity of participant responses (Curran, 2016). Johnson (2005) identified three main sources of invalid data: incompetence or linguistic misunderstanding, misrepresentation, and careless or inattentive responding. To anticipate and minimize the risk of invalid responses, several procedures were implemented to maintain the quality and integrity of the collected data. First, clear explanations and instructions were provided for each instrument, including descriptions for each response option (e.g., Likert scale points accompanied by descriptive labels, following the original instruments), to prevent respondent misinterpretation. Second, we ensured that all items included in the Google Form were presented in well-structured, grammatically correct, and unambiguous Indonesian language. Third, the layout of the Google Form was carefully designed for effectiveness, such as by separating the pages for informed consent, demographic information, and each scale, to avoid overwhelming respondents with an excessively long questionnaire at the beginning. In relation to the latter two points, we also conducted a full preview and trial completion of the Google Form prior to distribution to evaluate its usability and clarity. Finally, a thorough screening of the dataset was conducted prior to analysis to ensure the absence of duplicate entries.

MEASURES

Three instruments were used in this study: the Brief Family Assessment Measure III to evaluate family functioning; the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) to assess mindfulness; and the Self-Compassion Scale to measure levels of self-compassion.

Family functioning. The Brief Family Assessment Measure III (FAM-III), developed by Skinner et al. (2002), evaluates overall family functioning using three subscales: the Dyadic Scale (5 items; α = .88), General Scale (6 items; α = .79), and the Self-Report Scale (7 items; α = .74). Each subscale uses a four-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly agree) to 3 (strongly disagree). The item samples of this scale are: “In the family, we are free to express our thoughts and opinions”, “I know I can count on other members of my family”, and “We take the time to truly listen to one another”. FAM-III provides a scoring procedure that allows raw scores to be converted into T-scores for clinical interpretation purposes (Skinner et al., 2002). However, in the present study, raw scores were used to examine the relationships among variables, as T-scores are primarily intended for clinical interpretation and are not suitable for inferential statistical analyses within the context of research.

Mindfulness. The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) consists of 16 items developed by Brown and Ryan (2003) and adapted by Fourianalistyawati et al. (2018), with a Cronbach’s α of .83, indicating good psychometric properties. The item samples of this scale are: “I sometimes experience certain emotions without noticing them until later”, “I find it difficult to stay focused on what is happening in the present”, and “I perform tasks automatically, without being fully aware of what I’m doing”. The MAAS uses a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never), with higher scores indicating greater levels of mindfulness.

Self-compassion. The Self-Compassion Scale, developed by Neff (2003b) and adapted by Sugianto et al. (2020), was used to measure self-compassion. The item samples of the Self-Compassion Scale are: “I make an effort to love myself when I feel emotionally hurt”, “When I experience something difficult, I remind myself that challenges are a part of every person’s life”, and “During difficult times, I place the blame on myself”. This 26-item scale has four response options ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree), with higher scores reflecting greater self-compassion. The Cronbach’s α was .87, demonstrating strong reliability.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data analysis in this study was conducted in several stages. First, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the key variables (family functioning, mindfulness, and self-compassion) as well as demographic characteristics (age, gender, educational background, parental marital status, living arrangement, and academic discipline – categorized into STEM and socio-humanities fields). For continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation were reported, while frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. Second, prior to the main analysis, bivariate analyses using Pearson correlation and regression tests were conducted to examine the interrelationship between the key variables. These preliminary analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 27. Subsequently, mediation analysis was conducted using Jamovi version 2.3.26 with a bootstrap sample of 5,000 to generalize population estimates. The significance threshold across all analyses was set at α = .05. Nonetheless, p-values are reported as obtained in the analyses and interpreted according to conventional significance levels (p < .05, p < .01, and p < .001).

Table 1

Participants’ demographic characteristics

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the 278 college students who participated in the study, with a mean age of 19.5 years (SD = 2.21). A total of 62.9% of participants identified as female, while 37.1% identified as male. The majority of the participants were undergraduate students (92.5%), with the remaining 7.5% enrolled in master programmes. In terms of academic major, 51.1% of participants were from STEM fields, while 48.9% were from social sciences and humanities disciplines. Regarding parental marital status, participants reported their parents as married (83.5%), divorced (7.9%), and widowed (8.6%). Most participants revealed living with their parents (57.2%), while the rest lived separately (42.8%). Descriptive analysis further indicated that the majority of participants reported moderate levels across the three key variables: family dysfunction (M = 20.4, SD = 11.28), mindfulness (M = 60.3, SD = 13.05), and self-compassion (M = 43.2, SD = 11.29). The categorization of these variables into low, moderate, and high levels was based on the distribution of scores, with the moderate level defined as scores falling within one standard deviation of the mean.

CONFOUNDER ANALYSES

Bivariate statistics. Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the associations between the key variables and demographic factors as potential confounders (age, gender, educational back-ground, academic major, parental marital status, and living arrangement).

As presented in Table 2, the results revealed that three demographic variables were significantly associated with family functioning: age (r = .14, p = .023), academic major (t = 3.31, d = .40, p = .001), and parental marital status (F = 4.16, η² = .03, p = .017). However, none of these variables showed significant associations with mindfulness or self-compassion.

Regression analysis. Table 3 presents the results of the regression analyses examining the relationships among the key variables, in both the baseline model (without covariates) and the adjusted model (controlling for age, academic major, and parental marital status) to determine whether these three demographic variables function as confounders in the associations among the key variables. Regression analyses were conducted only for the pathways involving family functioning, as the three covariates were significantly associated solely with family functioning and not with mindfulness or self-compassion. Therefore, only the direct relationships between family functioning and mindfulness, as well as family functioning and self-compassion, were included in the regression analyses.

Results from the baseline model indicated that family functioning was negatively associated with both mindfulness (β = –.41, p < .001) and self-compassion (β = –.43, p < .001). After controlling for the three covariates in the adjusted model, family functioning remained significantly negatively associated with mindfulness (β = –.43, p < .001) and self-compassion (β = –.43, p < .001). Although age was significantly positively associated with mindfulness (β = .14, p = .024), the effect size was weak and did not alter the significance or direction of the primary relationships. Age was not significantly related to self-compassion (β = .07, p = .258). Additionally, academic major and parental marital status were not significantly related to either outcome variable in both models.

Compared to the baseline model, the β coefficients in the adjusted model demonstrated minimal changes. The ΔR² values showed only slight increases (2.3% in the family functioning and mindfulness pathway; 0.6% in the family functioning and self-compassion pathway). The absence of changes in the significance of the primary associations after controlling for covariates indicates that age, academic major, and parental marital status did not meet the criteria for compelling confounding. Accordingly, these findings suggest that the relationships between family functioning and both mindfulness and self-compassion are relatively stable and are not substantially confounded by these demographic variables. Thus, the three covariates were excluded from subsequent correlation and mediation analyses.

Correlation analysis. Pearson correlation analysis was employed to examine the relationships among family functioning, mindfulness, and self-compassion. The results, shown in Table 4, revealed a significant negative correlation between family functioning and mindfulness (r = –.41, p < .001), suggesting that higher levels of family dysfunction were associated with lower levels of mindfulness. Similarly, family functioning was negatively correlated with self-compassion (r = –.43, p < .001), indicating that greater family dysfunction was related to decreased self-compassion. In contrast, mindfulness was positively correlated with self-compassion (r = .54, p < .001), implying that individuals with higher levels of mindfulness tended to report better self-compassion. Overall, these findings highlight significant interrelationships among the three key variables, providing a fundamental foundation for further mediation analysis.

MEDIATION ANALYSIS

Mediation analysis was performed using Jamovi 2.3.26 with 5,000 bootstrap samples to investigate the mediating role of mindfulness in the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion.

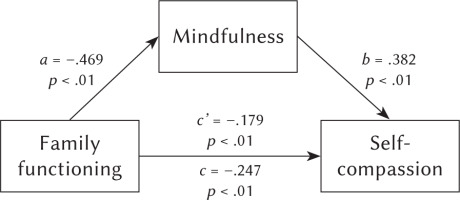

As shown in Table 5, family functioning significantly predicted mindfulness among college students in a negative direction (path a; β = –.47, p < .001, 95% CI [–.608, –.325]), indicating that poorer family functioning was associated with lower levels of mindfulness. This result supports hypothesis 1. Furthermore, mindfulness significantly predicted self-compassion (path b; β = .38, p < .001, 95% CI [.280, .483]), suggesting that increased mindfulness was linked to higher self-compassion, thereby supporting hypothesis 2. Moreover, family functioning was negatively associated with self-compassion (path c; β = –.43, p < .001, 95% CI [–.543, –.301]), demonstrating that greater family dysfunction was related to lower levels of self-compassion, in line with hypothesis 3.

Table 2

Results of bivariate tests of demographic variables with key variables

Table 3

Results of regression test

Table 4

Pearson correlation test result

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-compassion | 20.40 | 11.28 | – | – | – |

| 2. Mindfulness | 60.30 | 13.05 | .54* | – | – |

| 3. Family functioning | 43.20 | 11.29 | –.43* | –.41* | – |

Table 5

Results of the mediation test

The indirect effect (path ab) of family functioning on self-compassion through mindfulness was also significant (β = –.18, p < .001, 95% CI [–.235, –.114]), implying partial mediation, with mindfulness accounting for 42.1% of the total effect. Thus, hypothesis 4 was supported. Meanwhile, the direct effect of family functioning on self-compassion (path c′) remained significant (β = –.25, p < .001, 95% CI [–.363, –.129]), accounting for 57.9% of the total effect. These findings support the proposed theoretical model, in which mindfulness partially mediates the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion (see Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to examine the relationship between family functioning, mindfulness, and self-compassion while highlighting mindfulness as a mediating variable. It is crucial to underscore that the family functioning measure used in this study assessed family dysfunction, such that higher scores reflected greater levels of dysfunction. The findings supported all four hypotheses: Family functioning was significantly negatively associated with both mindfulness and self-compassion among college students. In other words, students who perceived higher family dysfunction tended to report lower levels of mindfulness and self-compassion. Moreover, mindfulness was positively associated with self-compassion, suggesting that increased mindfulness was linked to heightened self-compassion. Importantly, mindfulness was found to partially mediate the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion. These findings lend support to the proposed theoretical model and accentuate the essential role of the relational context, particularly the family system, in cultivating intra-personal capacities among university students.

The observed associations between family dysfunction and lower levels of mindfulness and self-compassion align with a substantial body of literature emphasizing the central role of the family as the primary system that shapes and reflects an individual’s views, attitudes, and values toward oneself and the world (Witchel, 1991). This system exerts a direct and enduring influence on mental health (Chen et al., 2023). While some families recognize the importance of emotional acceptance and the fulfilment of children’s needs, others may neglect or fail to meet these fundamental developmental requirements, delineating dysfunctional family patterns. Dysfunctional families, characterized by persistent conflict, tense relationships, emotional neglect, poor and unempathetic communication, low cohesion, and limited adaptability, can leave emotional wounds that adversely affect a child’s personality, emotional regulation, and physical development (Farmakopoulou et al., 2024; Mphaphuli, 2023). The repercussions of such dysfunction can extend into adulthood, particularly during the transition to higher education. Witchel (1991) observed that many students carry unresolved familial conflicts, painful personal histories, and emotional residue into academic environments, even when physically separated from their families. As a result, students from dysfunctional families are more vulnerable to affective disturbances (Chen et al., 2023), often manifesting as feelings of insecurity, unworthiness, rejection, and emotional neglect (Mphaphuli, 2023).

Beyond the affective domain, family dysfunction also influences cognitive and psychological patterns, particularly the emergence of the inner critic, an internalized voice of self-judgment and blame (Katz & Nelson, 2007; Šoková et al., 2025). Self-criticism, which stands in opposition to self-compassion (Kirschner et al., 2019; Neff, 2003b), emphasizes self-condemnation in response to failure, imperfection, or distress. Individuals who adopt self-critical tendencies often internalize early negative interactions with emotionally distant, controlling, or critical parents or caregivers. As a result, they view themselves as unworthy and develop mistrust toward others (Blatt & Homann, 1992). Katz and Nelson (2007) asserted that perceived parental criticism, rejection, and indifference are strongly associated with elevated self-criticism among both college students and adults.

Conversely, well-functioning families tend to foster a more positive self-view and better self-compassion. Functional family systems are associated with secure parent-child attachment (Pu & Rodriguez, 2022), which cultivates a robust sense of security (Liang et al., 2024). Secure attachment has been shown to significantly correlate with dispositional mindfulness (Yang & Oka, 2022). Children raised in environments characterized by emotional attunement, responsibility, warmth, and autonomy support are more likely to develop secure attachment and trust in interpersonal relationships (Mphaphuli, 2023), which in turn bolsters higher levels of mindfulness (Pepping et al., 2015). Furthermore, securely attached young adults tend to report greater self-compassion compared to those with anxious or avoidant attachment styles, suggesting that the roots of compassion are deeply embedded in early attachment experiences (Mackintosh et al., 2018; Neff & McGehee, 2010). Meanwhile, insecure attachment style, often rooted in avoidant or anxious parental patterns (Anikiej-Wiczenbach et al., 2024) is associated with negative self-compassion characterized by ineffective emotion regulation strategies (Hicks & Kearney, 2019).

In addition, a family environment characterized by harmony and genuine care allows individuals to experience warmth and authentic support, express themselves, and evolve a sense of emotional, mental, and physical wellness (Mphaphuli, 2023), thus contributing to the improvement of positive emotional states (Chen et al., 2023) and the capacity for emotion regulation in adverse situations (Farmakopoulou et al., 2024). In turn, emotional self-regulation can predict self-compassion (Masoumi et al., 2022). One form of emotional regulation is self-soothing during strenuous events (Gračanin et al., 2014), which constitutes a key component of self-compassion (Kirschner et al., 2019; Neff, 2003b). Moreover, self-compassion has been proposed as a psychological mechanism that may mediate the relationship between emotion regulation and mental health (Inwood & Ferrari, 2018).

Furthermore, in this study, mindfulness and self-compassion were found to be significantly and positively associated. This mechanism may be explained by the way mindfulness, which comprises non‑judgemental awareness of present experiences, increases the likelihood that painful emotions are noticed and acknowledged, thereby allowing individuals to respond with self-compassion (Svendsen et al., 2017). Svendsen and colleagues further describe this mechanism as involving attentiveness to suffering combined with an active desire to alleviate it (reflecting the dimension of self-kindness), a recognition that all people struggle at times (reflecting common humanity), and an awareness that adversity, imperfection, or failure do not define one’s worth (reflecting low over-identification). These findings suggest that mindfulness may serve as a protective mechanism, enabling individuals to respond to negative experiences with higher self-compassion.

Furthermore, the partial mediation effect of mindfulness in the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion provides important insight into the psychological processes underlying this relationship. Specifically, part of the negative impact of dysfunctional family functioning on self-compassion can be explained by the lower levels of mindfulness observed among individuals from such families. However, since the indirect effect accounted for only 42.1% of the total effect, other mediators likely play a role. Based on the synthesis of findings aforementioned, factors such as secure attachment and self-regulation appear to be potential mediators in explaining this pathway. Future research is encouraged to investigate the mediating roles of these variables in order to more comprehensively understand the mechanism linking family functioning and self-compassion.

The findings of this study have several important theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, the study highlights that mindfulness may operate through both lower levels of family dysfunction and higher levels of self-compassion. Poor family functioning predicts lower levels of mindfulness, which in turn weakens self-compassion among college students. Conversely, better family functioning predicts higher mindfulness, thereby enhancing self-compassion in this population. These findings underscore the crucial role of the family in the development of individuals’ mental capacities and in influencing how they view, perceive, and behave toward themselves and the world around them. This aligns with the Bowen family systems theory, which posits that the family is an emotional system in which members mutually influence and are influenced by one another (Bowen, 1978; Erdem & Safi, 2018). The family systems approach thus provides a valuable theoretical lens for understanding the phenomenon of family functioning (Fingerman & Bermann, 2000), and the current findings contribute to extending this framework, particularly concerning the development of individuals’ internal qualities. It is also important to acknowledge that participants in this study came from diverse family structures, including intact, divorced, and widowed families. While these structural differences may conceptually influence how individuals perceive family functioning, additional confounder analyses revealed that parental marital status did not significantly affect the structural relationships among the key study variables. Therefore, all participants were retained in the analysis to preserve statistical power and to reflect the diverse realities of family life in emerging adulthood. Practically, the results of this study offer an empirical foundation for designing mindfulness-based interventions aimed at strengthening self-compassion among college students from dysfunctional family backgrounds in higher educational settings.

This study is not without limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences between variables. Future research is recommended to employ longitudinal or experimental designs to better examine the causality of these relationships. Additionally, although this study modelled the directional pathway from family functioning to self-compassion through mindfulness, future research may also benefit from applying multi-stage models that account for potential feedback loops between variables, which may provide a more comprehensive understanding of how these psychological processes evolve over time.

Second, the data were collected through self-report measures, which are prone to perceptual bias, particularly in assessing family functioning, a construct that is inherently systemic and complex beyond individual perception. Nevertheless, this also offers an important insight: individuals’ perceptions of their family may significantly determine how their mental capacities are formed or developed. Therefore, it is essential not only to implement more comprehensive and objective assessments beyond self-report, but also to consider psychoeducational efforts regarding family functioning targeted at both students and their parents. This may be important in supporting students’ optimal functioning in higher education. Students may need to understand and redefine their family functioning more healthily and holistically, as such perceptions can influence the development of their internal capacities, especially in facing the complexities of student life and emerging adulthood. Although college students begin to establish independent lives (Akin et al., 2024), the family remains a vital contributor to their psychological well-being (Mendoza et al., 2019). Perceived positive family relationships, characterized by greater parental involvement, autonomy support, parental warmth, and lower levels of behavioural and psychological control, are associated with better psychological adjustment (Mendoza et al., 2019).

Third, although the sample included students from 15 universities, it may not be fully representative of the broader young adult population in Indonesia. The predominance of undergraduate students (92.5%) and the overrepresentation of women (62.9%) may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research is encouraged to employ more diverse sampling methods that include a more balanced gender composition and a broader range of educational levels and life circumstances.

Fourth, although it is set in an Indonesian context as a collectivist country, this study did not account for the cultural context, which limits the exploration of how family functioning, mindfulness, and self-compassion mechanisms operate across different cultural backgrounds. Akin et al. (2024) argued that cultural norms and expectations may influence the evolving parent–child relationship during emerging adulthood or college years, especially in family-oriented cultures where communal connectedness is emphasized. Beyond this, cultural values may also shape how mindfulness and self-compassion are experienced and structured. In collectivist cultures, self-compassion is often embedded in long-term orientation and emotional restraint, fostering a more integrated form of self-kindness (Montero-Marin et al., 2018), while in individualistic cultures, it may appear more fragmented due to a stronger emphasis on independence and achievement. Likewise, mindfulness may be approached as an ethical or spiritual practice in Eastern traditions, but as an individual regulation and self-improvement tool in Western contexts (Tsatsou, 2024). These cross-cultural variations underscore the importance of future research incorporating culturally sensitive frameworks to better comprehend how family functioning and these intrapersonal capacities interact within different sociocultural contexts.

Finally, while this study identified mindfulness as a partial mediator in the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion, future research may benefit from exploring potential mediating variables such as attachment style and emotion regulation, as mentioned above. In addition, investigating the effectiveness of mindfulness and self-compassion training programmes among students with varying levels of family functioning could further inform intervention strategies tailored to individual needs.

Despite its limitations, this study holds significant value in expanding the understanding of the dynamics between family functioning, mindfulness, and self-compassion among college students. By identifying mindfulness as a partial mediator, the study fills a gap in the literature concerning the psychological mechanisms that bridge relational experiences with intrapersonal capacities. These findings not only reaffirm the foundational role of the family in shaping and fostering mindfulness and self-compassion, but also pave the way for the development of mindfulness-based interventions designed to strengthen self-compassion, particularly among students from dysfunctional family.

CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated the direct and indirect effects in the relationship between family functioning, mindfulness, and self-compassion among college students. Higher level of family dysfunction is associated with lower levels of mindfulness and self-compassion, with mindfulness partially mediating the relationship between family functioning and self-compassion. These results broaden our understanding of how early relational experiences – especially within the family – affect students’ ability to remain present with non‑judgemental awareness and cultivate compassion toward themselves. Based on the findings, the develop-ment of mindfulness-based self-compassion interventions for students from dysfunctional family backgrounds is strongly recommended in higher education settings. Future research is also encouraged to implement longitudinal or experimental designs to better examine the causality of these relationships, apply multi-stage models that account for potential feedback loops between variables, employ more diverse sampling methods that include a more balanced demographic characteristics composition, explore other potential mediators, and incorporate cultural dimensions to deepen cross-contextual understanding of these psychological mechanisms.