BACKGROUND

Disparities in healthcare, particularly in pain management, remain a pervasive issue despite increasing efforts to address inequities in clinical practice. Research has consistently demonstrated that racial and gender biases influence clinical decision-making, often leading to the unequal treatment of systematically marginalized patients (Mende-Siedlecki et al., 2021; Schäfer et al., 2016). For example, Black, Latine, and Asian patients are less likely to receive adequate pain management compared to their White counterparts, even when presenting with similar symptoms (Bonham, 2001; Drwecki et al., 2011; Green et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2024; Lloyd et al., 2022; Mende-Siedlecki et al., 2021; Mossey, 2011; Ng et al., 1996a, b; Pletcher et al., 2008). Gender disparities also exist, as women are less likely to receive pain medication and experience longer wait times than men (Chen et al., 2008; Schäfer et al., 2016). These differences are likely due to women’s pain being taken less seriously than men’s pain because of stereotypes of women being emotional and dramatic (Schilter et al., 2024).There is a lack of research, however, on pain management including the intersection of race and gender. Some research suggests that patients with compounding intersectional identities, such as middle-aged and older Black women, experience a high risk of pain and pain-related disabilities (Walker Taylor et al., 2018). Further, transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) patients have not been included in pain management research, despite TGD patients experiencing inadequate healthcare (Safer et al., 2016) and their pain not being taken as seriously as cisgender patients due to damaging societal stereotypes about TGD people being untrustworthy and mentally ill (Paganini et al., 2025). The current study contributes to the growing body of research investigating the intersection of race, gender, and explicit biases in shaping pain management decisions.

Modern racism has been identified as one mechanism responsible for racial disparities (Fiscella et al., 2021; Waytz et al., 2015) and is characterized by endorsement of the following beliefs: (1) discrimination is no longer a problem for Black people; (2) Black people persist in making unreasonable demands for changes to the status quo despite already having sufficient rights; and (3) the support Black people receive from the government and other institutions is unwarranted and amounts to “preferential treatment.” To measure this form of racism, McConahay developed the Modern Racism Scale (MRS; McConahay, 1986). Though the Modern Racism Scale was created decades ago, scores on the Modern Racism Scale predict current attitudes about racial issues. For example, those higher in modern racism showed less support for the Black Lives Matter protests (Miller et al., 2021). Regarding pain management, one study found that as participants’ modern racism increased, they rated Black people’s pain as less intense compared to White people’s pain (Dildine et al., 2023). Given the nature of the Modern Racism Scale, however, it is also plausible that those high in modern racism might believe that marginalized groups, including Black patients, do not deserve “special treatment” in healthcare and thus rate their pain as similar to other patients. Those lower in modern racism, on the other hand, might be more aware of systemic racial inequities and overcompensate (Monteith et al., 2015), giving more pain medication to Black individuals than other groups.

However, focusing solely on Black patients may overlook the broader implications of explicit biases for other racial and ethnic groups. Research indicates that Latine and Asian patients also face unique challenges in healthcare settings, including stereotypes that downplay their pain experiences or incorrectly frame them as “model minorities” (Chen et al., 2016; Jimenez et al., 2014). Thus, while modern racism remains the primary focus of the current work, examining pain management for Latine and Asian patients enables a more comprehensive understanding of how racial biases intersect with pain care inequities and decenters whiteness as the only comparison group (Garay & Remedios, 2021).

A potential important moderator of race and gender biases in pain care is the decision-makers’ (i.e., providers in healthcare or participants in research studies) own race or gender, due to socialization differences (Ng et al., 2019). For example, White men exhibit higher levels of explicit modern racism compared to women (Schuman et al., 1997). This may stem, in part, from broader societal norms that have historically granted greater privilege to White men, fostering less of a prosocial orientation, less awareness of systemic inequities, and greater resistance to acknowledging racial bias (DiAngelo, 2020; Johnson & Marini, 1998). Furthermore, White men often occupy positions of power within healthcare and other institutions, potentially perpetuating disparities (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014). These factors emphasize the importance of investigating how participant identities interact with patient identities to influence clinical decisions.

Thus, the present study investigates whether participants’ modern racism and identity influences pain management decisions for hypothetical patients varying in race and gender. We hypothesized that participants high in modern racism would either 1) demonstrate a racial bias whereby they provided less pain management to Black patients compared to other patients, especially White patients (Dildine et al., 2023; Mende-Siedlecki et al., 2021), or 2) they would demonstrate a “one-size-fits-all” approach to pain management, treating all patients similarly due to their reliance on beliefs that all people, regardless of their race, should be treated the same (Mende-Siedlecki et al., 2021). We also hypothesized that those low in modern racism would be more aware of systemic racial inequities and provide more pain management to Black patients compared to other patients (Monteith et al., 2015). We exploratorily examined how participants’ own gender and race moderated the effect of modern racism on pain management decisions.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

Participants (N = 780) from the United States were recruited from Prolific (an online participant recruitment platform) for a 30-minute study in which they were compensated $6. Participants were purposively sampled across four groups: White cisgender people (n = 195), White gender diverse people (n = 195), cisgender people of color (n = 195), and gender diverse people of color (n = 195). Participants were excluded for failing two attention checks (n = 20), for a final sample of N = 762 participants (Mage = 34.24, SDage = 11.90; see Table 1 for participant demographic information). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Rhode Island.

Table 1

Demographic information of participants (N = 762)

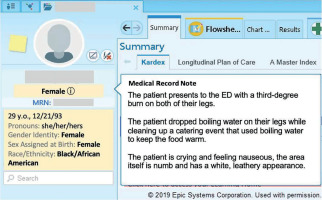

Upon providing informed consent, participants were presented with 20 different acute pain vignettes in an electronic medical record form. For each vignette, a hypothetical patient’s gender (cisgender man, cisgender woman, transgender man, transgender woman, and nonbinary) and race (White, Black, Asian, Hispanic) were randomly assigned (see Figure 1 for an example of how vignettes were presented to participants). Each possible combination of patient race and gender was presented only once, and each pain scenario was presented only once, in random order. After reviewing the medical record vignettes, participants rated each patient’s pain, the urgency of their need for medication, and the amount of medication they should receive, and self-reported their own demographic information and their own modern racism (McConahay, 1986).

MEASURES

Medical record pain vignette. Vignettes were produced by the researchers and were fictional accounts of patients experiencing acute pain from an injury and presenting to the emergency department. We used a photograph of a sample Epic Systems electronic health record software and overlayed textboxes to alter gender, race, and pain information. Nine research assistants rated each pain scenario (without any gender or race information) as normal (within +/– 3 SDs) in terms of severity (α = .95) and typicality (α = .78).

Pain management ratings. After reading each vignette, participants rated each hypothetical patient on the following dimensions: “How much pain is this patient experiencing?” (0 – no pain at all to 10 – worst pain possible), “Rate the urgency of this patient’s need for pain medication” (0 – not urgent at all to 10 – extremely urgent), and “How much pain medication should the patient receive?” (0 – minimal amount to 10 – large amount). These three items were combined into a pain management composite (α = .93).

Modern racism. The Modern Racism Scale (MRS; McConahay, 1986) is a seven-item scale designed to measure individuals’ modern racism. One example item is “Discrimination against Black people is no longer a problem in the US” (α = .91). Responses to these statements were anchored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score on the scale indicates higher modern racism. We modified the language in the scale to be person-centered (i.e., “Blacks” was changed to “Black people”).

POWER ANALYSIS

An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power (Version 3.1; Faul et al., 2009) to determine the required sample size for detecting a small effect size (f = 0.10) with an alpha level of 0.05 and a desired power of 0.80 for the most complex model that we ran, a 4 (patient race: White, Black, Latine, Asian) × 5 (patient gender: cisgender man, cisgender woman, transgender woman, transgender man, nonbinary person) × 3 (participant gender: cisgender man, cisgender woman, gender diverse person) × 2 (participant race: White vs. person of color) factorial ANOVA. The analysis indicated that a sample size of 204 participants would be necessary to achieve adequate power; thus, we were adequately powered to detect small effects.

DATA ANALYSIS

To examine differences in pain management for patients varying in race and gender, we performed a median split on modern racism, classifying participants into ‘high’ and ‘low’ groups based on whether their total Modern Racism Scale scores fell below or above the sample median (Mdn = 1.14). This categorical grouping enabled comparison of mean pain management scores across levels of modern racism while also taking into account patient race and gender.

Hypothetical patient race (White, Black, Latine, Asian) and gender (cisgender man, cisgender woman, nonbinary person, transgender man, transgender woman) were entered into the general linear model as within-subjects variables, while modern racism (high vs. low) was entered as a between-subjects variable. The dependent variable was the pain management composite. Thus, a 4 (patient race: White, Black, Latine, Asian) × 5 (patient gender: cisgender man, cisgender woman, nonbinary person, transgender man, transgender woman) × 2 (participant modern racism: high vs. low) factorial ANOVA was used to answer our primary research question. We conducted a separate factorial ANOVA where we added participant race (White vs. people of color) and participant gender (cisgender men, cisgender women, gender diverse individuals) as between-subjects variables and patient race (White, Black, Latine, Asian) and patient gender (cisgender man, cisgender woman, nonbinary person, transgender man, transgender woman) with the pain management composite as the dependent variable. We report partial eta squared (η2p) as a measure of effect size of omnibus tests with small effects η2p = .01, medium effects η2p = .06, and large effects η2p = .14. For pairwise comparisons, we report Cohen’s d with small effects d = .20, medium effects d = .5 and large effects d ≥ .80.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics on each of the pain management items and correlations with modern racism are presented in Table 2. Across all hypothetical patient vignettes, participants higher in modern racism compared to those lower in modern racism assessed the patient as in less pain, rated the patient as less urgently needing pain medication, and recommended less pain medication.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and correlations between modern racism and pain item ratings

| Item/Scale | M (SD) | Modern racism |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pain Item 1 | 7.32 (1.12) | –.15** |

| 2. Pain Item 2 | 7.17 (1.38) | –.17** |

| 3. Pain Item 3 | 6.51 (1.61) | –.10* |

| Pain Management Composite | 7.00 (1.29) | –.14** |

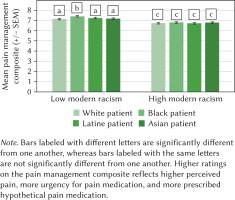

The 4 (patient race: White, Black, Latine, Asian) × 5 (patient gender: cisgender man, cisgender woman, nonbinary person, transgender man, transgender woman) × 2 (participant modern racism: high vs. low) factorial ANOVA revealed a small main effect of modern racism such that those high in modern racism provided overall less pain management than those low in modern racism (F(1, 729) = 25.58, p < .001, η2p = .03). This was qualified by a significant interaction between patient race and participant modern racism (F(3, 2187) = 2.69, p = .045, η2p = .004) (Table 3; Figure 2). Specifically, among participants low in modern racism, Black patients (M = 7.39, SD = 1.30) received significantly more pain management compared to White (M = 7.13, SD = .1.34, d = .26), Asian (M = 7.18, SD = 1.34, d = .21), and Latine patients (M = 7.23, SD = 1.34, d = .16) (ps < .007, all small effects). Among participants high in modern racism, there were no significant differences in pain management according to patient race (ps > .117) (Table 4).

Table 3

Factorial ANOVA results for pain management composite by patient race, patient gender, and participant modern racism (high vs. low)

Table 4

Means and standard deviations for pain management composite by patient race, patient gender, and participant modern racism (low vs. high)

Figure 2

Bar graph showing the average pain management composite ratings for White, Black, Latine, and Asian patients stratified by low vs. high Modern Racism Scale (MRS) score

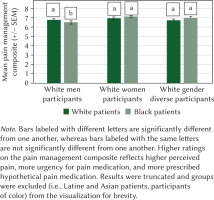

A second factorial ANOVA was run, which included participant race (person of color, White), participant gender (cisgender man, cisgender woman, gender diverse), patient race (White, Black, Latine, Asian), and patient gender (cisgender man, cisgender woman, nonbinary person, transgender man, transgender woman). Of note is the significant three-way interaction of patient race, participant gender, and participant race (F(6, 2115) = 2.85, p = .009, η2p = .008) (Figure 3). Among White participants rating Black patients, men provided less pain management (M = 6.50, SE = .16) than women (M = 7.14, SE = .13) and gender diverse participants (M = 7.03, SE = .12) (pairwise ps < .008). However, no differences existed when White participants were rating White patients (pairwise ps > .193). For participants of color, there were largely no significant participant gender differences according to race of the patient, except that gender diverse participants (M = 7.21, SE = .12) provided more pain management to Latine patients than men participants (M = 6.76, SE = .14) (p =. 017).

Figure 3

Bar graph showing the average pain management composite ratings for White and Black patients stratified by participant gender (cisgender man, cisgender woman, gender diverse)

To exploratorily examine the differential pain management among White participants, we compared racism levels among White cisgender men, White cisgender women, and White gender nonconforming individuals. A one-way ANOVA revealed that among White participants, men were highest in modern racism (M = 2.05, SD = 1.03), followed by women (M = 1.65, SD = 0.81), and then gender diverse individuals (M = 1.18, SD = 0.43) (F(2, 367) = 38.99, p < .001, η2p = .18). All groups were significantly different from one another (ps < .001).

DISCUSSION

Participants with low modern racism provided more pain management to Black patients compared to other groups, and those high in modern racism provided similar pain management to all racial groups, though all pairwise comparisons showed only small differences. Those high in modern racism also tended to prescribe less pain medication overall. We expand on the pain disparities literature by understanding how modern racism might affect pain management of different racial/ethnic and gender groups. Though we did not find any significant effects according to patient gender, it is still important to include gender, given the intersectional nature of documented pain disparities.

Participants low in modern racism recommended more pain management to Black participants compared to other groups and did not perpetuate the well-known pain disparities (i.e., that Black patients receive less pain management than other groups). These findings align with those of Wong et al. (2024), who found that Black emergency department patients were prescribed more non-opioid pain medications than White individuals. Consistent with the aversive racism framework, participants will generally not express racism when their behaviors can be perceived as obviously racist, or they might even overcorrect (e.g., in the legal setting, showing leniency toward a Black defendant compared to a White defendant; Bucolo & Cohn, 2010; Cohn et al., 2009). It is possible in our study that participants low in modern racism were particularly attuned to the purpose of the study when reading vignettes of patients of multiple races and therefore sought to reduce inequities (i.e., providing more pain management to Black patients than other groups). Participant modern racism seems to be a critical moderator of this effect, as those high in modern racism were affected differently by the explicit nature of the task in that they did not provide more pain management to Black patients compared to other groups. Specifically, participants low in modern racism appeared motivated to engage in anti-racist behavior, while those high in modern racism applied a “one size fits all approach” to pain management, directly reflecting more endorsement of items in the Modern Racism Scale, such as “Discrimination against Black people is no longer a problem in the United States” and “Over the past few years, the government and news media have shown more respect to Black people than they deserve.”

While on the surface it may seem beneficial that participants high in modern racism provided a one size fits all approach to pain management regardless of patient race, behaviors that ignore racial disparities are harmful in that they can lead to negative consequences such as less cultural competency, less detection of overt racism, and less anti-racist behavior in a variety of settings (Apfelbaum et al., 2010; Yi et al., 2023). Those low in modern racism showed a different strategy in pain management, providing more pain management to Black patients compared to other patients. This strategy is also problematic, as illustrated by the overprescribing of pain medication to certain groups, which led to inequities in the opioid crisis (Flores et al., 2023; Rummans et al., 2018). The most effective strategy for pain management is an individualized, patient-centered approach that considers race and gender without relying on stereotypes. This approach prioritizes cultural humility, shared decision-making, and evidence-based practices, ensuring that care is tailored to the patient’s unique experiences and social context. In clinical practice, this might involve explicitly asking about patients’ prior experiences with pain treatment, considering how experiences of discrimination and systemic racism and sexism may affect trust and communication, and collaboratively discussing treatment options that align with the patient’s values and concerns. By addressing race and gender biases and acknowledging social determinants of health, this strategy fosters equitable care while avoiding harmful generalizations or perpetuating disparities in pain management (Lekas et al., 2020).

Pain management strategies also differed according to participant gender. White men provided less pain management to Black individuals than White women or White gender diverse individuals. This difference did not emerge among participants of color. With further investigation, we identified that White men had the highest levels of modern racism, which perhaps explained why they provided less pain management to Black patients than other patients.

One limitation of this study is the explicit nature of the scale used to assess modern racism, the Modern Racism Scale, which may have heightened self-presentational concerns about appearing prejudiced, and lessened the likelihood that participants revealed their “true” racial attitudes. Thus, these effects might be even stronger than presented in the current work. Future researchers should attempt to replicate these findings with a more recent racism scale, as the Modern Racism Scale was developed in 1986, and race relations have changed since then. Though the within-subject design is generalizable to real life medical situations (i.e., clinicians care for multiple patients sequentially), this might have also heightened the salience of racial and gender differences between patients and revealed the purpose of the study, which may have reduced biased responding for patients of color, again underestimating the extent of pain management biases. In addition, though the vignettes were modeled after previous research (Hirsh et al., 2009), it would have been advantageous for experts in the medical field to give feedback on the vignettes to make them more generalizable to real-life medical emergencies. Future researchers should also consider observing other pain management outcomes, such as referrals to other healthcare providers (e.g., psychologists).

CONCLUSIONS

We found that modern racism affects pain management of patients, in that those high in modern racism seem to ignore experiences of pain and health disparities among people of color, while those low in modern racism seem to provide more pain management to Black patients than all other patients. Participant gender also played a role in that White men provided less pain management than White women and White gender diverse participants when rating Black patients. Medical educators should educate their trainees about health disparities as a consequence of structural inequities and intervene and give feedback when they observe racism in pain care interactions.