BACKGROUND

The livelihoods and professional careers of individuals have been significantly threatened by the recent global pandemic. Organizational life has been profoundly affected and irreversibly changed as a result. Long-lasting impacts on the economy and business mean that both individuals and whole organizations need to navigate ‘new normal’ ways of working, adapting to new challenges as they go. Remote working with the use of digital technologies has been a new norm. With some employees being furloughed, some working remotely, and some having to perform increasing caring responsibilities at home (such as home-schooling), their lives are becoming more complex, hectic, uncertain and unpredictable.

The CIPD (Chartered Institute of Personnel Development) building on the Good Work Index has tracked mental and physical workplace health since 2018, revealing “a steady decline. This trend has continued through the pandemic, and it seems COVID-19 is having a direct impact on mental and physical health: around four in ten workers say their mental and physical health has worsened since the pandemic” (Williams et al., 2020, p. 53).

In the light of the above findings, with consequent long-term job insecurity and general decreasing wellbeing levels in organizations, concepts such as lack of control over work, company’s climate and organizational citizenship behaviors attain undeniable prominence.

Working excessively has two faces. On the one hand, it involves engagement, passion, authentic commitment and a genuine desire to ‘walk an extra mile’ beyond what is required. This can be a manifestation of internal drive when employees recognize the benefits of working hard, seeing it as an opportunity for personal growth, source of life satisfaction and sense of achievement. On the other hand, when excessive work is driven by inner compulsion, provides tension-releasing benefits and is carried out beyond financial and organizational requirements, it can become an addiction, known as workaholism (Mazzetti et al., 2014).

The attitude of overwork can also be triggered by the organizational environment, which fosters employees’ additional involvement and extra efforts. Thus, the motives for making above-average commitments at work are not always clear-cut. However, regardless of the motives, an extra dedication to work can lead to a serious imbalance between work and non-professional life, health and well-being decline as well as decreased performance (Mazzetti et al., 2014). Although the dual nature of working excessively (i.e. opposing phenomena of healthy engagement versus workaholism) has been investigated (Van Wijhe et al., 2011), there is still little research showing the mechanisms underlying this ambivalence. The purpose of this study is to contribute to bridging this gap.

LACK OF CONTROL OVER WORK AND OVERWORK CLIMATE

The factors contributing to the lack of control over work can stem from the external work environment, internal characteristics of the actor, or the job itself. Lack of control over work has clear psychosocial cognitive, emotional and behavioral symptoms. Behaviorally, it manifests as working excessively long hours while neglecting other areas of social/family functioning at the same time. Emotionally, it is manifested as an irresistible internal compulsion to work with the painful awareness of not fulfilling external demands and resulting in family-work related conflicts. Cognitively, it is an inability to distance oneself from work, ruminating over work-related issues, even if one eventually takes some time off (Paluchowski et al., 2013).

Nowadays, a growing number of employees have the opportunity to decide about their working hours (Costa et al., 2006). Additionally, making use of information and communication technologies such as the Internet, cell phones and laptops enables employees to work outside of the usual spatial and temporal office framework (Day et al., 2019). A continuously increasing proportion of telework in the total volume of employee responsibilities is observed (Bae et al., 2019). In addition, the currently designed work processes in many occupations mean that work is never completely finished at the end of the day. Paradoxically, the greater flexibility of work makes it easier for an employee to lose control over it. Apparent freedom resulting from working from home and self-management with no clear boundaries can potentially mean losing control over work. Pérez-Zapata (2020) calls this the “autonomy paradox” and highlights it as being a double-edged sword. On one hand it may promote health, while on the other it may lead to overwork and workaholism when one internalizes over-demanding workloads. Consequently, in the face of ever-growing work intensification, setting boundaries and maintaining a work-life balance is becoming a growing challenge. This is also visible in the context of employees’ health (Arvola & Kristjuhan, 2015). Lack of control over work can be considered as a consequence of excessive workload, which is most commonly related to work addiction. Individuals who have lost control over work are aware that their full dedication to work is associated with extremely limited social and family life (Paluchowski et al., 2014) and deterioration of health (Ferrand et al., 2017).

However, potentially losing control over work and risking becoming a workaholic can be related to specific job characteristics and also temperamental traits (Paluchowski et al., 2013). In helping professions, when a major driver for work is the mission to help others, individuals are ready to self-sacrifice and commit to above-average engagement in order to fulfil their strong sense of social vocation. It is a ‘higher purpose’ that justifies excessive hours and devotion. Moreover, when this is the case, there may be no apparent family-work conflict as the family seems to be sympathetic and understanding of the higher purpose and thus offer their full support for the mission.

An additional factor adding to a not so ‘cut and dry’ understanding of lack of control over work is the fact that losing control over work may potentially present some secondary benefits for the actor, and thus be psychologically rewarding. Apart from its tension-releasing property, working excessively provides the ability to perceive oneself as competent, efficient and effective. It can perpetuate one’s high self-esteem (Paluchowski et al., 2013), which is an important factor in today’s world where career-related and social competition and comparisons are so pervasive.

Apart from the internal factors contributing to one’s lack of control over work delineated above, some of the additional factors are external, namely the overwork climate which permeates the organization. Organizational psychological climate is a “cognitively based description of the work environment” (Kopelman et al., 1990, p. 295). It serves as a basis of interpretation, but even more important in the context of behaviors, it is a guide to action. “Climate is a sense of imperative” (Kopelman et al., 1990, p. 296) derived from the employees’ shared perceptions and meanings of organizational processes, procedures, policies, practices, routines and rewards they observe and subjectively experience. As a construct, organizational climate is not a direct reflection of what an organization is. It is an interplay of the environment characteristics and employees’ responses to it. Thus, if the work environment is characterized by a high level of time and work-load pressures, it will encourage some employees to make more work-related efforts and foster workaholic tendencies (Mazzetti et al., 2014).

Overwork climate is defined as “employees’ perceptions of a work environment that requires them to work overtime and at the same time, does not allocate any rewards for this extra effort” (Mazzetti et al., 2016, p. 881). Employees stay at work late only to follow the implicit behavioral rules that exist in the organization. Staying after hours becomes a practice and takes up much of the employees’ free time. This, in turn, significantly interferes with their household duties, and hinders building satisfying relationships with family and friends. Therefore, we predict that overwork climate and lack of control over work have a common variance and that they are positively correlated (hypothesis 1). This does not mean that the lack of control over work arises only from working conditions that employees perceive as pressurizing. As we mentioned above, some people identify with work above the norm, and treat it as a central and integral value in their life. Employees from both groups take on a heavy workload and may find it difficult to perform well in both professional and non-professional roles.

LACK OF CONTROL OVER WORK AND OCB

Lack of control over work – regardless of whether it is conditioned by an overwork climate or one’s value system – can be conducive to an employee taking on an increasing number of responsibilities. They tend to engage in multiple projects and tasks outside of their job remit and working time framework. These ‘beyond one’s duties’ activities are referred to as organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). OCB refers to the actions and behaviors that are not officially required from employees. Defined as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and in the aggregate promotes the efficient and effective functioning of the organization” (Organ et al., 2006, p. 43), they are not critical to the performance of tasks assigned to a given job position, but they bring benefits to the team and contribute to improving the organizational functioning and efficiency (Organ & Ryan, 1995; Podsakoff et al., 2000). After analyzing publications on OCB, Podsakoff et al. (2000) list the most prevalent classes of behaviors that constitute this phenomenon: helping others, perseverance, organizational loyalty, organizational obedience, initiative, civil virtue, and self-development. Employees’ manifestation of OCBs means they are ‘giving their all’. They consider their work to be much more than a formal contract would suggest. Even if it means significant overtime work, they will strive to do their best to ramp up ever-increasing pace and growth in their teams or organizations efficiency. That is why we anticipate that employees who are higher on the scale of lack of control over work have a stronger tendency towards organizational citizenship behavior (hypothesis 2).

While a plethora of research has underlined the positive aspect of OCB for an actor and their team, there is a disproportionally small, but continuously growing area of research examining the ‘dark side’ of OCBs (Koopman et al., 2016). The results of a study published by Becton et al. (2007) showed that in organizations where OCBs are formally required by supervisors, by extending the criteria of performance appraisals and job reviews, they change their character. Under these conditions, OCB can contribute to employees experiencing job-related stress and work-life balance issues (see also Bolino & Turnley, 2005) as well as emotional exhaustion caused by providing continuous assistance and support for others (Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2015). While helping others usually increases the level of positive affect by making ‘helpers’ feel good, in the long run it may result in significant trade-offs with task-related activities (Barnes et al., 2008) as well as impairing progress towards goals (Bergeron, 2007). One of its further downsides may be the tendency to foster work-family conflict due to depletion of resources (time and energy) (Gutek et al., 1991).

How employees perceive their own behaviors depends on their motives: the employee’s proactive behaviors, when performed to manage impression (IM – impression management motive) may lead to citizenship fatigue (Qiu et al., 2020). If the OCBs are performed out of authentic dedication and concern for the company (OC – organizational concern motive) it may lead to enhanced performance and employees thriving at work (Qiu et al., 2020). However, when OCBs are performed to comply with the management explicit or implicit expectations of overwork, they are no longer an accurate indicator of authentic work commitment. They become ‘mandatory’ and can hardly be called ‘citizenship’.

In the face of these findings, the magnitude of the correlation between lack of control over work and OCB will be related to the source of variance of this first variable. If the triggering factor for lack of control over work is a demanding work environment characterized by high overwork climate, then lack of control over work will contain irrelevant predictive variance for measuring OCB.

OVERWORK CLIMATE AS A SUPPRESSOR IN THE LACK OF CONTROL OVER WORK AND OCB RELATIONSHIP

Horst (1941) explained that most predictors had components that were both related and unrelated to the outcome variable. Therefore, it is very useful to identify suppressor variables that contribute to explicating the meaning of outcome variable by highlighting opposing elements. Suppressor effects are defined as cases in which the inclusion of a second predictor increases the predictive power of one or both predictors (Cohen & Cohen, 1975; Paulhus et al., 2004). The suppressor variable removes irrelevant predictive variance from the other predictor and increases the predictor’s regression weight, thus increasing overall model predictability (Pandey & Elliott, 2010).

Based on the previous considerations, we expect that overwork climate is a suppressor variable in the relationship between lack of control over work and OCB (hypothesis 3).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

Data were collected through online questionnaires in a cross-sectional study. When recruiting participants for the study, the criterion of seniority for a minimum of 6 months in the current organization, at the current job position, was applied. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. The total of 580 employees (including 355 women, i.e. 61%) were between 18 and 66 years old (M = 33.15, SD = 12.11) and had an average seniority of M = 12.00 years (SD = 11.01). Participants were employees working in a variety of areas: production (19%), sales and customer service (35%), organizational support (e.g. administration, HR, accounting, legal department; 20%), and services in the public sector (e.g. doctor, nurse, teacher, soldier, fireman; 26%). The sample comprised 16% managers and 84% employees in non-managerial positions. The group consisted of employees of micro (less than 10 employees; 20%), small (from 10 to 49 employees; 26%), medium-sized (from 50 to 249 employees; 24%), and large organizations (at least 250 employees; 30%). As for educational level, 8.3% had primary education, 46.3% had completed high school, and 45.4% were university graduates.

MEASURES

The measures included self-reports from questionnaires on: (a) overwork climate, (b) lack of control over work, and (c) organizational citizenship behavior.

Overwork climate. The Overwork Climate Scale (OCS) developed by Mazzetti et al. (2016), in the Polish adaptation by Piotrowski and Jurek (2019), was used in this study. It consisted of 11 items that are answered using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The dimensions contained in the instrument were overwork endorsement (example item: “Almost everybody expects employees to perform overtime work”) and lacking overwork rewards (example item: “Overtime work is fairly compensated by extra time off work or by other perks” – reverse coded).

Lack of control over work. This variable was measured using the Working Excessively Questionnaire (WEQ) developed by Paluchowski et al. (2014). The lack of control over work scale consists of 16 items (e.g. “Even when I’m not working, I think about work-related issues”) that are answered using a Likert scale with five responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Organizational citizenship behavior. In the current study four items from Lee and Allen (2002) describing behaviors indicating organizational citizenship behaviors directed towards the organization (e.g. “Take action to protect the organization from potential problems”) were used. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The results of the reliability analysis of all scales used in the current study are presented in the Results section.

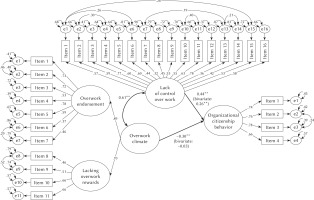

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To test our hypotheses, we used structural equation modelling (SEM) with robust maximum likelihood estimation. SEM utilizes a confirmatory approach in order to examine the structural relations between variables using theory to shape models that attempt to explain variance in the data. We used the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) in the R environment (R Core Team, 2019) for calculations. In the model, all variables were treated as latent variables reflecting their indicators (items or other latent variables). To assess model fit, we examined the χ2 statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). We applied the commonly used cut-off criteria of these indices to assess model fit (i.e. CFI > .90 and RMSEA < .08 to indicate acceptable fit; e.g. Kline, 2016). The suppressor effect of overwork climate was analyzed by investigating the regression coefficients of the outcome variable (OCB) and two predictor variables (overwork climate and lack of control over work) in the models in which these predictors were applied one at a time and in the model in which they were tested simultaneously.

RESULTS

Table 1 reports the means, standard deviations, Pearson’s zero-order intercorrelations, and reliabilities (on the diagonal) of the variables under study. As seen in Table 1, overwork climate was positively related to lack of control over work, but there was no significant correlation between overwork climate and organizational citizenship behavior. Furthermore, lack of control over work was significantly positively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior.

Table 1

Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among study variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overwork climate | 2.76 | 0.83 | (.82) | ||

| 2. Lack of control over work | 2.48 | 0.75 | .45** | (.88) | |

| 3. Organizational citizenship behavior | 3.16 | 0.95 | –.07 | .26** | (.83) |

The results of the model covering the anticipated relationships between variables under study are shown in Figure 1. The tested model showed a good fit to the data with χ2 = 109.23, df = 419, p < .01, CFI = 0.90, and RMSEA = 0.050, SEMR = 0.067. Although overwork climate and OCB have a zero correlation, the prediction in OCB increases when overwork climate is added to the structural model. The reason is that overwork climate as a suppressor variable is correlated with lack of control over work (β = .61, p < .01), i.e. a predictor that is correlated with the outcome variable (OCB). When overwork climate is present, the regression coefficient describing the relationship between lack of control over work and OCB (β = .44, p < .01) is larger than its respective bivariate correlation (β = .25, p < .01). Hence, a zero-order correlation coefficient between lack of control over work and OCB does not reflect the true relationship. The suppressor variable (overwork climate) removes irrelevant predictive variance from the lack of control over work and increases the predictor’s regression weight, thus increasing overall model predictability. Moreover, overwork climate received nonzero regression weight with a negative sign in predicting OCB (β = –.30, p < .01).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Our study confirms that the stronger the overwork climate, the stronger the lack of control over work. Further, lack of control over work as a single predictor had a positive effect on OCB. And finally, we found the suppressor effect of overwork climate in the relationship between lack of control over work and OCB. Including the overwork climate in the model makes lack of control over work a stronger predictor of OCB. Using overwork climate as a suppressor variable in our study yielded two main benefits: (a) determining more accurate regression coefficients associated with lack of control over work in predicting OCB and improving overall predictive power of the model; and (b) enhancing accuracy of theory building about the role that lack of control over work plays in shaping employee organizational behavior.

The practical relevance of suppressor variables lies in their ability to increase the predictive power of another variable. Including overwork climate in the model makes it possible to suppress the irrelevant components of the lack of control over work in predicting OCB. In our study, we demonstrate that lack of control over work experienced by employees in the organization and their OCBs contain both (a) a shared ‘dedication to work’ component that creates a positive association between these two variables and (b) an unshared ‘attitude’ component that produces a natural negative correlation between these two variables (i.e. lack of control over work contains a negative attitude towards overwork climate, while OCBs are more related to organizational commitment, work engagement and generally positive evaluation of working conditions).

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Suppressor effects are difficult to interpret (e.g. the mechanism underlying suppressor variables is solely statistical – no causal intervention is assumed to produce the suppressor), are of uncertain practical value, and very often fail to replicate across samples (see Lynam et al., 2006). Ghiselli (1972) described suppressors as ‘fragile and elusive’. Concerns accompanying suppression should not discourage further research in this area. However, in order to fully confirm these research findings, the replication of suppressor effects is necessary.